As most of us know by now, 4-stroke engines are cleaner, quieter, and more fuel-efficient than their two-stroke cousins. A 4-stroke is like an automobile engine—it carries its lubricating oil in a tank, and burns straight fuel in the cylinders. A 2-stroke engine needs oil mixed in with its fuel, and a substantial part of that oil, burned and unburned, is exhausted into the environment. The government has rightly clamped down on such pollution, and marine outboard makers are being forced to move into the 4-stroke arena in order to meet the Environmental Protection Agency’s 2006 emissions standards. The sooner the better, the lighter the better, the more fuel-efficient the better, and the more reasonably priced, the better.

With the ramp-up engineering costs long-since absorbed by the manufacturers, the price of small 4-strokes has dropped within reasonable range of same-power 2-strokes. (The same is not yet true of the bigger four-strokes, unfortunately.)

The bad news is that weight remains a major issue with the small 4-stroke outboard. Some are so heavy they don’t qualify as “portable” engines, in our view. (A 9.9, for example, carries an additional 20 pounds and considerable bulk compared to its 2-stroke counterpart.) The extra weight and size makes the 4-stroke harder to move around, and it can’t be stored as easily—it has to be stored vertically or on one specific side to prevent oil from migrating to the wrong places and damaging the engine.

Still, weighing one thing against another, the future is here, and 4-strokes are the way to go. For sailors considering which 4-stroke might be best suited to their needs, here’s a quick guide.

The Field

We rounded up data and specifications on all 4- to 9.9-horsepower 4-strokes currently on the market or slated to be released in 2003.

In total, we collected information on over 30 engines from seven manufacturers. The reality though, is that some engines built by one company are then marketed by another as their own products. This narrows the apparent choices in engines somewhat, but also gives you the option to buy the same engine from a different manufacturer for a lower cost, or from a trusted local dealer.

We looked at and gathered data on most of these small engines at boat shows or dealer showrooms and shops, and also talked with people currently using a small 4-stroke on a dinghy or tender. A few engines, however, were simply not available to us for hands-on inspections, and all data on these were supplied by the makers.

Evaluations consisted of collecting and comparing data from various sources. We did not put any of these engines on boats and run them. Instead, our goal was to build a database of small 4-strokes for the marine consumer to use when selecting an engine for a dinghy, tender or as a kicker—in other words, a “market scan.”

We chased down specifications on all engines and rated each on how easy it is to change the oil. This is an important issue, because even though you don’t have to add oil to the fuel with a 4-stroke, you do have to change the reservoir oil and filter periodically.

Portability is Key

We also looked at the portability of these engines. Which ones can a person move more easily and safely from big boat to tender and back; in and out of the station wagon, on and off the kicker bracket on the transom, and so on? Are any easier to store than others, either at home or on board? We look at this from a 4-stroke vs. 2-stoke perspective. In our view, any engine over about 60 pounds is really not very portable, unless you’re an NFL lineman or professional weightlifter.

While inspecting engines at a local marine store, one of our editors had a conversation with a local skipper who has owned and operated a 5-hp Honda 4-stroke on his inflatable for over a year. He travels, and does move the engine off and on the dinghy. He finds the engine quite heavy and unwieldy, making it difficult to transfer from boat to boat. It has nearly gone in the drink on more than one occasion, and since it’s a single-cylinder engine, it doesn’t run as smoothly as he expected.

A number of other boatowners expressed similar opinions about how heavy and cumbersome these engines are to move from boat to boat or dock to boat. We based our portability ratings on these impressions as well as our own findings in hefting these engines at shows and dealerships.

A Word On Pricing

No knowledgeable marine consumer would ever pay list price for an engine, but discount prices can vary regionally. They can also vary according to a dealer’s relationship to the manufacturer. For example, with the Bombardier Corporation (makers of Johnson and Evinrude engines), dealers who carry small engines in stock get a 10% discount on the cost of a small engine, versus non-stocking dealers. This means that you will probably be able to make your best deal on the purchase of a small Johnson engine by visiting a dealer that stocks that engine rather than from a dealer that has to order it for you. When we asked Bombardier about this policy, Senior Public Relations Coordinator, Ann Stawski responded, “As to stocking small engines, as always, consumers should consult their local Evinrude and Johnson authorized dealers for the best prices. The factory can only provide MSRP—what price the dealer sells each engine at is up to each individual dealership.”

Accordingly, in this article we’re forced to use MSRP to compare engines on a national basis.

Honda 5

Built by Honda, this single cylinder 4–stroke is the heaviest in its class at 60 lbs., and carries the highest list price as well. Its cowling lacks the curvaceous styling of its bigger siblings, and like all the engines in this review can only be stored vertically or on one specific side.

The Honda 5 has two “rests” built into the case to facilitate storage on that side of the engine. An oil change on this engine is simple, but the oil drain is located on the bottom of the engine block, which makes for oily hands when removing this plug. We’d like to see an oil drain located on the side of the engine like the plug for changing the lower unit oil. No oil filter is installed, so there’s no filter to change or clean.

Bottom Line: A little heavy and a little pricey compared to the competition.

Honda 8/9.9

This Honda two-cylinder carries either an 8 or 9.9 horsepower rating. When purchased as an 8, this engine ranks a little high on both weight and list price as compared to other 8-hp competitors. However, as a 9.9 this engine is the lightest in its class. In either hp rating the engine is quite stylish, with a smoothly rounded appearance. Like the 5, two rests are built into the case to allow for one-sided storage. We like the spin-on oil filter, but don’t like the fact that removal of an engine lower side panel is required for access to service this filter. Even though this engine is the lightest in its class when rated at 9.9 hp, at 87 pounds it’s still virtually impossible to handle over water, especially in a tippy boat. It rated poorly on portability.

Bottom Line: If you must have this much power on your inflatable, this engine, with its good looks and light weight (for its horsepower) should fit the bill. But it’s better as a transom auxiliary on a fair-sized sailboat.

Johnson 6

This Bombardier-built 4-stroke totes the heftiest list price in the 6-hp class. The Johnson 6 comes equipped with a front-mounted shifter and is available with a 15″ or 20″ shaft. For a 6, it is bulked up at 68 pounds—over our weight limit for portability. An oil change on this engine requires the removal of an engine lower side panel to access the filter.

Bottom Line: This engine is so heavy for its horsepower we would not give it serious consideration for purchase. But it’s a lot lighter than the Yamaha 6.

Johnson 8

This two-cylinder built by Bombardier ties with the Yamaha F8 for the lightest weight in the 8-hp class at 83 pounds. It is available in 15″ or 20″ shaft lengths and has a front-mounted shifter. We prefer front or tiller mounted shifters to side mount simply because it puts a critical engine control within easy reach. An oil change on the 8 requires the removal of a lower side panel to access the filter for servicing. This procedure is recommended by Johnson for each oil change, we would like to see the filter relocated to alleviate this added step.

Bottom Line: This is the most competitive engine in the Johnson line, tied for lightest and priced within $90 of the lowest.

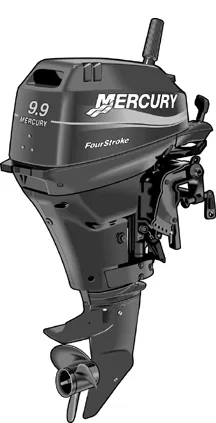

Mercury 9.9, Mercury 9.9 Bigfoot, Mercury 9.9 Sail

Mercury builds this 2-cylinder engine by combining its own lower unit with a Yamaha power head. It’s available in several standard configurations; we looked at the basic 9.9, the 9.9 Sail, and the 9.9 Bigfoot. The basic 9.9 with a 15″ shaft ranks as the least expensive in its class, with the only MSRP under $2,000. It displaces nearly 20 cubic inches and tips the scales at a hefty 111 lbs. in the basic configuration.

The Bigfoot is bulked up even more with electric start, a higher ratio gearbox, and a 20″ shaft, giving it an all-up weight of 128 lbs. The higher 2.42:1 gear ratio allows it to use a larger slower-turning prop than the basic engine, making it better suited for a larger, heavier boat. The Sail version has all the features of the Bigfoot, plus a 25″ shaft, making it the heaviest engine listed at 133 lbs. We just can’t view these engines as portable. It really is a two-person job to remove or install one of these bruisers. Service on the Mercury 9.9, however, is as easy as it gets: The oil filter is a spin-on that is accessible without removing anything except the engine hood.

Bottom Line: Although this engine is in our opinion not portable, we like the optional configurations available, each designed for specific uses.

Suzuki 4/6, Johnson 4

This single-cylinder 4-stroke built by Suzuki (new for 2003) can be purchased with a 4- or 6-hp rating. Bombardier markets the 4-hp version as the Johnson 4. All 15″ shaft versions weigh in at 55 lbs., which is manageable for the average boater. We like the 6-hp version best. It has a 50% increase in power without any increase in weight. Suzuki achieves this with a slightly larger carburetor, some engine timing changes, and a higher maximum rpm. It is available in 15″ or 20″ shaft lengths, has a side-mounted shifter, and resting pads on the port side for storage. The integral fuel tank has a capacity of just under a half-gallon. An optional external fuel tank can be added. No oil filter is installed, making an oil change a simple drain and fill.

Bottom Line: We prefer this engine in the Suzuki 6-hp configuration; it ranks among the best in class for power to weight.

Suzuki 9.9, Johnson 9.9

Suzuki’s twin-cylinder 4-stroke is marketed as the 9.9 and the 15 (not covered here). Bombardier also markets this engine as the Johnson 9.9. It’s one of the lighter 9.9s we reviewed at 97 lbs. It’s available in 15″ or 20″ shaft lengths and with or without an electric starter. Each oil change on this engine requires the removal and cleaning of the oil screen, and the change requires the removal of a lower side panel.

Bottom Line: The extra work of removing and replacing a side panel on every oil change is a hassle, and it’s difficult to know why one would buy the Johnson version over the Suzuki version—it’s priced over $500 higher. The only reason we can think of would be better dealer access.

Tohatsu, Nissan,Mercury 4/5/6

This Tohatsu-built single cylinder is marketed as nine different engines by three makers. All the 4s have integral fuel tanks and the bigger versions don’t. Tohatsu increases the horsepower from the base engine with changes to the carburetion and boosts in the maximum rpm. This engine, when marketed by Tohatsu, carries the lowest MSRP in each horsepower range it fills. In place of the pair of resting pads most engines carry, this engine lies on the tiller handle and a single pad. All weigh in at 55 lbs. with a 15″ shaft, and a 20″ shaft is also available. The oil drain plug is located on the bottom of the engine block and is not as accessible as we’d like. There’s no filter though—just a drain and fill oil change.

Bottom Line: If you can find a Tohatsu dealer in your area we think you’ll get the best price on this engine. The upside when buying from Mercury is its extensive dealer network.

Tohatsu 9.9, Nissan 9.9

The Tohatsu-built two-cylinder, also marketed as the Nissan 9.9, displaces a whopping 20 cubic inches and weighs in at an equally impressive 114 lbs., the heaviest 9.9 surveyed. It is available in 15″ and 20″ shaft lengths and is within $50 of the lowest cost 9.9 on the market—the Mercury. An oil change on the Tohatsu is a drain and fill, plus a readily accessible spin-on filter.

Bottom Line: This heavyweight lives by the racer’s credo: When you need to make horsepower there is no substitute for cubic inches. We like the price and online manuals. But unless you’re in monstrously buff shape, or have a friend around at moving time, this heavyweight is best for permanent mounting.

Yamaha 4

This single-cylinder by Yamaha is by far the lightest in its class at 48 pounds. It’s available in 15″ or 20″ shaft lengths and carries about one-third of a gallon of fuel in an integral tank. Its list price is at the upper end of the range in the four horsepower class—only the Johnson 4 is priced higher. An oil change is a simple drain and fill; no filter is installed.

Bottom Line: If your boat is particularly weight-sensitive , or you need to take the engine off frequently for racing or security, or if you have a small dinghy used strictly as a putt-putt utility boat and don’t care about speed, this would be an engine of choice.

Yamaha 6/8

Yamaha markets its newest twin cylinder 4-stroke as both a 6- and 8-hp engine. In the 6-hp class it’s a behemoth, weighing almost 30 pounds more than the lightest of the group. But, as an 8 it’s tied for lightest with the Johnson 8, at 83 lbs.

This is the latest entry in the 4-stroke field for Yamaha and sports several ergonomic improvements. The tiller handle is significantly longer than others and the shifter is on the tiller and is very close to the throttle. This allows an operator to stand up in a dinghy for better visibility and still reach the throttle with ease. It is also equipped with a freshwater flush adapter to rinse the engine of saltwater without using “ears” over the raw-water intakes.

Both versions are available with a 15″ or 20″ shaft and have an electric-start option. A high-thrust version of the 8, suitable for bigger, heavier boats is also available. It has a beefier transom bracket, a 20″ or 25″ shaft, and an increased gear ratio of 2.92:1. This enables it to use a larger, slower-turning propeller. The oil drain on this engine, which is readily accessible, is located on the lower unit. No serviceable filter is installed.

Bottom Line: We like the features added by Yamaha to improve the ergonomics of this engine. In the 8-hp class the weight is as good as currently available. As a 6-hp, it’s quite heavy.

Yamaha 9.9

The 9.9 from Yamaha doesn’t have all the recent improvements of its little brother. It is a straightforward engine available in two configurations, the standard and the high-thrust. The basic 9.9 is available in 15″ or 20″ shaft lengths with or without an electric starter and weighs in at 91 lbs. in its short-shaft version. One thing we don’t like is the side-mounted shifter. It’s the only engine in this class that still sports this design, which just isn’t as convenient as the front- or tiller-mounted shifts. Oil changing this engine requires the replacement of a spin-on filter, accessible by removing the engine’s hood.

Bottom Line: Like the Mercury 9.9, this engine is available in a geared-down version suitable for larger boats. It’s lighter than the Mercury but costs a bit more.

Conclusions

There’s no question that we should make the move to 4-stroke technology to support the environment. Thenew engines are reliable, quiet, fuel-efficient, and simple to run. You don’t have to carry a separate oil supply or go through all that tedious measuring at the gas dock. And these days the price is right, or right enough.

At least for the foreseeable future, though, a 4-stroke engine will be considerably heavier than its 2-stroke cousin, and more difficult to stow. In trying to figure out which engine to buy, consider your power-to-weight requirements. If you replace the 60-pound 2-stroke hanging on your transom with a 4-stroke that weighs 20 pounds more, what will happen to your trim? Will you still be able to muscle it on and off? Can you afford a reduction in horsepower to offset the added weight?

For dinghy power the choice becomes more complex, involving not only the weight and trim of the boat and how often you contemplate having to move the engine on and off the transom, but your intended uses of the dinghy. It’s always a balancing act. Some sailors who anchor out like to have the biggest outboard they can fit, because a 1/2-mile ride through a headwind and chop in an underpowered dinghy can be unpleasant at best and impossible at worst. Larger engines can be raised and lowered with the help of a sling rigged to a halyard-supported boom—but try it in rough water, and the idea of being able to step aboard the dink with a nice light engine in one hand becomes more appealing.

There’s also the consideration of engine repair in far-flung places. Some long-distance cruisers tell us they’ll stick with 2-strokes until outboard mechanics everywhere know how to fix the 4s, and have parts available.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Value Guide: 4-6 HP Four-Strokes.”

Click here to view “Value Guide: 8-10 HP Four-Strokes.”

Click here to view “Ratings: 4-10 HP Four-Strokes.”