Remember the energy crunch of the mid-1970s? When Arab oil-producing countries moved to embargo oil shipments to the US, Japan and western countries and caused severe shortages? It was called the “energy crisis,” and it hurt industry. Families felt it as well when they couldn’t buy enough gas to fill their automobile tanks. To save fuel, the government tried to impose Daylight Saving Time year round.

The crisis effected the boating industry as well, more the builders of powerboats than sailboats. A few of them, including giant Bayliner of Everett, Washington, got the bright idea of starting up a line of sailboats. Soon they were under construction at three locations, in Valdosta, Georgia, Pipestone, Minnesota, and Arlington, Washington. Bayliner’s first boats in 1975 were, well, not the best looking or sailing boats ever built. These included the Buccaneer 210, 240, 270 and 320, all high-sided like layer cakes. In addition to increased windage from the high freeboard, the boats had shoal draft—24″ on the 210, 30″ on the 240. The combination resulted in boats that made a lot of leeway and didn’t point very well. At the big end of the line was the Bill Garden-designed Buccaneer 305 that, while a better-looking boat, also suffered from the same problems.

To improve the sailboat line, the Buccaneer Yachts division of Bayliner obtained some hulls designed by Doug Peterson. In this review, we look at the Buccaneer 305 by Garden (1976) and the Buccaneer 295 (1978) by Peterson. They are quite different in design but the same construction materials and methods were applied to each.

Later, Bayliner changed the name of its sailboat line from Buccaneer to US Yachts, and molds for some of the latter were bought by Pearson Yachts in the 1980s in a desperate attempt to save itself from bankruptcy. Pearson changed the name again to Triton, hoping to capitalize on the solid reputation of its groundbreaking Carl Alberg design of the same name, but this economy line of retreads failed to catch on and Pearson closed its doors in 1991.

Design

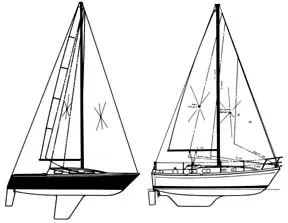

The 295, according to one source, was a three-year-old design when Buccaneer brought it into production in 1977. Intended to compete under the IOR rule, the bow is very fine and the stern pinched. The transom is a small triangle. This type of boat tends to go upwind better than off the wind, and a deep keel with high aspect ratio is certainly one of the reasons. The 295 draws 5′ 7″. We don’t have lines drawings for the canoe body, but the displacement/length ratio of 206 suggests a fairly shallow hull, and typical of IOR designs, there is a sharp tuck in the buttocks. The tall, double-spreader rig has a sail area/displacement ratio of 16.6. Together, these two numbers indicate a boat that should move fairly quickly.

The 305 is quite the opposite in the above respects. Both bow and stern are quite full, providing additional cockpit space aft and plenty of room for handling ground tackle forward. The toerail is wide and raised forward, making what you almost might call a bulwark; this adds security when changing sails or handing the anchor. Draft is shallow at 4′ 0″. The displacement/length ratio is 247 and the sail area/displacement ratio is 15.9. The keel has a large cutaway forefoot so that the leading edge of the keel is almost amidships. It has a flat run aft and then angles up into a small skeg. The spade rudder extends aft of the transom.

Construction

Long one of the world’s largest builders of boats, Bayliner has extensively researched and developed construction techniques to minimize man-hours yet produce a boat of reasonable quality. But we found several areas in which the Bayliner/Buccaneer method falls short of accepted practice.

Both the 295 and 305 are hand laid-up of alternate layers of woven roving and strand roving. In some areas, the laminate may be thin enough to cause oilcanning in large unsupported areas such as the forward topside sections adjacent to the V-berth. One surveyor’s report said of strand roving, “While strand is usually indicative of chopper gun construction techniques the length of the filament in this strand suggests that it couldn’t have been sprayed.” He called the standards to which the 305 was built as “fair,” and the 295 as “good.”

Why the difference? One significant area is in the hull/deck joint. On the 305, the hull/deck lap is fastened with self-tapping screws on 6″ centers. The seam is filled with silicone and covered by an aluminum mounting strip for the rubrail. On the 295, the deck laps the hull and is fastened with through-bolts on 4″ centers. It is glassed over on the inside and covered by an anodized toerail on the exterior. Through-bolts, which require two persons to install, are preferred over self-tapping screws, which can loosen over time, but can be installed by one person.

Bayliner stepped up quality on the 295 in another area, and that is in the use of backing blocks to distribute loads on lifeline stanchions, bow and stern pulpits. The 295 has backing plates here; the 305 doesn’t. Unfortunately, neither has backing plates on most other deck hardware. Without them, cracks in the fiberglass deck may result when, say, a heavy load is placed on a cleat, or someone on a dinghy or dock pulls on a stanchion to assist in boarding.

End-grain balsa and plywood were both used for deck coring in Buccaneer boats.

The original companionway drop (or “weather”) boards are thin. A good upgrade would be to widen the channels and build more substantial drop boards.

The overhead liners are foam-backed vinyl, which also may require replacement at some time. The 295’s interior hull sides have 1/8″ plywood stained to look like planking.

Secondary bonding of components to the hull, such as bulkheads, is generally good, as is the quality of gelcoat work.

Both the 295 and 305 have deck-stepped masts with 9-1/2″ aluminum compression posts that sit on either the keel (295) or on an athwartship wooden beam (305). On the 305, the double lower shrouds fasten to chainplates mounted on the sides of the trunk cabin, through-bolted to wood blocks inside. The upper shrouds fasten to external chainplates in the topsides of the hull, which are through-bolted to teak backing blocks. On the 295, the single upper shrouds, lower shrouds and intermediate stays share the same chainplates, through-bolted to reinforced bulkheads. There also is a babystay that attaches to a fore and aft track on the foredeck; unfortunately, the through-bolts have no backing plates. Running backstays were provided.

The original upholstery and trim had a definite 70’s look but these are upgrades that owners usually make every so many years anyway.

Accommodations

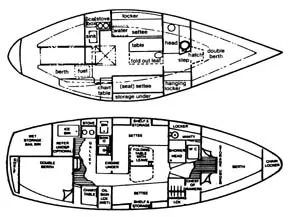

While both boats are roughly 30′, there is a substantial difference in space below, mostly due to the 305’s huge transom and wider bow. Both have a conventional V-berth forward, head with hanging locker, dinette and opposing settee in the saloon, and small portside galley. But in the starboard quarter the 305 has a large double berth whereas the 295 has just a quarter berth. Both have small nav tables; to work at them, one sits on the edge of a berth.

The size difference also shows up in headroom. The 305 has generous headroom in the saloon that’s alternately listed as 6′ 2″ or 6′ 5″, 6′ in the head. The 295 has just 5′ 11-1/2″ in the saloon, 5′ 6″ in the head. The 305 has a real dearth of handholds; not so the 295.

The 295 has a bridge deck at the same height as the cockpit seats. The 305 has only a 6″ lip to keep water in the cockpit out of the cabin. A bridge deck, of course, is much safer in rough conditions; in addition to doing a better job of keeping water out of the cabin than a drop board that may leak around the sides or float out of its channels, a bridge deck also reduces the volume of water that can collect in a cockpit (and as a bonus it opens up space below). One owner wrote, “She has a smaller cockpit than most 30s, and a tiny companionway and hatch, but I don’t understand not building in a bridge deck.”

Performance

Without question, the 295 is a superior performer. Its deep keel and lean hull form make upwind sailing a pleasure. Not so the 305, whose high sides and shallow keel make too much leeway.

The owner of a 1979 model 295 in New Jersey rated speed, seaworthiness, stability and balance as above average. Most call it a fun and exciting boat to sail. On the other hand, owners of the 305 rate speed as below average to average but are kinder in their descriptions of the boat’s seaworthiness and stability. One owner said, “In moderate air going dead to windward we lag behind, but in any wind conditions with the apparent wind 50° or above we walk all over Catalina and Islander 30s and Hunter 31s. She is heavy enough to carry much more sail than the newer hot rods.”

Indeed, the beam reach will be the 305’s best point of sail whereas the 295’s will be upwind—many IOR boats weren’t known for great handling under spinnaker.

The 295 was fitted standard with a 13-hp. Volvo two-cylinder MD7A diesel with tankage for 12 gallons of fuel. The 305 seems to have been delivered with several Volvo diesels from 25 to 35 hp. and between 42 and 50 gallons fuel capacity. Both have aluminum fuel tanks with vents and are grounded, but without shut-off valves. Owners of the 305 state she goes where she wants in reverse; a number have fitted three-blade propellers to help cure the problem.

Conclusion

The 295 and 305 are very different boats, with the former being best suited today as a club racer and the latter as a comfortable coastal cruiser. Construction of the 295 is superior in a number of ways but based on design and overall construction we do not consider either to be offshore boats.

These factors, on top of outdated design (295) and mediocre sailing performance (305) have taken their toll on the boats’ resale values. The Price History chart above shows how interest in these boats has nosedived over the years. Current BUC Research Used Boat Price Guide figures for the 295 are down near $10,000 and around $15,000 for the 305. In comparison, 1979 Pearson 30s and Tartan 30s are valued at about $20,000, and a 1979 Catalina 30 just a bit less at $18,950. Still, a well-maintained Buccaneer at a fair price may be an attractive deal…if you can live with its idiosynchracies in design and shortcomings in construction.

I’m having my Buccaneer 305 surveyed and checked for structural problems–cored hull, standing rigging, etc.

It’s served our family well for 40 years. Do you remember if the chainplates are bolted into the varnished teak boards inside the cabin? Or are the teak boards ornamental to cover the fasteners.

Also, the forestay chainplate does not extend down the stem of the hull as on most boats. Has that been a problem?

We just gunkhole around Puget Sound and I am conservative with canvas.

Any thoughts?

the teak boards are just a hollow cover.

Thanks. So is there wood backing under the teak?

Also, is the sea strainer like buried in the keel somehow?

just saw this, sorry… they have steel backing plates with 4 bolts. the lower one in the middle has a steel backing plate and that is on top of a wooden plate.

seacock for the engine is in the bilge area in the galley, is that what you meant? the keel by the mast has just a shallow bilge, any other seacocks are under the settees.

How are the 1982 US 35 that were derived from the Cooper 353?