Following a major financial and organizational restructuring precipitated by the boatbuilding downturn in the 1980s, a revitalized Fairport Yachts, Ltd. recently became the first big production builder to start making sailboats with only epoxy resins throughout hull lamination. Epoxy is used as a barrier coat by some production builders, and as a laminating resin by some custom builders of high-end racing and cruising boats, but Fairport is pushing these materials and techniques into the mainstream. This could be considered the most significant departure from traditional fiberglass boatbuilding methods since the introduction of vinylester resins.

Company History

Tim Jackett is the chief operating officer and designer for Fairport Marine, which builds C&C and Tartan yachts. However, except for the guidance of Jackett, there’s little resemblance between the “old” C&C and the new company.

After enduring a financial shortfall in the 1980s, Fairport emerged on the cruising side of the boatbuilding industry with newly designed Tartans. The company then purchased the remnants of C&C, primarily the brand, in the 1990s.

The C&C line has a loyal following, dating back to the days of George Cuthbertson and George Cassian, founders of that legendary Canadian boatbuilding company. However, there’s a significant difference between the last boats built by the originators and the C&C 110, which was introduced in 1999. The new line is geared to sailors for whom performance is an overriding consideration, though crew will make racing passages in relative comfort. By comparison, Tartan yachts display a turn of speed, but are more traditional cruisers.

Prior to introduction of the C&C 99 in 2001, 75 of the C&C 110s were built, and the company introduced the C&C 121, a 40-foot “performance cruiser.”

The company hit its production target of 30 of the 99s in the first year, and the run now numbers in the low 40s. Jackett says the company’s combined annual production is 70 boats. It has a stable work force, and has made a significant investment in equipment required to convert to epoxy construction methods. All seems to bode well for an outfit that has gritted its way through the best and worst of boatbuilding economics over the years.

Design

Jackett has been designing sailboats for Tartan since the mid-1980s. His versatile designs reflect the delineation between two niche markets, and he’s inclined to introduce features in boats not found in the mainstream production world—an electric swim platform concealed in the stern of the 110, for instance.

Of the C&C 99 design he says, “I built the boat for guys like me—a guy in his mid-40s with kids who wants to go fast, who likes to look sporty, and likes to go on a picnic sail with his wife. It was designed to function as a light-displacement racer-cruiser that doesn’t need a lot of weight on the rail to be competitive.”

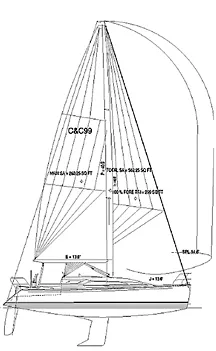

She has a plumb bow and reverse stern, similar to her predecessors. Viewed from the bow she displays a rounded cabin shape and wide decks that offset her beaminess. Other elements are a relatively flat sheer, and modest freeboard. Beneath the surface, her canoe body has low wetted surface and carries a long, flat run aft.

Her SA/D is 23.4, virtually identical to that of the 110 and 121 (the 121 is 23.2). This number indicates a lot of sail power in all three boats. The D/L of the 99 is 167, compared to a D/L of 156 for the 110, and 141 for the 121. These numbers, too, point toward performance—not flat-out, but at the higher end of the scale for any boat with reasonable provisions for sleeping and eating comfort.

Jackett has resisted the temptation to equip any of these boats with more than one head. The head in the 99 is forward to port; it is aft in the other models.

The aft cabin arrangement of all three boats is different, as well. Pillows in the 99 are outboard to port, and the berth is set at an angle. The berth on the 110 is outboard to starboard, and less accessible. The stern in the 121 is large enough to orient the aft berth on the centerline.

Construction

As mentioned earlier, these C&C boats are made with epoxy. This is a big move in the production boat world.

Historically, a typical lamination schedule has consisted of a layer of gelcoat and layers of strand and mat fiberglass impregnated with polyester resin (lower resistance to osmotic blistering) or vinylester resin (higher resistance) on the inner skins. Epoxy offers the highest resistance of all, as well as very high strength for its weight. However, it’s also the most expensive, and is best cured at a fairly high temperature in a big oven (autoclave). It’s not the easiest material to work with.

A characteristic of most gelcoat is that it bonds easily to polyester. The introduction of epoxy on an inner layer to a polyester gelcoat can be akin to attempting to mix oil and water; over time, the bond can fail and the structure delaminate.

Jackett’s new lamination schedule calls for a coat of Ferro Ultra-Shield NPG/ISO gelcoat, which has some of the same chemical properties as epoxy. That coat is bonded to a vacuum-bagged, wet-impregnated epoxy laminate with uni-directional E- glass. The use of epoxy resins eliminates chopped strand mat, which Jackett considers the cheapest, heaviest, and weakest component used in conventional polyester hull construction.

The hull is cored below the waterline with Corecell closed-cell linear polymer foam, and above the waterline with Baltek AL-600 end-grain balsa. The combination provides stiffness and strength without dramatically increasing weight. The keel laminate is reinforced with multiple plies of high-tensile carbon fiber.

Since the company has not had problems with osmotic blistering since 1985, water resistance was not the prime motivator in the decision to make the change to epoxy. Jackett cites epoxy’s strength and light weight as two of its most beneficial characteristics.

“We employed two manufacturing methods,” he says. “We initially used a gelcoat bonded to a conversion layer, referred to as a tiecoat, that allows epoxy to bond to a polyester gelcoat.” The first 50 boats successfully employed this process.

In that process, halves of the hull are constructed and vacuum-bagged separately. However, a cosmetic problem occurred: “The tie coat was contributing to postcure print that required additional labor to correct, and the conversion layer doubled the gelcoat. The tiecoat also has a limited lamination window, unnecessarily complicating the lamination process.”

The company moved to Plan B, with the application of a modified epoxy skin coat. “Through testing we have developed the proper surface prep prior to application of the epoxy laminate,” says Jackett. The result is a proper bond with no print-through.

In the next step, a stitched, unidirectional fiber cloth is rolled through an impregnator calibrated to produce specific resin content. Since epoxy is sensitive to resin-hardener ratios, the company invested in machinery that produces mixes in exact proportions.

“These boats now have 67-70% glass content, versus old boats that typically had a higher resin content,” he says.

Workers now have more time to install the interior structure of the boat. “A typical process might allow a builder to add two to three layers of laminate per day,” said Jackett. This could extend the layup process for days. “With this system, the vacuum bagging takes only 20 hours, during which time the resin reaches 60% of its ‘sizzle property.'”

Both halves of the hull are then moved into an oven for 24 hours, during which the temperature is raised from ambient to 145° F. Heat is ratcheted up to specific levels and held for various periods of time to allow the resin to cure. The gradual process prevents thermal shock that could eventually produce lamination failures. The hull is then gradually cooled before being removed from the oven.

Of the process, Jackett says the weight of the skin laminate has been reduced by 50%, but strengthened by the increase in fibers.

The weight of the shell of the C&C 99 constructed with polyester resin would be 1,600 -1,800 lbs. With epoxy, it’s 780 lbs. In tests of laminates prior to making the conversion, the company discovered that a laminated polyester section consisting of several layers of material would fail at a joint under 600 to 750 lbs. of pressure. In testing the new system, they discovered that the laminate, not the joint, separated when pressure was between 2,300 and 2,700 lbs.

Reinforcements are made at through-hulls, the keel, and other high- load areas where the thickness of the epoxy is sufficient for loads, but too flexible.

Aside from the issues of weight and strength, Jackett says that epoxy also has better cyclic loading characteristics. “A problem with polyester is that in high-load areas, micro-cracks may appear over time because polyester will lose as much as 50% of its strength in its first year. With epoxy, the loss is only 5%.”

We asked Joe Parker, a technical advisor at Gougeon Brothers, Inc.,developers of the West System epoxy products and leaders in the field, forhis opinion of Jackett’s methods.

“Using epoxy resins to build boats can provide significant benefits to the boat owner,” said Parker. “While proper design, engineering, and manufacturing processes are crucial to maximizing those benefits, a quality-conscious builder like Fairport can be very successful in this transition.”

It’s a measure of Fairport’s confidence in epoxy that they offer a 15-year guarantee on these boats.

So, why don’t more builders go this way? The process requires an investment in equipment, and higher material and labor costs. The C&C 99, for example, costs about the same as a “normal” production 36-footer.

Deck and Rig

The deck layout and cockpit of the 99 reflect a no-nonsense approach to maximizing performance, whether in race mode, or cruising.

The deck is constructed of a composite laminate with unidirectional E-glass skins and Baltek AL600 coring. High-load areas and the locations of hardware installation are reinforced with additional layers of laminate and sealed to prevent the intrusion of water. The hull-deck joint is secured with stainless machine screws installed on 4″ centers through a 6061 T6 aluminum backing plate imbedded in the hull flange, a method that meets ABS requirements for offshore yachts. The joint is sealed with 3M 5200.

A black powder-coated double- spreader mast is equipped with tapered airfoil swept spreaders supported by 1×19 stainless steel wire rigging. The stainless steel chainplate system ties to an internal fiberglass structure that is reinforced in the hull skin.

Halyards are internal, led aft to rope clutches and Harken 32 self- tailing winches on the cabintop. Ports on the bulkhead provide ventilation and a convenient place to stow halyard ends belowdecks when sailing, reducing clutter in the cockpit.

The boom is equipped with single-line slab reefing and an internal 4:1 outhaul led aft to a cabintop winch.

The most prominent feature of the U-shaped cockpit is a 40″ destroyer-type wheel. The removable helm seat is reinforced with carbon fiber and supported by a gas shock when tilted upward, to allow passengers to enter from the stern. The helmsman has a clear sightline to instruments mounted on a pod at the companionway whether seated or standing, as does the cockpit crew. The pod is pre-wired for the installation of additional units.

The mainsheet is attached near the end of the boom and on a traveler near the helmsman’s fingertips. A Harken fine-tune mainsheet system and double- ended backstay adjuster with a 40:1 ratio allow for one-handed mainsail trimming and tensioning the headstay—a real plus when the wind pipes up. Jib sheets are led to Harken track and ball-bearing genoa cars. The primary winches are Harken 44 self-tailers.

The cockpit is smallish, suitable for seating four guests, or two trimmers when in race mode. The coaming is high enough to provide back support. Decks are wide and flat, allowing easy movement forward, and fairly humane seating for rail riders.

A Lewmar Ocean Series size 60 aluminum foredeck hatch and Ocean Series size 30 atop the cabin provide ventilation.

Belowdecks

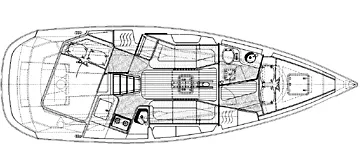

To a die-hard racer, the spaces belowdecks will seem plush. To a comfy cruiser type, they’ll seem a bit spartan. There’s 6′ 2″ headroom, a big plus on a 32-footer. The nav station, settee, and head are to port, C – shaped galley and settee to starboard. Jackett borrowed one design feature from the Tartan 31; when the head door is open, it conceals the toilet and sink while increasing visual space. Access to the aft stateroom is to port. Water and holding tanks are beneath the forward berth, fuel below the port settee.

Wood joinery is nicely finished cherry with a satin finish accented by a teak and holly sole, white fiberglass headliner with wood battens, and low- profile fixed portlights running the length of the saloon that produce a tunnel-like affect.

Ventilated solid stock varnished cherry panel locker doors are mounted in laminated cherry door frames and equipped with push-button latch sets that function well in a seaway.

However, cabinets and trim are varnished cherry cored with ITW SprayCore, a foam that reduces weight without compromising strength, since the doors aren’t load- bearing surfaces.

The galley is equipped with a two-burner gimbaled propane cook top surrounded by a molded Granicote solid surface. Lighter than Corian and as strong and durable as a composite, Granicote is becoming more common in the industry. A molded icebox is insulated with 4″ foam.

The master stateroom has an oversized V-berth large enough for two adults, and is furnished with a hanging locker and shelves running the length of the hull. The berth in the aft stateroom is a double; storage is below the berth. Orienting the berth forward allowed the builder to place a propane locker outside and a lazarette in the starboard corner of the cockpit.

We’ve been aboard three 99s constructed during different production runs, and consider fit and finish of the interiors to be well executed.

Performance

We had hard luck in our several attempts to test the 99. On one occasion a nor’easter with 35-40 knots winds kept us at the dock. On another, we endured four hours of windless drifting, waiting for wind to appear. As a consequence, and allowing leeway for their bias, we’ll rely for now on the owner comments for an indication of performance.

Pricing

The base boat is priced at $117,900, a $3,000 increase since its introduction, whether fitted with a deep keel or the standard fin. Factory spinnaker gear adds $3,000, and a Raymarine ST60 Tridata & AWI package $3,200. Prices are FOB Fairport, Ohio.

Conclusion

The C&C line adds a valuable dimension to the American sailboat industry by introducing boats targeted to the sailor who seeks a bit of extra performance but may not want a totally dedicated racer like the Mumm 30. Since Tim Jackett also designs the Tartans, he brings creature comforts to the C&C line without compromising on the primary objective.

The introduction of epoxy bodes well for owners who are willing to spend extra dollars for boats that, over the long term, should maintain performance levels, durability, and resale value.

Fairport Yachts, Ltd.

440/354-3111

www.c-cyachts.com