With 85 hulls built to date, Freedom Yachts of Middletown, Rhode Island counts the Dave Pedrick-designed 35-footer as a solid success story. Freedom currently builds sailboats in three sizes, at 35, 40, and 45 feet, as well as the Legacy line of powerboats. The sailboat line stakes its identity on three points: sound naval architecture, high-quality construction, and sailing simplicity based on the freestanding rig and self-tacking jib. The line blossomed after the emergence of the sprightly and bulletproof Freedom 30 designed by Gary Mull in 1986. That boat, known to many readers, can serve as a useful benchmark in a discussion of the Freedom 35.

Design

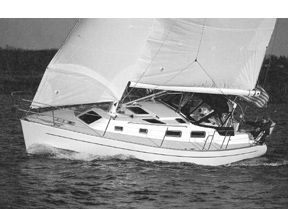

Pedrick’s designer’s comments speak of his intention to make the Freedom 35 a fast, easy-to-handle boat with ample cruising accommodations in the cockpit and belowdecks, as well as the ability to perform well at the club-racing level. To those ends he drafted a hull form that’s graceful and powerful, with a slightly aggressive look — a subtle sheer rising to a shallowly raked stem and a reverse-transom, with moderate overhangs at both ends and the beam carried well aft. The underwater hull is modestly round and full at the turn of the bilge and flattens as it runs aft — flat enough to allow the boat to surf in the right conditions. The transom carries a swim-platform scoop that blends well with the hull lines. A swim ladder is attached and can be lowered from the scoop. The helmsman’s seat can be removed to provide flow-through between swim platform and cockpit.

The cockpit itself is a bit small for a 35-footer — 7′ 3″ long by 5′ 9″ wide, with a T-shaped footwell aft to make space for the Edson wheel.There’s a large cockpit locker to starboard and twin lazarettes either side of the helmsman’s seat. The size of the cockpit makes it easier for a shorthanded crew to reach the sail controls, and the sides and coamings provide good support and security; stretching out under the stars, however, probably wouldn’t be worth attempting.

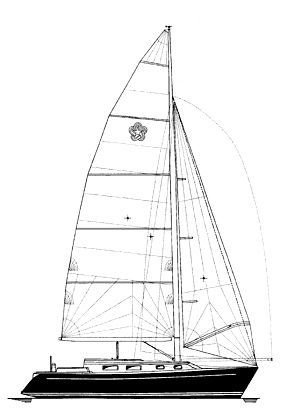

Like other Freedoms, the 35 carries a tall, unstayed carbon fiber mast with a big full-roach main and small standard jib, although the foretriangle on the 35 is relatively larger than that on the 30. The jib is fitted with a CamberSpar, a sort of internal wishbone that stretches the sail from the clew to a point on the lower luff. It articulates from tack to tack, more or less forcefully according to wind strength, thus helping shape the lower part of the jib upwind while allowing it to be winged out effectively downwind.

Unlike the Freedom 30, which was not rigged to carry more than its two basic sails, the Freedom 35 is offered with an optional overlapping headsail package, consisting mainly of a set of running backstays to oppose the headstay on the 3/4 fractional rig, and a set of primary winches in the cockpit for trimming. This set-up allows genoas and spinnakers to be hoisted to the hounds; the tip of the mast remains unsupported. In standard jib mode the runners aren’t needed — in fact, in the stock Freedom sailplan the jib exists more to create a slot upwind than to provide substantial horsepower itself; the headstay remains almost slack, tensioned only by the push of the CamberSpar, and luff tension is maintained by the jib halyard, as on a sailing dinghy.

Aside from initial cost, which is roughly $10,000 more than an equivalent aluminum spar and standing rigging would be on this 35-footer, the unstayed carbon rig has few apparent drawbacks — in fact, some of the cost of the carbon spar is recouped by the fact that the hull requires no chainplates, tierods or related supporting structures. It’s simpler and requires less maintenance than stayed aluminum rigs, and without the downward pull of the stays and shrouds, compression at the mast step is reduced.

Freestanding carbon spars are big and round at the partners and taper as they rise. They do obstruct airflow to the sail, especially down low, but as for windage it may be that without stays, shrouds, and spreaders they play about even with their aluminum counterparts.

In one of the few substantive changes to the F-35 since the introduction of the boat, Freedom a few years ago shifted the sparbuilding contract to Goetz Marine Technologies, known for its expertise in carbon fiber work. GMT produces a “lighter, stiffer” spar, according to Freedom spokeswoman Roe O’Brien, who also says that there have been no reported rig failures on the 35, before or after the change. The spar comes with a transferable 10-year warranty, or a lifetime warranty to the original owner.

It may be that the only shortcoming of the carbon spar these days is psychological: The scarcity of wires can be disconcerting. We all tend to grasp at the shrouds when we’re working at the mast or coming aboard amidships, and when they’re not there, something seems askew with the world.

The boat is offered with two keel options, a deep fin with a Pedrick-designed “whale tail” profile, or a shallower (not to say shoal-draft) wing keel. The whale-tail rudder is a big, high-aspect foil on a carbon fiber stock. Owners report that Freedom’s and Pedrick’s extra efforts in designing responsive steering have paid off: The boat turns quickly and accurately, and provides good feel through the Edson system.

There’s little question that the deep keel provides better lift than the winged version. This translates into acceleration in a puff, less heeling and slippage as boatspeed increases, and often less leeway once the boat is up to speed.

For some owners, the Freedom 35’s draft may be the hardest nut to crack. The deep keel is quite deep at 6′ 6″, and the wing keel, at 4′ 6″, isn’t all that shallow.

Construction

Hull construction standards are at the top end of the production scale — skins of biaxial and unidirectional E-glass with vinylester resin, sandwiching an end-grain balsa core. The hull/deck joint is bonded with 3M-5200 and through-bolted on 6″ centers. There’s a transferable 10-year warranty against hull blistering.

Down below, furniture is fastened to the bulkheads, and the bulkheads are glassed directly to the hull. There are solid fiberglass transverse supports under the floorboards. There are five Lewmar hatches on deck, 19-3/4″ square in the forward and main cabins and 10″ square over the head, galley and aft cabin. All ports are 316-grade stainless steel — another indication that these boats are stretching outside the standard production mentality. Stainless ports add significantly to the builder’s initial cost, and certainly bump up a new boat’s price, but without question they save the owners problems and headaches, and of course this ends up saving Freedom time and frustration.

The Yanmar 3GM auxiliary lives under the L-section of the port settee. The shaft exits the transmission and emerges underwater about a foot to port of the keel and at a 5° angle to the centerline.

This engine and shaft placement serves several purposes: First, it creates more room throughout the area of the aft cabin, companionway, and head. Second, it puts the engine’s weight in a better fore-and-aft position without sacrificing much balance athwartships. Third, it makes for very good engine access everywhere but on the engine’s port side, and even that’s not bad. Fourth, it helps concentrate plumbing through-hulls in one zone, under the galley sink. Fifth (and this is the feature touted by Freedom) it’s a built-in correction for “prop walk” when the engine is in reverse — the slight angle of the shaft off centerline helps neutralize the tendency of the left-rotating prop to drag the stern to port.

On deck, sailhandling hardware includes two Harken two-speed winches at the aft end of the cabin trunk, and a Harken traveler. Halyards, reefing lines, main and jib sheets, and traveler controls are led through Lewmar stoppers.

Accommodations

Belowdecks the Freedom 35 is laid out to provide good comfort and privacy for two couples, with full cabins fore and aft. Each has standing headroom (6′ 1″) behind closed doors, each is ventilated by two opening ports and a hatch, and all bunks are 6′ 7″ long. There’s room for two more people on the settees in the saloon, and an equipment option that allows the port settee to be converted to a double berth. Underway in standard layout the leeward settee is comfortable, but for sleeping at anchor it makes sense to remove the side cushions for more elbow room.

The saloon has a warm, traditional feel, with varnished cherry cabinets, hull ceilings, and handrails. The cabin sole is teak and holly, while the overhead is covered with a removable vinyl headliner. Headroom throughout the saloon is 6′ 2″.

The cabin table folds up and stows against the bulkhead to port. This opens up lots of valuable space for people to wrestle with bathing suits, foul-weather gear, sleeping bags, duffle bags, grocery bags, and the various other bags that make their way aboard. Stowage for personal gear is good in the fore and aft cabins and adequate in the saloon, where the absence of chainplates or tie-rodes is a help.

The head compartment is to starboard of the companionway steps. This is always a smart arrangement on a single-head boat: It keeps saloon traffic to a minimum and makes use of a wide part of the hull for more space; in this case the compartment includes a separate shower stall with teak grate and a proper wet locker. Stowage for toiletries in the head is adequate; more importantly, with the shower stall isolated there’s less chance for everyone’s stuff to get soaked when someone takes a sloppy shower.

The L-shaped galley, according to Freedom Yachts, incorporates many features suggested by Freedom owners. There are two deep stainless steel sinks on the counter section athwartships, and a gimballed Force 10 stove/oven to port. The ice chest incorporates a nice touch — a separate section and door for drinks and quick snacks, which allows the main part of the chest (8.5 cubic feet) to stay closed most of the time.

Two PS survey respondents bemoaned the lack of counter space in the galley. This space was surely sacrificed to the enclosed standing room and hanging locker in the aft cabin. On a boat this size, some things have to give, and in this case the working areas below — galley and nav station — gave it up to the head and the private cabins.

There are no standard foot pumps for fresh or salt water in either the galley or the head. With today’s reliance on pressure water systems this omission is commonplace among boatbuilders. Admittedly, it adds expense and labor on the builder’s side, and there may not even be that much demand from buyers — but it’s poor practice, in our view, especially noticeable when batteries or water supplies are low.

Performance

Soon after it was introduced we were able to sail the company boat, Hull # 1, in conditions that ranged from about 18 knots to nothing. That boat, rigged with a 120% Mylar genoa, was clearly a fast and nimble performer, particularly in light air and downwind. It’s chief failings were the lack of a dedicated mainsheet winch, and a traveler system that was too small for the loads imposed by the big sail in heavy air. Both of those problems were addressed early in the production run of the boat.

Part of the Freedom 35’s agility comes from the big, light whale-tail rudder; other contributing factors are the balance of the sailplan, the self-tacking jib, and the extra roach on the mainsail, which acts as an airbrake in jibes. With this combination the boat can be spun around upwind or down in a small radius with sails trimmed and locked. It may not be pretty, but it can be done.

As the wind increases, the unsupported tip of the carbon fiber spar will tend to sag to leeward, automatically depowering the sail, but also creating more and more weather helm. The F-35 mainsail needs to be reefed sooner than later — there’s plenty of power left in the roachy main, the boat stands up straighter, the rudder is relieved, and everything speeds up. The boat is “simple to reef with minimal or zero loss of speed,” says one owner. “Very little weather helm in gale warning winds.”

The sail area/displacement ratio of 19.8 on the standard rig is respectable, but there’s an inevitable lack of headsail power upwind in many conditions, no matter how big the main and how closely sheeted the jib. No doubt this is one reason Pedrick increased the size of the foretriangle — not only to increase racing options, but to make life happier for cruising sailors willing to do some cranking in order to punch their way upwind. (Of course, at that point the Freedom’s sailplan loses a substantial measure of its freedom.)

Most F-35s today are sold with the overlapping jib package, says Freedom’s Roe O’Brien, but few are raced actively. (The standard boat carries an average PHRF rating of 114.)

Conclusions

Whether or not people race these boats, Dave Pedrick and Freedom certainly have succeeded in their design aims: The Freedom 35 is a comfortable performance cruiser, well built, easily handled, seaworthy, and attractive looking.

With a real voice in design issues from the outset, and the ability to work with the company on semi-customization of new boats, veteran owners are a loyal bunch. “In general, people who buy Freedoms become big devotees,” says O’Brien.

While a new Freedom 35 costs $188,200, second-hand boats cannot be had for a song. The BUC Used Boat Price Guide lists the high and low of the average price for a 1993 model Freedom 35 as $107,000 to $118,000. For a used 1999 model there’s quite a jump: $183,000 to $201,000. These figures reflect actual sale prices of boats, reported by brokers back to the BUC network. A look around for current asking prices showed exactly one boat available, in Stamford, Connecticut, for $149,000. (Not for long, we think.)

Contact- Freedom Yachts, Inc., 305 Oliphant Lane, Middletown, RI 02842 800-999-2909.

Also With This Article

Click here to view Owner Comments.