Now back on the production line at Pacific Seacraft after a three-year hiatus, the Dana 24 is a pricey, seaworthy, two-person cruiser. She will satisfy the criteria of a couple interested in owning a moderate-displacement boat designed to sail in tough conditions. Though comfortable, her layout is seagoing—she’s not a dockside entertainment center.

The Dana has had a bumpy production history. After a successful run from 1984 to 1998, she was relegated to the bench when Pacific Seacraft began producing several bigger boats —a 40-foot companion to the PS 34 and 37, a 38-foot trawler, and the Nordhavn 40 trawler. Production facilities were simply overstretched, and the Dana had to sit out for a few years. She was reintroduced in 2001, and is enjoying a successful renaissance.

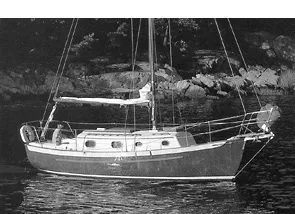

We sailed Chris Humann’s sloop-rigged Carroll E, hull #39, built in 1986, on San Francisco Bay. By day’s end we were convinced of the boat’s suitability as a daysailer when the wind pipes up, or as a cruiser that can be easily singlehanded.

The Company

Pacific Seacraft was founded by Henry Morschladt and Mike Howarth in 1976. They first produced 25-foot daysailers. Like many boatbuilders, the company suffered the hardships of the marketplace in the 1980s, when ownership was transferred to Singmarine Industries, Ltd., of Hong Kong. It has been owned by an individual investor since 1998. The company’s niche is high-end, well-constructed bluewater cruisers.

The company has operated for several years under the direction of Don Kohlmann, a veteran America’s Cup racer and former owner of Ericson Yachts. Kohlmann reports that Pacific Seacraft has produced 1,950 boats so far, and that the current annual production level is 40 to 50 boats.

Design

Designer W.I.B. “Bill” Crealock says his boats are “designed to deliver crews to their destinations in comfort, good shape, and refreshed.” His cruisers have been crossing vast expanses of blue water and gracing the pages of sailing magazines since he opened a design studio in California in 1958. Prior to setting up shop, he received a degree in naval architecture from Glasgow University in Scotland. Following graduation, he spent eight years learning about boats while cruising the Atlantic and Pacific aboard sailing yachts from 40 feet up, including a stint as sailing master on a 105-foot schooner undertaking a scientific expedition for the US Navy.

Crealock’s designs range in size from dinghies to a 100-foot catamaran. Among his production designs are the Excalibur, Islander, Columbia, Westsail, and Cabo Rico. “I estimate that about 8,000 boats have been built to these designs,” he says.

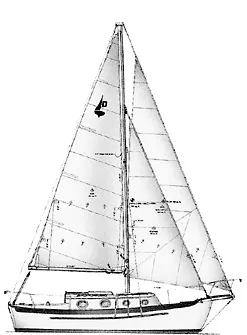

The Dana 24 shares many of the same design characteristics as her larger sisters: clean lines, traditional ocean-cruiser appearance, nearly plumb bow and stern, comfortable spaces belowdecks. Her cabintop (with bronze ports) is a bit high, but the elevation produces more than 6 feet of standing headroom. Coupled with a 36-inch bowsprit, she presents a jaunty profile.

Crealock describes the basic aim of the design: It’s “the smallest boat in which a couple could cruise offshore in safety and reasonable comfort, with an enclosed head… The hull would have to be roomy to carry a fair amount of weight in tankage and supplies. She would not be a light-displacement boat. Displacement was not considered a disadvantage since no other single factor eases motion, in my opinion.”

He describes the sailplan as “balanced, designed to produce good upwind performance.” The boat can be configured as either a masthead sloop or a cutter.

The underbody features a long, moderately deep keel with a fully supported rudder and cut-away forefoot, a shape that reduces unnecessary wetted surface and gives better maneuverability in close quarters, as we experienced during our test sail.

Construction

Construction techniques for the Dana mirror those employed in the construction of other Pacific Seacraft boats. Though she’s the runt of the litter, all of her deck hardware is of the same quality as her big sisters.

The layup schedule calls for a coat of ISO-NPG gelcoat mat laminated in vinylester resin. The skin coat is 3- oz mat followed by three layers of 2415 bi-axial roving. Additional layers of 2415 are applied at the keel, rudder post, and chainplates. The hull is 5/8″ thick at the bottom.

The hull is solid fiberglass, but the transom is cored with plywood to produce stiffness for the stern ladder and steering vanes.

The interior is constructed of plywood-reinforced fiberglass faces that form the furniture and a bulkhead matrix, all of which are bonded with bi-axial roving. The process produces a strong grid that also allows access to the hull behind cabinetry.

The hull-deck joint consists of opposing flanges on the hull and deck molds, joined to form a bulwark. The joint is bedded in 3M 5200 and through bolted, after which an aluminum toerail is bedded in 3M 5200 and bolted through the joint.

Deck coring is 0.5″ Baltek AL-600 balsa encapsulated in layers of 3-oz mat and 24-oz woven roving. Additional plywood reinforcement is laminated in all areas where deck hardware will be installed.

Ballast is 3,200 pounds of pre-cast lead bonded into the interior of the keel fin.

She is well built. In Kohlmann’s words, “This boat might also serve as a bomb shelter.”

Deck Layout

The first impression upon stepping aboard is that you’re on a miniaturized version of a traditional, cutter-rigged cruiser. The bowsprit and pulpit, which add three feet to her LOA, create visual space forward, and the long cockpit seats provide “full-size” seating.

The aluminum mast, made by LeFiell, is deck-stepped, and protected with a layer of linear polyurethane. It’s supported by a compression post belowdecks.

Deck-stepped masts are frowned upon in most offshore circles, but Dana owners are more likely to be sailing protected waters, and even bridge-covered waterways, than oceans, and a full section of mast belowdecks in this boat would be a serious intrusion into the cabin.

A single set of unswept spreaders bolster standing rigging of 1×19 stainless steel wire connected to bronze turnbuckles. Halyards are external, leading to mast-mounted Lewmar 8 winches. This is a simple, traditional set-up, but the deck mold has flat surfaces on which turning blocks could be installed, allowing relocation of winches aft. It’s hard to say whether such relocation would be worth it on a boat this size, but it’s good to have the option.

The only backstay adjuster is a turnbuckle on the transom, so sail shape will be controlled by halyard, mainsheet, vang, and outhaul. Ball-bearing blocks for the mainsheet controls are located on a short traveler on the transom and at the end of the boom. The mainsheet fall is angled aft, so it gives up some power in order to be out of the cockpit.

Jib sheets are led to the 5″ tall bulwarks: It’s clear that she won’t point as high as a Farr 40. There’s a second sail track mounted inboard atop the coachroof for a working jib or staysail.

Stainless steel chainplates for upper shrouds and fore-and-aft lowers are fastened in the hull with stainless carriage bolts and backing plates. This method produces a strong structure, and eases movement along the decks. With the boat heeled 15 degrees during our test sail, we found that the two teak handrails and six shroud bases provided handholds at every step.

The cockpit can accommodate up to six adults for sailing or lounging. The seats are 6′ 3″ long, 18″ wide, and outboard can’ted backrests are 13″ tall. The tiller can tilt up out of the way when not in use.

Crealock designed long seats at the expense of space belowdecks because, “those seats need to be long enough to allow crew to sleep comfortably outside.” This is exactly right, as anyone will agree who has had to spend a stifling night below while a traveler track rested comfortably across the cockpit, or an oversized wheel area took up all the room where sleepers’ feet should be.

The cockpit footwell is 51″ long, 20″ wide, and 14″ deep: Guests have plenty of foot space, but also convenient bracing when the boat is heeled.

Though the cockpit seems proportionately large for a small vessel, Crealock also says that the combination of her buoyancy, high coamings, and 1.5″ scuppers will prevent her being swamped in a following sea.

The starboard cockpit locker houses two batteries, and provides access to engine hoses and the holding tank. A 25 GPM Whale Gusher manual bilge pump also is close at hand.

The port locker is 54 inches long, 36 inches deep and 30 inches wide. The owner of our test boat found adequate storage there for a small sail, dock lines, fenders, and a spare anchor. The space also houses a pressure pump for the kerosene stove on older boats. Newer boats have propane stoves, with a locker for tanks in the corner of the cockpit to port.

Access below, and ventilation, are provided by a companionway 28″ high and 26″ wide, enclosed by a 35″ long fiberglass hatch.

The cockpit has a watertight, removable sole, a Crealock signature. Unscrewing four bolts allows removal of the sole and access to the sides and aft end of the engine. The fuel fill is on the companionway step—simple plumbing to the fuel tank, but a bad place for a fuel a spill.

The bow is equipped with two cleats and a hawsepipe. The owner of our test boat told us that a 25-lb CQR anchor had held her in 40 knots of wind in Tomales Bay on the California coast. The hawsepipe should be sealed when sailing offshore.

All of the deck hardware is installed with backing plates and caulked on both sides with polyurethane. The owner of our test boat pointed out that the flat brace for one stanchion is bedded atop the nonskid, which could allow water into the deck coring if fasteners are not properly sealed.

Less than ideal was a 6″ loop of wire connector on deck at the base of the mast. It’s for attaching wires for mast lights and VHF, but it looks to us like something that could easily be kicked loose, or loose enough to invite electrical shorts and leaks. We observed the same arrangement on three used boats. According to Don Kohlmann, it’s left that way for the convenience of owners who frequently trailer their boats, or who live inside bridges and have to lower their masts often.

Accommodations

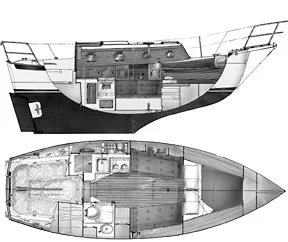

Pacific Seacraft boasts that the area belowdecks is “fully 50 percent larger than any other boat of similar length.” In the absence of proof to the contrary, we believe them: This 24-footer has 6′ of headroom in the saloon and 8’6″ of space between the foot of the companionway and the V-berth. The V-berth is large enough for two 6’2″ adults to sleep comfortably. Settees port and starboard measuring 4’6″ long convert to 6’6″ berths. The galley is large, there’s an enclosed head to starboard, and there are even a few cubic feet of stowage space.

The feeling of spaciousness is enhanced by the combination of hand- rubbed oiled teak surfaces accented by a removable white headliner, eight shiny bronze ports, a big Bomar hatch to introduce light, and the lack of a bulkhead forward. Kohlmann notes that newer boats have rectangular ports that are more durable and have better seals than their oval-shaped predecessors.

In the bow, the anchor locker drains into a PVC pipe leading to the bilge. This helps keep odors out the saloon, but requires good bilge cleaning and maintenance.

Wide shelves outboard of the V-berth offer storage for books and miscellaneous items. The area below the berth is occupied by a 30-gallon stainless steel water tank fitted with an inspection plate. A second, wide-open storage space below the berth is 20″ long and 28″ deep. Additional storage for clothing is in two drawers located under the center of the berth.

Crealock has cleverly hidden the dining table under the berth. When needed, it slides aft around the compression post, and offers seating for two at a 30″x20″ table.

Storage amidships is in open bins behind and above the settee backrests. Optional cabinetry provides four cabinets above the settee, and two bookshelves.

The navigator’s station consists of a small hinged desk at the forward edge of the galley that folds out of the way when the settee is in use. It’s one of the compromises involved in the design of such a small boat. It’s tiny—only 18″ wide and 13″ deep.

A removable counter atop the two- burner gimbaled stove measures 20″x 25″. There’s a bit of additional counter space atop the ice box, aft of the 10″ x 14″ stainless sink. Storage outboard is in two enclosed cabinets, and a plate and glass holder.

The ice box on new boats measures 3.5 cubic feet. The owner of our test boat carries two five-pound blocks of ice that he says last five days in 70- degree weather. No surprise: the reefer has 3″-7″ thick insulation.

Electric panels are tucked in the aft end of the galley, and on the port bulkhead.

A hanging locker aft of the starboard settee measures 14″ wide by 34″ deep, and is large enough for two sets of foulies. It’s enclosed by a vented door that aids air circulation.

With clearance measuring 32″x21″, the head can only be described as cramped. The vanity is 12″ wide, and fitted with an oval sink.

A storage compartment aft is 17″ wide and 30″ athwartships; it allows access to a sea water filter and sea cocks.

Power

Engines on older boats were Yanmar diesels developing 16 horsepower; that engine moved our test boat at hull speed into a chop at three-quarters throttle. Newer boats are equipped with 2-cylinder, 18-hp Yanmars.

Companionway steps can be removed for access to oil and fuel filters. The fuel tank is located on the centerline under the cabin sole. Fuel capacity is 18 gallons.

Performance

We sailed the sloop-rigged test boat under full main and 110% jib on a chilly San Francisco day in blustery conditions, and were impressed with the performance and seakindly motion of the boat. A Kestrel windspeed instrument registered 12-15 knots of wind.

The GPS registered boatspeed at 5.7 to 5.9 knots over the ground as we sailed close-hauled with sheets barely started. As we hardened up farther, moving the traveler up and trimming the jib board-flat, we heeled to 20 degrees. Speed held at 5.2 to 5.4 knots, but she was not comfortable and we were sliding to leeward.

We eased sheets and saw speed reach 6.8 knots over the ground while sailing into a flooding current on a broad reach in 13.5 knots of breeze. The boat felt lively, and responded quickly to each movement of the tiller.

The owner typically reefs the main only when wind speed reaches 18-20 knots; otherwise the boat develops excess weather helm.

Later, in light air, we sailed at 3.5 to 4 knots on a beam reach, and felt sluggish with the 110% headsail. In lighter windspeeds the boat feels her weight. A bigger genoa, or an asymmetrical cruising spinnaker tacked to the sprit would be a big help.

Conclusions

The Dana 24 is a cruiser that will feel at home anywhere winds blow more than five knots. She’s a proven performer in short, choppy conditions, and sailing down a Pacific wave. She’s well built, and outfitted with top quality gear.

During her first stint in the marketplace, prices for new boats ranged from $70,000 – $100,000. At that time, owners were offered wide latitude in the design of spaces belowdecks, gear specifications, and deck and hull colors (all of which increased the price). Though construction of a boat still requires 9-10 weeks, Don Kohlmann says she’s now built more like a production boat with fewer changes to the basic configuration.

Today a new boat has a base price of $70,000, including Ullman mainsail and jib. Options like Harken roller furling, a boom vang, shore power, and instruments will run the tab up to $80,000 quickly.

No question—that’s a staggering amount of money for a 24-foot monohull. But there’s obviously a niche well-defined enough to justify production, and that niche, we suspect, is filled by dedicated cruising couples who are actually sailors (not dockside liveaboards), who want just enough to manage easily, and who have the wherewithal to treat themselves to a right little sea-boat.

Contact— Pacific Seacraft Corp., 1301 East Orangethorpe Ave., Fullerton, CA, 92831; 714/879-1610; www.pacificseacraft.com.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Used Boat Price History.”

A seagoing interior – without anywhere to sleep at sea? You certainly wouldn’t sleep comfortably offshore in a v- berth. Sorry, just another heavy, slow lump for the marina crowd.

There are two settee berths that fitted with lee clothes make excellent sea berths. I should know I have sailed my Dana from Texas to Plymouth England.

How did she do on your transatlantic? Did you have a passenger(s) or was this a solo excursion?

Having sailed for well over 60 years on my own, I have seldom encountered anyone who actually slept in their vee berths while underway. Usually in a small yacht, it is the main salon’s settees that are used for passageway sleeping with the vee berth employed as a ‘garage’ for storage.