Over the past few years, we’ve done a lot of reporting on chart plotters and navigation software—some pretty amazing stuff that gets only more amazing each year. You can now not only plan a course, but see where you actually are (on a screen), view photos of the area, check bottom topography, select which chart features you wish to view, and include tide, current, and weather information on your display. These advances have taken the art of navigation to an entirely new plane—one that feels, on occasion, a bit like a Nintendo game.

These all-electronic marvels do have some limitations, though. They all present their information on a small screen. Even the software packages that work through a full-size laptopcomputer can only display on a comparatively wimpy screen. Chart plotters and the “mapping” GPSs have even smaller screens. Clearly, there’s a problem in displaying enough information to be useful without cluttering the display to the point of illegibility. There are some tricks that can be—and are—used to compensate for limited screen size. Zooming into a smaller area certainly helps. With vector-based software you can “de-clutter” the screen, limiting the amount of detail that’s presented to what you need to see at a given moment.

But none of these features can provide the combination of detail and overall view that’s possible on a paper chart.

For comparison’s sake, a ChartKit chart measures 17″ x 22″—almost three times the area of what can be seen on a typical laptop monitor. The comparatively tiny screen of even a large chart plotter makes the comparison even more dramatic.

Some other problems with all-electronic navigation include loss of visibility in bright sunlight and the cost of additional digitized charts. Then, of course, electronics can—and do—fail. Batteries die, connections corrode, and Murphy’s Law prevails, leaving you (if you haven’t been paying attention or keeping a DR plot on the side) with no idea of where you are or where you’re supposed to be headed. And while every instruction booklet states that its software or its device doesn’t replace paper charts, the fact is that all too many sailors pay no attention to this caution.

We love computers and fancy gadgetry as much as the next technophiles. There are times, however, when it pays to pause for a moment or two and consider whether the latest technology is the most appropriate one. In the midst of just such a pause, we reminded ourselves of an approach to electronic navigation aids that has some notable advantages (and some limitations) when compared to chart plotters and computer software. The Yeoman isn’t a new invention—it’s been around in one form or another since 1985, and the latest enhancement (a version that interfaces with radar and allows integration of radar, GPS, and Yeoman plotting features) was introduced in 1999. By most computer standards, that makes it virtually prehistoric. It worked well when first introduced, though, and it works well now.

How It Works

Unlike chart plotters and computers with navigation software, the Yeoman uses standard paper charts and doesn’t depend on stored digitized charts. In fact, you can consider the Yeoman as an electronic shortcut to conventional, old-fashioned chart/parallel rules/divider navigation.

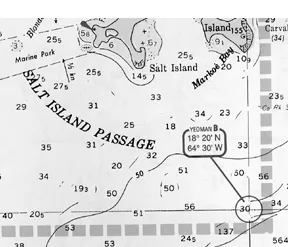

The heart of the Yeoman system is a “digitizing pad,” which is essentially a map board that contains an electronic grid. There’s also a mouse, or puck, that sends a magnetic signal to the map board. When you position the mouse over the map board, the system converts this position into a set of digital coordinates. If you fasten a chart to the face of the map board, between the electrionic grid and the mouse, and then provide the system with the information required to calibrate the chart with the board, the mouse’s cross-hair position will correspond to a precise latitude and longitude. It works with any chart with any scale.

To set up each chart, you simply position the mouse over three points on the chart to establish a latitude/longitude reference. Then enter a chart identification number and a scale. ChartKits come with marks for the three points, but the Yeoman will work on any chart for which you have defined reference points. You don’t have to re-enter these reference points each time you use a chart. The Yeoman can remember this information for up to 99 charts. (You do have to make sure that every time you change a chart, you click on the same three reference points.)

What It Does

Without a GPS connected, the Yeoman will display latitude and longitude for whatever position the mouse is centered upon. There’s a hole in the round plastic window in the mouse so that in planning a cruise you can mark waypoints on the chart (or on a clear plastic chart overlay). You can determine bearings and ranges from any point on the chart to any other as well.

When you connect a GPS to the Yeoman, the system comes into its own. You can purchase Yeoman with its own GPS built in, but there’s really no advantage over using your existing GPS. In fact, the Yeoman may well be a viable alternative to upgrading your old GPS to a newer chart-plotting model: Your GPS display function is taken over by the Yeoman/paper chart system. Once connected and when you’ve moved your mouse to a waypoint, you can download it to your GPS as well as mark the point on the chart. The Yeoman Sport XL model, the one that’s most suitable for smaller craft, is easily portable, which makes trip planning at home a simple matter—something that works with navigation software but not with a fixed-mount chart plotter. It’s also easy to carry back on the boat without having to lug a laptop computer.

Once aboard, the Yeoman lets you read out course, speed, and ETA with the click of a button. It uses an odd but fairly easy method of locating exactly where you are at any time: There are a pair of red LEDs that tell you whether the mouse is north or south of your actual position and another pair that tells you whether you’re too far east or west. When all four lights are out, your mouse marks your exact position. It’s easier than it sounds.

Miscellany

The Yeoman comes in a portable version (the Sport XL) or in a version designed for permanent installation on (or under) a chart table—the Navigator Pro. The system works when the mouse is as much as one inch away from the pad, as long as there’s no metal between the two. Both models operate on 12-volt (nominal) power supplies. They’ll run on voltages between 10 and 15 volts. Both draw a mere 250 milliamps.

Both feature a lighted mouse and can interface with a radar installation (you need an electronic compass interfaced to your radar). They work with essentially any radar that accepts waypoint information from a GPS in NEMA format.

Both models automatically correct for magnetic variation; you input the current year and the Yeoman keeps track of annual changes in variation.

Conclusions

The Yeoman system has several excellent features to recommend it. It works with the paper charts that you should carry in any case. It encourages you to keep a hard copy of all your work—essential should the electronics fail. It’s easy to read even in bright sunlight. It uses charts that let you see a relatively large area without losing detail. It doesn’t require additional panel or chart table space.

As such things go, it’s also reasonably priced—$575 is the MSRP for either the Sport XL or the Navigator Pro version. The only additional equipment required (assuming that you already have paper charts) is a GPS—unless you want to use the radar interface, which requires a radar unit and an electronic compass. It’s a fine system for on-the-water tracking.

The Yeoman doesn’t do as good a job of trip planning as do the combinations of computers and navigation software (chart plotters, usually permanently mounted on board, don’t do at-home planning at all). The Yeoman can’t deal with tides, currents, and weather, and lacks most of the frills and furbelows that are featured in many such software packages. It won’t prepare a float plan, nor handle the record keeping that’s built into the more full-featured software, nor will it present the seamless view of large areas that’s possible with some types of software.

In our opinion, an excellent, versatile navigation package might include a computer with appropriate software that would allow you to plan your cruise in comfort at home, and a Yeoman system on board to keep track of where you are and make course corrections simple. Don’t forget to mark your charts—electronics do fail at times, and in any case a US government chart is a thorough, reliable document.

Make sure that your compass is in working order, and don’t forget your dividers and parallel rules. You’re keeping those tools sharp. Right?

Contact— Weems & Plath, 214 Eastern Ave., Annapolis, MD 21403; 410/263-6700; www.weems-plath.com.