Walk down most marina docks at the start of a sailing weekend, and it’s a good bet that you’ll hear (in addition to the shouting about a bag of towels in the car, the cordless drill symphony, and the cockpit stereo in Slip 14S playing Smashmouth at Volume 11) the monotonous voice of NOAA weather radio blatting out of half a dozen VHFs.

In one boat we used to sail, the VHF, set to WX, was simply called “The Box of Lies.” Nevertheless, we must make do. The prudent mariner looks to as many sources of weather information as are available. NOAA can be OK, as long as the weather systems in question are fairly big and well defined. Local radio stations are usually a bit better. The Internet offers fabulous weather resources if you know where to look for them, and have decent access. But, in addition to all those sources, there’s you. You’re the one actually standing in the weather, and in the path of weather to come, and, believe it or not, with a little study, a handy reference or two, and a few instruments, you can become enough of a forecaster to do yourself some good.

Aside from a barometer and maybe an instrument package that gives basic wind information, most boats carry no weather monitoring and recording devices. Considering that even a few years ago it was a major investment of money, time, and space to outfit a boat with a full weather station, it’s little wonder that we rely heavily on NOAA radio broadcasts for weather predictions.

However, thanks once again to the wonders of microcircuitry, we can now literally carry weather stations in the palms of our hands. And we say why not? These instruments are pretty accurate, easy to operate, and affordable. For a modest expenditure you can have a batch of basic functions like barometric pressure, temperature, humidity, windspeed, and dew point. What you do with the data you collect is the subject of basic meteorology. We can’t delve into that topic here, except to say that there are plenty of good information sources. If you consult no other authority, read Fitzroy’s Barometer Instructions, reprinted faithfully every year in the Eldridge Tide and Pilot Book. Two other time-honored sources are Instant Weather Forecasting by Alan Watts (Sheridan House Publishers) and Oceanography and Seamanship by W.G. Van Dorn (Cornell Maritime Press).

Now, let’s move on to these handheld gizmos.

What We Tested

Given the benefits of electronic chip technology and liquid crystal displays, handheld weather instruments have evolved from miniaturized anemometers (PS, October, 2000) to full-fledged weather stations. The latest generation of anemometers are palm-sized units that measure windspeed in several scales and formats, including Beaufort. They also produce current, maximum, and average windspeeds.

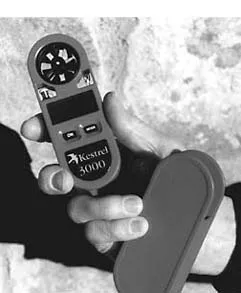

The weather stations bring several additional functions to the table, though no two stations are identical. We tested three models that have cornered the market: Brunton’s Sherpa, Speedtech Instruments’ Skymaster, and Neilsen-Kellerman’s Kestrel 3000. All three instruments carry a suggested list price of $160.

We originally included a comparable unit from Oregon Scientific, but the sample instrument we were sent produced results that were clearly flawed. In other words, it arrived busted. This model was on the European market at the time of testing; it was not available in the US. Oregon Scientific intends to introduce a US version sometime this year. Let’s hope they iron out whatever was ailing the unit we tried.

The Brunton Sherpa is manufactured in Switzerland, the Kestrel 3000 in Pennsylvania, and the Skymaster in China. All three measure windspeed in the same scales, and temperature in Centigrade or Fahrenheit, but those are the only common denominators (see chart). The newest products have reduced inaccuracies created when the instruments are not precisely oriented to the wind; manufacturers claim only 1-3% error, even when the units are 10-15 degrees off direction. We found these claims to be about right.

The Sherpa displays temperature and windspeed in round numbers, the others in tenths, but we don’t consider that a major drawback.

The Sherpa and Skymaster display current barometric pressure in millibars or inches of mercury. They also display 16 hours of barometric history in a bar graph. The Skymaster adds an excellent feature: A six -millibar change in barometric pressure within six hours produces an audible alarm. Both instruments display altitude.

The Skymaster and Kestrel 3000 add relative humidity, wind chill, dew point, and heat index to the menus. Of the additional measurements, humidity and wind chill are most important to sailors above 38 degrees latitude, and those who sail after sunset. The Sherpa is the only unit that also displays time.

Damage or wear to the impeller renders the units useless. For protection, the Skymaster swivels into a plastic case in its handle; the Kestrel 3000 slides easily into a separate case, but not as snugly as the Skymaster.

The Sherpa’s impeller is protected by rotating the impeller into its handle; however, the absence of a cover may result in scratches to its screen.

Since impellers eventually wear and produce inaccurate readings, they can be replaced in minutes.

All easily fit in the palm. The smallest of the lot is the Sherpa, which is only 3.9 inches long, 1.5 inches wide, and weighs less than two ounces. The competitors aren’t much larger: the Skymaster and the K3000 are five inches long and equally light. Of the three, the Skymaster’s screen is the largest, making it easier to read current barometric pressure and the historic graph concurrently. Buttons are large enough to be operated with a fingertip.

All three units are water-resistant to one meter, and will float if dropped overboard.

How They Operate

These models are easier to operate than a cellular telephone. Activating the Skymaster and Kestrel 3000 is as easy as tapping an “On” button; the Sherpa runs nonstop. All are powered by lithium batteries and automatically shift into barometer or sleep mode to conserve battery life when inactive for 15-30 minutes.

Scrolling to various functions is a matter of tapping a “mode” key until the desired function is reached. Weather measurements are displayed within seconds of changing modes; however, when moved from an extreme cold outdoors environment to the warmer main saloon, the Skymaster requires an hour to develop a barometric history and produce a bar graph.

How We Tested

All three manufacturers claim the accuracy of various measurements to be within 1- 3 degrees C, and provide varying levels of owner adjustments that allow units to be calibrated to local weather readings.

Assuming that most sailors will use them in their factory configurations, we did the same.

However, to produce baseline measurements, we compared their readouts to those at a NOAA station. We confirmed windspeed and barometric pressure readings on all instruments, and found them remarkably accurate. The exception was the Skymaster’s thermometer, which was 2-3 degrees F at variance with the station.

To compare their readouts, we placed them side by side in a portable Black and Decker Deskmate that provided total exposure to, or protection from, the sun. They were left outdoors for three days while we recorded measurements and changes in weather patterns. The average readings they produced were substantially similar (see chart).

It was enjoyable to watch these little gizmos perform over time. Four hours after the barometers dropped simultaneously, the weather deteriorated, and a storm appeared within hours. The next morning they presaged the coming of fairer weather.

Conclusions

The chart above shows the functions included with each unit, along with the recordings we made for six of those functions.

These little instruments shouldn’t be relied upon by themselves to provide comprehensive weather information for demanding projects like crossing oceans or launching space shuttles. However, as indicators of current conditions and predictors of changes in the weather, they appear to be as accurate as most fixed instruments mounted on boats today.

Are these instruments necessary additions to our gear list? Probably not. Are they on our wish list? You bet. They’re excellent supplements to other weather information sources. They’re easy and fun to operate, and they can help you learn about the weather. The Skymaster and Sherpa even provide bar graphs with historical changes in barometric pressure in two-hour cycles. (The Kestrel doesn’t.) They’re light, small, and self-contained—they don’t demand a big commitment of resources from the boat. And at $160, they’re just about cheap for what they provide.

Since they’re all the same price, we’d opt for the Skymaster for two reasons: it has all of the functions of the Kestrel 3000, plus a barometer with current and historic data; and the readout is larger.

The Sherpa would be our second choice; it has far fewer features than the Kestrel 3000, but includes the barometer and bar graph.

It’s harder to recommend the Kestrel 3000, if only because of its lack of a chart of past barometric readings. Without this feature, you’re forced to note a reading and the time, and then return later to see if the barometer is rising or falling.

These instruments are good adjuncts to the shiny bulkhead barometer, NOAA, and the Internet.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Handheld Weather Stations.”

Click here to view “Kestrel 4000: More Bells and Whistles.”

Click here to view “Weather Definitions.”

Contact – Kestrel, Nielsen-Kellerman Co., 104 WQ. 15th street, Chester, PA, 19013, 610/447-1555, www.nkhome.com. Speedtech Instruments, 10413 Deerfoot Drive, Great Falls, VA, 22066, 703/759-0511, www.speedtech.com. Brunton Instruments, 620 E. Monroe, Riverton, WY, 82501, 307/856-6559, www.bruntonmarine.com.