The Columbia 9.6 is one of the last boats built by this pioneer of fiberglass sailboats. The 9.6 stands for meters and distinguishes it from Columbias earlier boats, which used feet: Columbia 22, 26, 28, etc.

According to Heart of Glass, former PS editor Dan Spurrs encompassing history of the fiberglass boatbuilding industry, Columbia was founded by 25-year-old Richard Valdes and Maurice Thrienen in 1960. Valdes had graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles in 1956. Thrienen, 10 years older, had served in the US Navy submarine service during World War II. In 1957, Thrienen was selling fiberglass supplies.

The company was first named Glas Laminates, later Glass Marine Industries. Within a few years, the name was changed to Columbia, after the successful introduction in 1962 of the Columbia 29, designed by Sparkman & Stephens. It became, along with Jensen Marine that built the Cal line, one of the largest builders of fiberglass sailboats. Later they built a line of power cruisers called the Express 30, 36 and 42. In its heyday, Columbia exported boats to Europe.

Learning early on not to put all their eggs in one basket, the young men also built fiberglass camper tops, shower stalls and chemical toilets. Perhaps this was because Vince Lazarra had bought controlling interest in their company. Lazarra had come out of Chicago, where he owned a foundry, to join with Fred Coleman in Sausalito building the first production fiberglass sailboat, the Bounty II. When they sold out to Grumman, Lazzara moved south to Costa Mesa to join Valdes and Thrienen.

In 1964, Columbia opened an East Coast facility in Portsmouth, Virginia.

By 1965, Columbia built the largest production fiberglass sailboat-the Columbia 50, the boat in which authors Steve and Linda Dashew made their first circumnavigation. The 50 was successful both on the race course and in numbers sold.

Bill Tripp designed the 50 and a slew of similar, flush-deck racer/cruisers-among them the 26, 34, and 43. Bill Crealock was commissioned for the hugely popular Columbia 22 and Charley Morgan for the Columbia 40, based on his Sabre, which nearly won the 1964 SORC. The Columbia 31 was based on Morgans Paper Tiger, which did win the SORC-twice.

In 1967 the trio sold out to the Whittaker Corp. and Lazzara moved on, building houseboats for a time before his no-compete clause expired, when he started Gulfstar in Florida.

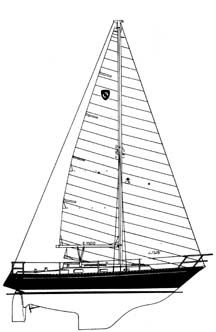

The “meter” line of sailboats was introduced in the mid and late 1970s. All were designed by Australian Alan Payne, whose 12 Meters Gretel and Gretel II had competed tenaciously for the Americas Cup.

When Whittaker decided to unload Columbia, it was the molds for the Columbia 7.6, 8.7 and 10.7 that were sent to Aura in Huron Park, Ontario, Canada. Aura built some of these models, but only between 1984 and 1986.

The Design

Columbia called Paynes “meter” boats “Widebody Supercruisers.” While some other models in the line may have had wider beam than most of their contemporaries, this isn’t the case with the 9.6’s 10’2″ beam. For example, the 1973 Ranger 32’s beam is 10’10”; the Paceship 32 10’6″ and the C&C-designed Ontario 32 11’0″. Yes, there were boats with narrower beams, but these were generally older designs.

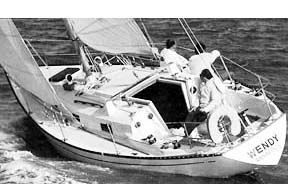

The company also hyped the 9.6, introduced in 1976, as having a …racing physique. And a cruising heart. The production run was about three years. Like nearly all major production builders, Columbia was after the elusive ideal of the racer-cruiser, trying to convince buyers that you really can have it all: Win races and cruise in sheik-like comfort.

When first introduced, Columbia said it was organizing one-design fleets around the country- la the Tartan Ten-but we don’t recall this happening, at least on any large scale.

The overhangs are fairly generous, especially the almost clipperesque bow (because of its slight concave shape), which gives the boat just a 23’9″ waterline length. Draft is 5’6″, which is a bit deeper than many 32-footers, and a nice concession toward the fast end of the performance continuum.

The most interesting and distinguishing characteristic of the 9.6, however, is the skeg between the keel and rudder. Of it, designer Payne said, “The skeg of the 9.6 was carefully designed to eliminate the separation wave which is commonly seen on the weather side towards the stern of a medium displacement yacht when it is heeled over and going fairly fast.”

When viewing the plans, it certainly seems that this long skeg makes for too much wetted surface area.

Payne also noted that medium displacement was chosen in order to provide reasonable space inside plus the structural strength necessary for a lasting investment.

Unlike the 8.7 Meter, with its unusual wine glass transom, the 9.6 has an IOR type transom-a small triangular shape.

In any case, shes better looking in the flesh (if one can say that about fiberglass) than on paper.

The displacement/length (D/L) ratio is a hefty 350 while the sail area/displacement (SA/D) ratio is a modest 15.3. Given these numbers, it’s hard to see how this boat can win many races, despite the fact that its waterline length increases as it heels.

Construction

The older and more successful Columbia models, such as the 26 and 36, all had molded fiberglass pans glassed into the empty hull; these pans incorporated the engine beds, berths and most of the other “furniture.” Such “unitized” interiors, as Columbia called them, greatly speed up construction as it reduces man-hours-a key factor in the cost of building a boat. They do, however, have their drawbacks, as we have pointed out many times. Compared to plywood interiors tabbed to the hull, fiberglass pans are poor acoustic and thermal insulators (they are noisier and condense more moisture), can make access to parts of the hull difficult, severely limit customization, and are difficult to rebond to the hull should they ever come loose.

That said, the Alan Payne “meter” line has built-up wood interiors, which we much prefer.

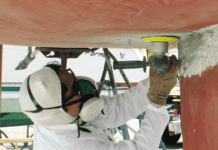

To stiffen the hull, longitudinal stringers are glassed in both below the cabin sole and above the waterline. Columbia literature doesn’t specify what the stringers are formed over, but theyre probably wood or foam. The hull laminate itself is solid glass. The deck is cored with balsa.

Ballast is external lead with 3/4″ keel bolts.

The rudder is a hollow fiberglass shell filled with foam; the rudderstock is stainless steel. Owners of the 8.3 noted a number of rudder failures but we did not hear this complaint about the 9.6.

A molded drip pan is fitted below the engine to prevent oil from migrating into the bilge.

An important feature for offshore sailing is the tabbing of structural bulkheads to the deck. This isn’t possible when molded fiberglass headliners are used. The 9.6 has a fabric headliner with zippered panels so the bulkheads can be bonded to the deck and so one can access the nuts that hold deck hardware in place.

The standard cabin sole is wood but of what species we are uncertain. A teak and holly sole was optional.

The 9.6 has a lot of teak veneer plywood and solid teak trim in the interior. Otherwise unfinished areas of the hull were coated with gelcoat, which makes them easier to clean.

All through-hulls are fitted with proper, positive-action, bronze seacocks, not gate valves that can freeze and whose handles may then twist off in your hand.

The toerail is an anodized aluminum extrusion similar to that popularized by C&C and that allows one to shackle a block anywhere; it also strengthens the hull-deck joint.

The electrical system has circuit breakers, but not many circuits. A good upgrade on many older boats is to install a new panel with more circuits. Be sure 12VDC and any 110VAC shore power systems are on separate panels per American Boat & Yacht Council (ABYC) standards. Some older boats may have combined panels. Underwater metal parts such as through-hulls are electrically bonded together and to a sacrificial zinc anode, which means that there are wires connecting them so that they all have the same voltage potential. This should minimize loss of metal to galvanic corrosion. The boat also has a lightning ground system, which directs current through the mast and shrouds to ground (water).

Standard steering was a tiller; in 1977 wheel steering was a $950 option. The rig is a keel-stepped masthead sloop with double lower shrouds.

Most owners responding to our Boat Owners Questionnaire rate construction quality as excellent, despite the fact that nearly all respondents complained about problems with the hull-sump joint. A few also noted gelcoat crazing.

Several owners said that the engine exhaust installation was incorrect and allowed water to backflow into the engine. This can be an expensive repair so check any boat you’re considering purchasing to make sure this has been taken care of. Often the cause of water backflowing into the engine is the wrong placement of the waterlift muffler, or a muffler not large enough to hold the volume of water between it and the exhaust fitting in the hull.

Accommodations

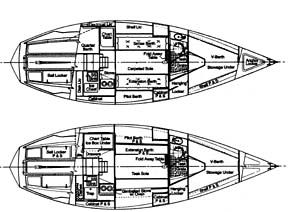

The interior plan is straightforward and functional. Two layouts were offered during the production run. Hulls #1-90 have twin pilot berths in the saloon. Hulls after #90 have an extension berth and pilot berth to starboard and a settee/berth to port. This later plan also has a quarterberth to port, whereas the earlier plan has no quarterberth, but instead an ice box with chart table over. In both layouts there is a V-berth forward plus enclosed head and hanging locker. Maximum headroom is 6′ 1″.

An early brochure made this point:

“Teak Cabins Vs. Teak Trim. Theres a Difference. Youll find a lot of boats that claim ‘teak interiors.’ But look closely. Unlike many ‘price boats’ that offer a teak bulkhead or two and some teak trim, the 9.6 cabin is all teak. Teak doors, cabinets, drawers, bulkheads, lockers, shower grate. Teak wherever you look. You can even get a teak sole. Only the counter and table tops, that have non-mar surfaces for frequent cleaning, are not teak. But even they have teak sea rails.”

You get the idea.

The 1970s was a time when everyone wanted gobs of teak-down below and on deck. Teak decks were considered the classiest. Teak is a low-maintenance wood and highly rot resistant, owing to the high amount of oils in it. Ignored, it turns a weathered gray, which is fine if you don’t mind a dingy appearance. If, however, you want to enjoy the beauty of oiled or varnished teak, teak suddenly becomes much more maintenance-intensive, requiring sanding, taping off, and the application of an oil or varnish by brush. While many owners happily or grudgingly perform these rites of spring (and summer and fall if theyre smart), during the 1980s more boat owners began deciding theyd be willing to forego the beauty of natural teak for more time sailing. Builders were quick to pick up on this trend and began stripping teak off the boats above and below. Today it’s not uncommon to see a big boat with no teak on deck and more judicious use of it below.

Performance

Designed to the IOR (International Offshore Rule), the 9.6 had a 21.7 rating. One of the more interesting comments from owners is the complaint that the boat is difficult to make perform to that rating. Typical of these remarks was this summation from the owner of a 1977 model in Massachusetts: Sails well, good in chop, handles well, however she will not race to her rating, either IOR or PHRF.

The average PHRF rating is around 189 seconds per mile, though there are few fleets around the country.

As with most boats, owners’ ratings of upwind and downwind speed, compared to other boats of similar size, are no doubt exaggerated. Most rate upwind speed as excellent and downwind as above average. A few perhaps more realistic owners give ratings of average and below average. In any case, nearly all agree that the boat doesn’t perform as well off the wind, which is generally the case with IOR-type hull forms.

In the same vein, owners rate stability and seaworthiness as very good but nearly all downgrade the boat for balance-again, particularly off the wind. “Must work controls to maintain balance,” said the owner of a 1977 model in Pennsylvania.

When you study the sailplan you see a very high-aspect ratio mainsail and large overlapping genoa. In recent years, the trend has been in the opposite direction, back to smaller headsails (even self-tacking jibs of 100% or less) and larger mainsails, if for no other reason than most people don’t like to grind winches.

Several small diesels were supplied with the 9.6, including the 10-hp. Volvo MD6B and the MD7. Most owners complain that these powerplants are too small to move the boat at desired speeds, especially into head seas. Many have repowered with larger engines. If we were looking for a used 9.6, wed hope for one with a newer and larger diesel. We noted that some repowered with early model Q series Yanmars, which prospective buyers should know are not the same as the current generation, and are quite a bit noisier.

Conclusion

The Columbia 9.6 is one of the better looking “meter” boats from designer Alan Payne. The basic structure is quite strong and suitable for offshore sailing.The interior may, to some eyes at least, be a bit on the dark side owing to all the teak. Of course one could paint over some of it, but that seems sacrilegious… even if the amount of teak is on the excessive side.

We could make do with either of the two interiors. Pilot berths make good sea berths and also are good places to store frequently accessed gear. Fit the berths with adjustable weather cloths to keep stuff from flying across the cabin. One owner said that the interior was great for overnight races, and we assume he’s referring to the four berths amidships (or three in the saloon and one quarterberth in the early model). Kids like pilot berths, too.

The boat is not a screamer, but acquits itself quite nicely upwind. A spinnaker helps performance off the wind, though the helm will need attention.

Asking prices range from the high teens to low twenties, averaging around $21,000.

Also With This Article

Click here to view the Owner Comments.

Click here to view the Used Boat Price History.