The U.S. Sailboat Show in Annapolis, Maryland, held annually in October, exhibits more multihulls than any other American boat show. Many are built in Europe, but the number in this country has increased dramatically during the last decade.

The Maine Cat 30 stands out from the crowd in several ways, the most obvious of which is its open bridge deck. “Why,” one might wonder, “would a boatbuilder in Maine forsake the usually monstrous bridge deck cabin seen on other cruising catamarans?” The builder, Dick Vermeulen, has the answers.

To find our own answers, we test sailed the boat—Dr. Rob Malin’s hull #7, which he keeps in Cotuit, Massachusetts.

Design

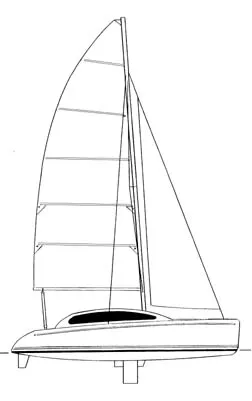

Designed by Dick Vermuelen, with line fairing assistance from George Dixon at Aerohydra in Southwest Harbor, Maine, the Maine Cat 30 was conceived to provide better performance than cats with tall, heavy bridge deck cabins; those suffer from the added weight and windage. Also, if the designer tries to lower the cabin, he may be forced to drop the bridge deck to make sufficient headroom, but then runs the risk of wave slap on the underside of the bridge deck.

The same sort of compromises are evident in the Maine Cat, except that the hardtop dodger weighs less, isn’t quite as bulky looking, and with the acrylic windows removed has less windage.

The “original” hardtop is a molded fiberglass unit that includes the supports. Later, the “sport” version was developed in which only the top is molded, and is supported by anodized aluminum tubes. With either, the entire bridge deck (cockpit) can be fully enclosed with 40-mil roll-down acrylic windows.

Our first impression was that this 8′ by 11′ area wouldn’t be as cozy as a conventional cabin, that it would be breezy and cold, making the Maine Cat suitable only for warm weather cruising. “The perfect boat for the Florida Keys and Bahamas,” we thought.

During our test sail in cool autumn weather, however, it is evident that when fully enclosed, the bridge deck area is quite snug. Not as cozy as a conventional cabin with lots of cushions and wood trim, but certainly not cold. Indeed, the windows admit a lot of sun, making it a virtual solarium.

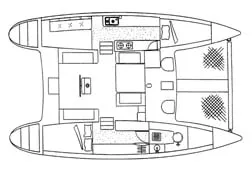

The bridge deck has a custom molded steering pedestal aft, two settee seats port and starboard, and forward a convertible dinette (LPG tank under port seat) and molded-in steps to facilitate stepping out of the bridge deck cockpit onto the forward deck.

The permanent sleeping berths, galley and nav station are situated in the port and starboard amas.

Vermeulen describes the ama design by noting their 10:1 length-to-beam ratio, fine entry and generous flare, the latter to reduce spray and to increase room below. The amas have a V-shape forward and semi-circular shapes amidships. A lot of attention was paid to the prismatic coefficients of the amas to keep the bows from burying, but at the same time give them a reasonable entry.

Unlike most cruising catamarans (The Gemini is an exception, with twin centerboards), which rely on stub keels to provide lift and reduce leeway, the Maine Cat has a single daggerboard in the starboard ama. While more expensive to build, and running the risk of damage in a grounding, we think some sort of retractable board is well worth the trouble, giving as it does superior windward sailing performance.

Twin balanced spade rudders do the steering via a custom Edson system that utilizes a rack and pinion gear and solid linkages from the pedestal to each rudderstock. On a monohull, such a system doesn’t provide feedback like a cable-quadrant steering, but on a multihull, which has precious little helm or feel anyway, the Maine Cat system is plenty sensitive and less prone to failure than cable steering.

The ama sterns each have molded steps for access to and from a dinghy. The starboard side has a freshwater showerhead.

Construction

The Maine Cat 30 is built of fiberglass with polyester resin and cored with Core-Cell structural linear foam. The lamination schedule is comprised of 1-1/2-oz. mat, two plies of 1605 bi-directional glass with 1/2-oz. mat and .9-oz. mat in each skin. Vermeulen used Core-Cell to build the prototype and tooling. Half-inch A500 Core-Cell is vacuum-bagged with the fiberglass skins to mold all components, including the amas, bridge deck, even interior cabinetry. This makes for lightweight, stiff structures, and also provides some insulating qualities against noise and condensation. Gelcoat is 944 Cook Composites.

A small amount of wood trim is used for handholds and drawers. Several woods are available; our test boat had maple. While the cabins look like the proverbial insides of a refrigerator, they are at the least utilitarian: By removing cushions and personal effects, one could practically hose down the boat inside and out.

The hull-deck joint is entirely glassed over with tri-directional fabric. There is no rubrail to conceal the joint as on conventional boats but is finely finished and impossible to detect on the outside and just barely noticeable on the inside. Vermuelen says its a $5,000 operation, but key to the boat’s clean looks.

In the bow of each ama is a collision bulkhead. These form two flotation chambers that, combined with a third under the master berth and the buoyancy of the core, theoretically would float 12,000 lbs. The ends of the amas are concealed by curtains to reduce weight.

The insides of the boat are mostly painted fiberglass, or in the case of modules, gelcoated surfaces.

All plumbing is done with Whale’s rigid snap-together tubing system.

On deck and below, the various modules are caulked with 3M5200. On our test boat, the owner had unfortunately used bleach as a cleaner, which caused the caulk to yellow.

Accommodations

As noted earlier, there is a convertible dinette on the bridgedeck that would be fun to sleep in on humid nights; you can probably get a peek at the stars, too. This berth increases the sleeping capacity of the boat from five (belowdecks) to seven.

The starboard ama has a 56″ x 80″ double berth aft with 20-gallon water tank underneath. Amidships is a counter and general work space, and hanging locker outboard of the daggerboard trunk. Forward is the head with Lavac toilet, sink and shower sump.

In the port ama there is a single berth forward, the galley amidships with double stainless steel sink, Isotherm 12-volt refrigeration system, Seaward two-burner stove top, Bass electrical panel and Cole-Hersee battery selecter switch. Aft is a table and long seat. This is supposed to be the belowdecks gathering spot, but as Rob Malin pointed out, it’s rather awkward to have a conversation with someone sitting next to you. For face-to-face dialogue, you’ll have to go topsides. In any case, the table is hinged so that it can be converted to a berth, but we suspect most people will use it as Malin does, for navigation and a place to mount his laptop computer.

Headroom in the amas is 6′ 3″.

Hatches throughout are Lewmar Ocean series.

There’s a bit of long narrow stowage in the after section of the bridge deck, accessible through a lazarette behind the helm, and from either ama. The steering gear occupies part of this space and is reasonably convenient for maintenance. Similarly, there is another space forward of the bridge deck, again accessed from the amas.

On deck, there are two lockers forward, one for an anchor rode and another for fenders and cleaning supplies.

Between the bows is the tramp, which Malin says has held up well so far.

The dual companionways have arylic drop boards and hinged fiberglass covers; unfortunately, the builder has not yet figured out a way to lock them. Malin said owners are making their own locking mechanisms, sometimes with sliding rods.

Performance

We sailed with Dr. Malin on a cool November day off Cape Cod. To furl and cover or uncover the mainsail, you need to stand on the hardtop dodger, which is certainly strong enough. With a lamination schedule similar to the hull, it can easily support the weight of four or five persons and more. Lazy jacks keep the sail from flopping off the boom, but can catch the batten ends when hoisting.

There is a lot of power in the full-battened mainsail, which measures 366 sq. ft. But Malin said the boat doesn’t sail well under main alone. The jib, which furls on a Schaefer 2100 furler, is small at just 134 sq. ft., but makes a big difference, he said. We tried sailing both ways and agree. As soon as the jib was unfurled, we picked up considerable speed.

It’s a bit difficult to get good shape in the jib, which is self-tending on a block and traveler arrangement. A self-vanging CamberSpar would help, but wouldn’t allow furling.

The air was light, so after awhile we furled the jib and rolled out the optional screacher, a lightweight laminated sail that furls on a Schaefer 650 furler—too small for the job, we discovered, when the wind piped up and we had to bring it in. (Vermuelen says it’s the largest furler available for the Kevlar bolt rope in the sail. And, he added, we should not have headed up to furl the sail, but headed off and blanketed the screacher with the mainsail.) But in the meantime, the screacher made a huge difference, enabling us to do about 4-5 knots in 8 knots of breeze. This, of course, is the beauty of a multihull that hasn’t been hogged down with too much gear. Malin said he can carry the screacher up to about 45° to 50° apparent wind.

As the wind rose to about 15 knots, our speed exceeded 8 knots.

Unfortunately, Malin’s KVH wind instruments had just gone down so we were somewhat handicapped. Malin emphasized that one needs to steer this (or most multihulls) with instruments. Upwind, its sweet spot is about 38° to apparent wind, he said.

Monohull sailors may have difficulty understanding the need for instruments. The reason is that there is much less helm on a multihull, so it is difficult to steer a straight course by feeling the pressure on the tiller or wheel. Instead, you need to frequently check the compass, or the apparent wind angle indicator, which Malin has conveniently mounted overhead at the forward end of the hardtop.

Other than the main halyard, all sail controls are handled from the bridge deck, meaning that you don’t have to go on deck or even get wet if it’s raining. But they are located in different places, so if you’re single-handing, you will need to leave the helm for trimming the jib and furling headsails. The mainsheet traveler is right behind the helm, and the screacher sheets lead to blocks on the after ends of the amas, then to winches to either side of the traveler. During our test sail, Malin frequently flipped on the Navico hydraulic belowdeck pilot and purposefully moved from station to station to switch sails or trim them.

All the while, of course, the boat is level. There is, however, a much different motion than on a heavy monohull. It’s quick and at first it feels a bit jerky. When asked if he’d gotten used to it yet, Malin replied. “I don’t like it, but I’ve gotten used to it.” This is true of any comparatively short multihull; beyond about 40 feet, when the hulls can crest two waves at once, the motion settles down considerably.

Once into deeper water, we lowered the daggerboard, which makes a big difference in pointing ability and leeway. It’s a feature we highly favor. It was necessary, however, to come head to wind to get the board up, as any pressure on it makes the chore difficult.

Auxiliary power is provided by twin 9.9-hp. Yahama four-stroke outboard motors, each retractable and hidden under the bridgedeck seats. A 13-gal. fuel tank for each gives a cruising range of about 110 miles at 8 knots and double that at 6.5 knots with just one engine. Being four-strokes, and enclosed, the noise from them is modest. We did, however, notice some shuddering in the hulls from waves occasionally hitting the mounts.

Conclusion

There’s much to like about the Maine Cat 30: quality construction, good performance, open bridge deck design that can convert to a weathertight enclosure, and good looks. Nearly all the gear aboard is a cut above what you’ll find on many other production boats, such as the Bass electrical panel, Nexus instruments, Lewmar Superlock rope clutches, Cole-Hersee battery switch, Icom M45 VHF radio, 22-lb. Delta anchor, Siemens 55-watt solar panels, etc.

Like most new boats, the Maine Cat is something of a work in progress, with Vermeulen continually reworking and refining systems. To our mind, areas needing more thought include a better means of shaping the jib, a larger furler on the screacher, interior decor to tone down all the bare white fiberglass, and a means of locking the companionways.

The December 1999 price was $129,990, including sails, outboard motors, stereo, refrigeration and most of the gear mentioned in this review. It’s quite complete. Dinghy davits are optional.

We left our test sail thinking what a great boat the Maine Cat would be for coastal cruising, especially in the subtropics or tropics. For offshore, we believe a larger, longer multihull provides more comfortable motion and the increased righting moments that make passagemaking safe. Price, unfortunately, goes up exponentially with size. Vermeulen says the Maine Cat’s principal competition is the 33′ Seawind 1000, which starts at about $145,000 with sails, and the 33′ 6″ Gemini, which sails away for around $125,000.

Overall, we found the Maine Cat refreshing in its design, easy and fun to sail.

Contact- Maine Cat, PO Box 645, Waldoboro, ME 04572; 207/529-6500.