Trying to pin down the technology, trade names, and jargon that define contemporary sailmaking is more than daunting—but it must be done once in a while, even if accuracy is fleeting. PS checked in with representatives from the major sailmaking labels in the U.S. to see what’s available these days for recreational and cruising sailors. (We’ll speak here only of mainsail and upwind headsails, not spinnakers.)

The companies that make and market sails usually segment their consumers (and thus their products) into two general realms—racing and cruising—with the former normally garnering the lion’s share of R&D resources as well as the marketing muscle. This situation, however, appears to be in flux as more sailmakers are acknowledging the existence of a vital market among cruising, or less racing-oriented sailboat owners. That’s great news for the non-racing sailor, as these companies attempt to arrive at innovative approaches for sails that hold their shape longer and offer good performance along with a broad range of adjustability.

What’s important about good sail shape? As one sailmaker likes to explain it, using poorly shaped or blown- out sails is like driving on bald tires. You’re pretty sure your car will take you from A to B, but you won’t be able to turn well or stop promptly, and your enjoyment of driving will be diminished.

Before wading into these complex waters, it’s good to know some essential terminology and understand a few basic concepts involved in sailmaking, so here’s a quick primer.

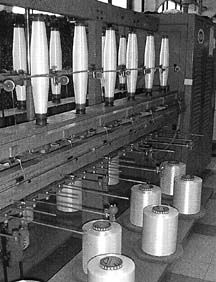

Upwind sails are characteristically built in two ways, either by crosscut or composite construction (often referred to as laminated sails). Crosscut sails are essentially built of woven polyester fabric (most often known by DuPont’s trademarked name, Dacron) where the panels of cloth run from the luff of the sail to the leech. Composite construction can be achieved in several ways, but the objective is to align the load-bearing fibers of the main structural material (often referred to as the scrim) with the primary load paths of the sail. Doing this requires layering different materials, since mere woven polyester, with its strength primarily in the fill (or short axis) direction of the weave, won’t suffice for more than modest loads and thus isn’t sufficient in composite construction for sails that will be hoisted on boats over 20 feet.

Regardless of the sail or sails you consider, don’t just nod when a sales person tells you what’s best for your boat—get them to tell you why it is that he or she is specifying a particular material or construction method, and you’ll ultimately have a greater sense of satisfaction regarding the product you purchase. Now for the overview.

North Sails

Often seen as the industry’s 800-pound gorilla, North Sails offers an extensive range of products and services through its franchise system, with a network of 40 loft facilities in Canada, the US, and the Caribbean alone. This company markets no less than seven products targeted at recreational and cruising-oriented sailors, ranging from the proprietary NorDac 4800 series of mainsails and genoas to the high-tech Marathon 3DL laminated sails.

According to Dan Neri, who manages North’s cruising sail development in Portsmouth, R.I., in-house research has brought about some important advances. “It used to be that the least expensive sails were more durable, but not equal in performance to the more expensive sails,” he says. “Now almost all sailcloth products essentially give you equal durability, but they don’t give you equal shape-holding ability, and that’s the big difference.” In general terms, says Neri, the more you spend now, the better shape holding you’re going to get.

North builds its least costly sails out of NorDac 4800, a material woven from Dacron fibers that the company buys from several sources and then sends to a mill, specifying the parameters of the weave to create a proprietary product. NorDac 4800—available in weights from four ounces to nine ounces (per square yard) —is used to build mainsails and headsails. Though it’s advertised as “tightly woven cloth,” the weave isn’t as tight as that in the company’s next step up—Premium NorDac. The latter is woven from “high-tenacity” Dacron, which means it will stretch less than the fibers used for NorDac 4800. This ultimately translates into longer shape retention. North promotes this cloth as the most tightly woven Dacron fabric in the world.

Neri explains that the polyester fabric used to make most cruising sails these days is impregnated with resin. With a more tightly woven fabric you don’t have to use as much resin. A less expensive cloth gets most of its bias strength (resistance to stretch on a diagonal) from the resin, whereas the more expensive cloth derives more of its strength from the weave.

The next step up is a laminated fabric the company calls Soft NorLam, which is assembled with a Mylar film in the middle of two woven Dacron layers. This is where the oriented construction begins within North’s product line. For larger boats the company offers a range of fabrics using woven Spectra layers laminated on both sides of the Mylar film. (Spectra is a polyethylene fiber produced by Allied-Signal. It has tremendous initial resistance to stretch, but does elongate over time with constant stress.)

All the cloth used in North’s composite sails is woven at a facility the company owns in Connecticut, then sent out to be finished. For shape holding, says Neri, NorLam is superior to the best Dacron products, as it doesn’t have the resin in it to break down. North pushes this cloth for many of its recreational or short-distance cruising customers, he says, because it can be rendered lighter than Dacron for that same application, and retains its shape so much better than other cloth.

For roller-furling headsails, North markets a Soft NorLam sail it calls the RF2, which it says is especially suited to this application because stronger fabric is concentrated in the leech and the foot areas, using panels of varying weights.

The lightest NorLam cloth uses 5-oz. Dacron laminated to Mylar. The heaviest uses 10 oz. of woven Spectra or Spectra and carbon for megayacht applications. According to Neri, NorLam has a big advantage over Dacron panels because it stays relatively stable on the bias until it ultimately yields, while Dacron used without any additional structure will distort gradually over time.

“Longevity is totally dependent upon how the boat is used and where,” he explains. “We’ve found that customers who really work their sails get about four years out of laminated sails, and at the end of that period the sails are essentially shot. If the same customer had Dacron crosscut sails he could milk those sails for roughly seven years. The big difference is that at the end of three or four months with the Dacron sails you’ll have the same shape that the Norlam sails will have at the end of about three years. That’s essentially why sailboat owners who make the move to composite sails just don’t go back to Dacron.”

The higher-end headsails and mainsails offered by North—specifically for long-distance cruising sailors who value sail shape and performance—include the company’s trademarked Spectra/Dyneema material, used when light weight and low stretch are the prime considerations, and Marathon 3DL, North’s marquee product for high-end cruising inventories.

Many sailors are familiar with North’s 3DL process, in which laminated sails are built on a large mold with yarns laid out and sandwiched in between layers of film to carry the primary loads. Neri says that a Marathon 3DL sail is basically a 3DL sail sandwiched between Dacron covers on each side. The sails are protected, says Neri, by their oversize yarns. “Even if the sun breaks down all the UV inhibitors and blockers we use, and cooks the outside of the yarn, the core of the yarn retains its strength.” He explains that the largest yarns used in woven Dacron sails are 500 deniers (a measurement used to specify the weight of a yarn). The yarn used in a 3DL sail is a 1,700 denier yarn, “which is really why these sails don’t rot or break.”

For the strength in its 3DL sails, North primarily uses Vectran yarns, which Neri admits doesn’t have the best resistance to UV degradation, but holds up because of its size.

The outer layers of Marathon 3DL sails are made of a proprietary product North calls TF, which is a customized 1.7-ounce NorLam taffeta/film developed expressly for this application. Neri says that the TF film not only protects the internal fiber matrix of the sail from chafe, puncture, and UV degradation, but combats off-axis stretch and contains double the usual amount of titanium dioxide UV screening agents, plus a fungicide to discourage mildew growth.

Neri admits that the Marathon 3DL sails are more expensive, perhaps by 30 percent, but he offers the following perspective on that issue: “It seems like misplaced economy to save whatever the difference is by buying a Dacron sail and have what turns out to be a poorly shaped airfoil for most of the sail’s life. When you weigh that gain against the total amount of money you spend to enjoy your boat, you might as well have a sail that retains its shape and consequently makes the boat faster, makes it not heel over as much, and is easier to hoist, reef, and douse.”

Quantum Sailmakers

Dave Flynn, a salesman and sail consultant at Quantum’s headquarters in Annapolis, MD, is keen to distinguish his company as a custom sailmaker. “Quantum builds sails for a very broad spectrum of clients,” says Flynn. “We build everything from grand prix sails to Optimist sails. In general we build engineering-intensive products that are high quality, and we tend to attract customers who are a little more demanding due to custom issues.”

Now entering its eighth year, Quantum is a young sailmaking company. Roughly 50 to 60 percent of the sails this company builds are crosscut Dacron, which, as Flynn points out, is still a relatively cost-effective way to fabricate sails. But Quantum’s specialty is composite-built sails.

“Cruising sailors in general hate to hear the word ‘performance,'” says Flynn, “because it denotes racing. But performance is really important for cruisers because it’s about good sail shapes that offer better control of the boat. For Quantum, that’s where better materials and stronger, less stretchy sail construction comes in.” Flynn says that both composite and crosscut construction will produce sails that last long, roughly 3,500 hours, “but composite sails have a longer life as a critical airfoil…in rough terms you gain probably two to three times in the shape life of a sail by going with composite construction.”

According to Flynn, all composite sails are made using the same basic structure—large oriented fibers that do most of the work and a piece of Mylar film sandwiched between two woven layers of cloth. “Many cruising boat owners have a hard time accepting Mylar, but Mylar is nothing more than polyester extruded in a sheet. The reason to use it is that it is equally strong in all directions. When you take this film and stick it in a composite laminate, you achieve bias stability.” What really differentiates one product from another in the market, says Flynn, is the structure inside the laminate.

For its cruising customers, Quantum offers three choices of structural yarns in the composite sails it builds: Polyester, Spectra, and Vectran. The lower end in terms of cost begins with Dacron fibers, which Flynn says can be used in composite applications to render sails that are slightly lighter than a comparable crosscut sail. These sails have the same flex and UV resistance as their crosscut cousins, but hold their shape much longer. Another polyester option is Pentex, a high-modulus yarn that has no greater flex, UV resistance, or durability than Dacron, but stretches two to three times less. According to Flynn, Dacron works well for smaller, lighter weight boats, Pentex yarns work well in sails on boats up to 45 feet, and after that customers are encouraged to buy sails built with Spectra, Vectran, or even carbon yarns.

Spectra is what Quantum recommends for high-load applications where performance and durability are required and cost is less of a concern. Spectra, however, is quite expensive, says Flynn, particularly in scrim form, and it does have two other drawbacks: it is subject to creep (it elongates under constant load) and laminates built with this fiber are particularly susceptible to mildew.

Vectran—a polyester-based liquid crystal fiber manufactured by Hoechst-Celanese—is heavier than Spectra, yet offers five times the stretch resistance of polyester. It also has great flex characteristics, but is more expensive and more prone to UV degradation than Spectra. It is also slightly heavier, so Quantum recommends Vectran in applications where weight is less of a concern.

Flynn says that Quantum will specify varying weights of the woven Dacron taffeta—the bread in the composite construction sandwich—depending upon the application (mainsail, headsail, etc.). Because any laminated sail is susceptible to moisture penetration, these layers are usually treated with an antifungicide to combat mildew. Quantum obtains this cloth from a variety of suppliers. “We do our own testing and analysis of sailcloth,” explains Flynn, “and we buy accordingly.” He says the company customarily purchases Dacron from Challenge Sailcloth, Bainbridge International, and Contender. “The reality in this industry is that cruising sailors are the ones who more often than not get stuck with the low end of any product line, because the perception is that they don’t know any better. And it’s almost impossible to tell the difference between a good, a mediocre, or a poor quality fabric unless you test it. So we differ from other sailmakers in that we only use the best materials. We don’t use any of the low-end fabrics.” This policy, Flynn admits, occasionally means Quantum’s products carry a higher price tag.

UK Sailmakers

In business for almost 50 years, UK Sailmakers offers sails for nearly every facet of the sailboat market, but UK International’s general manager, Adam Loory, hastens to point out that the company prides itself on its custom sailmaking. “All our sails are custom- designed and custom-made for each customer. We don’t have off-the-shelf products, and we use our own proprietary design program to complement that service.” Yes, the company does have a franchise with a loft in Hong Kong that builds custom and OEM sails, says Loory, “but you can’t compare the OEM sails to the custom sails they or any other UK loft builds.” For the non-OEM sails, he explains, every prospective customer is asked nine essential questions about his boat and the kind of sailing he or she does. “Then you have to measure the boat so that whatever you design fits all the specifics of that particular boat. Sails really can’t be stock items. They have to be custom.”

Within UK Sailmakers’ worldwide group of nearly 40 lofts and sales offices, half of which are in the US, some franchisees cater to cruising sailors and some to racing sailors, simply as a factor of the given local market. Every loft can build woven Dacron crosscut sails, which make up the majority of the company’s cruising orders, but they can also create sails using a patented construction process that UK Sailmakers markets under the name Tape-Drive. “This is essentially a two-part construction process,” explains Loory, “where the skin that defines the sail shape is a separate element from the part of the sail that gives it strength and shape-holding ability.” He offers an analogy from the construction industry where “a traditional sail is sort of like a masonry construction process in which the walls define the shape and hold up the building. With Tape-Drive, it’s more like a modern office building where the structure is derived from a steel skeleton and the shape is provided by the glass curtain of walls.

“The idea behind the tapes is to have them oriented so that they run continuously between the three corners of the sail to handle the primary loads. On a 30- to 40-foot sailboat you’ll have anywhere from 30 to 60 tapes on a leech of the sail, which is a lot of structure. And most of the tapes we use have a breaking strength of around 1,000 pounds.

“The huge advantage for the cruising sailor,” continues Loory, “is that the Tape-Drive grid keeps any damage localized. If you get a minor problem with your sail while you’re out sailing—like a spreader tip poking through it—you can keep sailing without fear of the sail ripping.”

Loory explains that UK has been refining its Tape-Drive sails since the first one was built in 1984. He says that the Tape-Drive system offers UK Sailmakers a lot of flexibility regarding the materials used. “We can match the materials to the budget and performance demands of a customer. We can make a Tape-Drive sail with a polyester laminate or a Kevlar laminate, both of which are less expensive than Spectra. And the tapes can be reinforced with Kevlar, carbon, Pentex, or fiberglass yarns.”

According to Loory, the company buys its laminate materials and Dacron from Dimension Polyant, Bainbridge International, and Challenge Sailcloth. Some of the tapes it uses are actually fabricated at UK lofts. “We make a point of staying on top of the research and design issues, so we give the supply companies a little competition this way.”

To cater to the cruising market, UK Sailmakers produces what it calls a Passagemaker genoa in two different constructions—Dacron and Tape-Drive. Each incorporates roller-furling with a UV cover, foam luff, reefing reinforcements on the foot and leech, and each is fitted with marks aft of the tack so that the user can achieve the proper settings when furled. “For roller-furling sails we make our UV covers sacrificial. They’re put on last and they even cover the webbing for the rings. This makes the cover easier to service and replace once it wears out.”

Again for the cruising market, UK Sailmakers offers a mainsail it has dubbed the Batmain. These sails are also designed and built in either crosscut or Tape-Drive configurations with full-length battens, which Loory says offers three important advantages: the sail holds its shape more easily, it lasts longer, and it’s easier for the user to handle. He also points out that full-battened mainsails tend not to slat when a boat rolls in light air and large waves, and they offer better projected area downwind by supporting the leech of the sail. The company also builds roller-furling mainsails.

UK Sailmakers’ most advanced cruising sails are called Platinum-Drive sails, made of a Spectra laminate with Kevlar or carbon fiber tapes in the Tape-Drive configuration.

Hood Sailmakers

If there’s one company among the larger sailmaking firms that is truly invested in the non-racing realm, it’s Hood Sailmakers. Headquartered in Middletown, R.I., Hood is distinguished in a number of important ways. First, this is the only company that has eschewed laminated sail construction, and it is one of the few companies that creates its own sailcloth, which it has since the early ’60s.

Tim Woodhouse, president of Hood Sails, says his main focus, and the main thrust of the company’s R&D, resides in two areas—woven polyester and Vectran. “As other sailmakers began moving into laminates several years ago, we went the other way,” he says. “We found that we couldn’t offer customers anything approaching a three-year warranty with laminated products, no matter what adhesive we used—and we’re talking about a sail that would be roller-reefed. To me, that’s just unacceptable”

Woodhouse explains that the company’s cloth manufacturing division—Hood Textiles, located in Cork, Ireland—creates a fairly narrow range of fabric intended for use in durable, longer-lasting cruising sails. “Our facility manufactures a full line of woven, high-tenacity polyester sailcloth, which we only sell within our franchise system.”

Woodhouse says that many sail- buying customers don’t realize that there are three qualities of polyester fiber available for weaving sailcloth—low, medium and high-tenacity. “Consumers and a lot of experienced sailors don’t know this,” says Woodhouse, “but there is a substantial difference in the quality, durability, and stretch resistance of the fabric, depending upon what level of fiber it’s been made of.” He claims that the vast majority of polyester fibers on the market today are low-tenacity, and says that Hood only makes products from high-tenacity polyester.

“We also make a proprietary product that incorporates Vectran, which we call Vektron—it’s essentially Vectran yarns commingled with the polyester.”

Woodhouse labels Vektron a successful alternative to laminates. “It has significantly longer life than a laminate. It has the same longevity as a Dacron, but it is lighter and lower stretch than Dacron.” One key advantage of incorporating Vectran, he says, comes from the material’s high resistance to heat, which keeps it from distorting when the polyester into which it’s woven is heated in the finishing process that almost all sailcloth is subjected to.

But saving weight and maintaining durability, says Woodhouse, is Vektron’s chief advantage, particularly when it comes to sails built for larger vessels. Hood recently built a new Vektron mainsail for the 130-foot J-Class yacht Endeavour. It ended up almost 50% lighter than the boat’s previous mainsail. “For a more common boat, say one that displaces 15,000 to 20,000 pounds, we’d probably specify 9-ounce Dacron for sails, but in Vektron we would use a 7.7-ounce material. Of course this would be for a guy who wants to go world cruising, and he’d get about 30,000 to 40,000 miles out of either sail with routine maintenance in stitching and seams.”

Woodhouse says the original Vektron sails that Hood built back in 1992 are still being used. “We’ve had no instances of the fabric failing. Very few people have put in that number of hours on laminated sails and are still using them.”

Woodhouse allows that a Vektron sail is roughly 15% more expensive than the Dacron alternative that his company would build. Nevertheless, Vektron products make up half the sails Hood now builds.

Not all the lofts in the Hood franchise system follow Woodhouse’s philosophy regarding woven fabric sails vs. laminate sails. “Some of our lofts have a greater percentage of racing clients, so they’re working with laminates in the dinghy and one-design areas,” he says. Those lofts are free to purchase sailcloth through the four main industry suppliers (Bainbridge International, Dimension Polyant, Challenger Sailcloth, and Contender), a factor Woodhouse believes offers them flexibility in the marketplace. Nonetheless, his opinion remains the same: “When you start asking customers what their expectations are for the longevity of a sail, some of them haven’t thought about it. Racing customers in particular have become accustomed to diminished expectations in this regard. They speak in terms of hours, not days. Unfortunately, the longevity of racing sails has gone down, not up, with new laminate technology. Our products are addressing through R&D what the average sailor out there wants and needs, and to me that’s better performing, more durable sailcloth. I just don’t think we can get there with laminates.”

Neil Pryde Sails

The name Neil Pryde might draw more recognition as a maker of windsurfing sails and an OEM supplier, but the company is also a strong player in the custom cruising and recreational sailboat market. According to Managing Director Tim Yourieff, who operates out of the US corporate headquarters in Milford, CT, “most of our sails are built for cruising boats. Our true niche is really performance cruising.”

Making the transition from being solely a mass producer of sails for boat builders to a custom sailmaker required that the company retool its approach to sales and production, which Yourieff says included developing a renewed understanding of the importance of communication with the user. “We clearly delineate the type of products we offer so that we can direct the customer to the sail that’s suitable for their application.”

This philosophy led to the four distinct lines of sails offered by Neil Pryde Sails: Performance Cruise, Cruise Plus, and Cruise, as well as sails designed and built expressly for less demanding, recreational boats, called Inshore sails.

The majority of Neil Pryde sails are cut and assembled at its massive facility in China, which company literature touts as “the largest centralized sail loft in the world.” Yourieff explains that this helps his company maintain the highest construction standards possible. “We’re able to put a lot of detail in the sails because we manufacture them in a central facility.”

However, all the design work is done in the US, and all materials originate here as well. To interact with and service its customers, Neil Pryde Sails has a system of 30 lofts worldwide, all of which are sales centers and some of which are service lofts.

The company’s entry-level product—the Inshore line—says Yourieff, is for weekenders or daysailors, but essentially not for boats over 25 feet. These sails are ordinarily single-ply, crosscut Dacron sails of up to 6.5-oz. cloth, with plastic headboards, a single row of stitching, and no frills. “We get our Dacron from Challenge Sailcloth and from Contender,” he says, “and we don’t cut corners on the fabric—it’s all high-tenacity Dacron.”

The next step up for cruising or non-racing customers is the Cruise line, which also means crosscut Dacron sails (built of either Challenge’s High Modulus or Contender’s Super Cruise fabrics) that the company advertises as “inshore cruising sails designed to handle additional offshore use as well.” These sails are single-ply panels reinforced in the highest load areas with “block” patches (not radial). They also have heavy-gauge aluminum headboards with stainless steel liners and hand-sewn slugs.

Then, by opting for what the company calls its Tradewinds specifications, customers can get what charterboat clients get—heavy reinforcements on almost every aspect of the cloth, stitching, and hardware. Yourieff labels these “truly the best value cruising sails on the market today… We’ve had guys do circumnavigations with the Cruise-level sails. I wouldn’t recommend that specifically, but they’re good sails.”

After that comes the Cruise Plus line, which are also crosscut Dacron sails. “The biggest difference here,” explains Yourieff, “is that we two-ply the leech and the head and all the reinforcements are radial. And the sail numbers and insignias are included in the price.” These sails, he says, are really intended for the blue- water sailor.

Though the Cruise Plus sails have many standard features, the rollerfurling headsails in this line don’t come standard with foam luffs or UV-resistant sail covers. Like all the company’s sail products, these carry a two-year warranty for work and materials.

Neil Pryde’s top-of-the line sails for cruising customers are built as Performance Cruise sails. These are laminated, tri-radial sails, and it’s in this realm where the customer choices are the broadest. These sails are generally sandwiched inside a Dacron taffeta, though occasionally the taffeta is just on one side. This is intended to protect the scrim fibers and the film from abrasion and UV degradation. Yourieff points out that customers have a number of choices regarding the fabric—polyester, Pentex, or Spectra.

Halsey Lidgard

Paul van Dyk, the special projects manager at Halsey Lidgard Sailmakers in Mystic, CT says boats in the 30- to 60-foot range comprise his company’s core market. “We occasionally make sails for smaller one-designs, and we’ve definitely developed a specialty as a sailmaker for megayachts (including sails for PlayStation and Team Adventure), but our principal customers own midsize boats.”

Regardless of the nature of the boat, van Dyk explains that the constant that links every product Halsey Lidgard makes is the extent to which the base materials are tested. “We own some pretty sophisticated testing equipment,” he explains, “and we can test every kind of fabric that is available.” The company uses an Instron testing machine coupled with custom-designed software to collect data regarding the cloth sample at a rate of 2,000 data points per second. He says this same testing system played a key role in in developing the famous Cuben Fiber sailcloth for Bill Koch’s 1992 America’s Cup campaign.

According to van Dyk, what customarily happens before an order is processed is that his colleagues specify a particular material to their suppliers and then put that cloth to the test. “We get a lot of cloth in and we go ahead and test it for breaking strength and stretch. We do that with almost every lot.” Generally the company purchases its cloth from Dimension, Contender, Challenge, Bainbridge, and Cuben Fiber, he says, with all the testing done at the Mystic, CT loft that Andy Halsey founded in 1983.

Halsey Lidgard produces both crosscut and triradial-built sails, but van Dyk is quick to stress that the company’s sails are distinct for two reasons— the proprietary design program developed by Jim Lidgard, and the experience of the personnel involved. SailMaker, the software that Lidgard developed in 1984, allows the company’s designers to create sail shapes on screen in three dimensions, after which those parameters are fed to a laser cutter that creates the panels. Van Dyck says 160 other sailmakers around the world now use this program. To set up panel orientation in sail designs, the company uses Relax, a stress-analysis software program designed for the sailmaking industry.

When it comes to experience, van Dyk says that his background serves as a typical example of what Halsey Lidgard looks for in one of their staff members. He’s done 11 transatlantic crossings and has sailed around the world. “We have a great many hours of sailing,” he says of the collective time on the water logged by the staff at the company’s five lofts around the US. “We’ve all done a variety of sailing, and regardless of the sail we’re building, we use all of our practical knowledge to arrive at the best solution for design and construction. We don’t differentiate too much between the sails for an 80-footer and those for a 30-footer. We put the same resources into each sail in terms of quality, and we take extra time to put them together.”

Halsey Lidgard’s sailmakers compare the actual sails with the original computer molds by way of digital imaging. They do this by feeding high-resolution photos of the sails into the design computer and measuring them with program known as SailShooter, another technological tool derived from the America’s Cup arena.

According to van Dyk, for several years the company has produced inventories for numerous high-end clients, which always requires the optimum design, materials, and execution. These extreme custom projects regularly involve the use of Cuben Fiber, considered one of the most advanced sailmaking materials on the market, and thus Halsey Lidgard has amassed ample experience in this area. That knowledge, says van Dyk, translates to the work the company does with all its sails. “Some boats might be cruising vessels,” he explains, “but if they’re large, you address the design and fabrication issues the same way you would for racing boats. We do specialize in larger vessels, and within this range we build sails for cruising, offshore, racing, and grand-prix boats.”

Doyle Sails

Like many sailmakers, Doyle Sails offers several product lines identified by marketing trade names. Bluewater Sails, DuraSails, 2+2 mainsails, and QuickSilver Genoas comprise Doyle’s lexicon of labels for the cruising customer. But these labels are simply a point of departure, says Mark Ploch, a franchisee who owns Doyle lofts in New York and Clearwater, FL.

“We’re a custom sail loft, and every sail, just like every owner, has a unique set of needs,” explains Ploch. “If a guy owns a Catalina 30 on Lake Lanier, he’s not going to need a Bluewater style sail. We’d probably lean in the direction of a DuraSail for that customer, but we’d make some important alterations, like not building as much roach into his mainsail as we would for the same boat in Southern California. And the clews on any headsail, whether we specified a QuickSilver genoa or a sail built with Doyle Vectran, would automatically be raised for better visibility. After that, if the client didn’t have specific preferences, we’d build the sail along the lines of our normal DuraSail standards.”

Doyle Sails, which has been in existence for almost 40 years, has 20 lofts around the US. The company’s basic non-racing product is its line of DuraSails. These are crosscut Dacron products—both mainsails and headsails—without any of the costly frills included in the company’s other products. This, says Ploch, results in a good sail value for small- to medium-sized boats. DuraSails are offered with a three-year warranty.

Doyle’s next line is called Bluewater Sails. These are essentially crosscut Dacron sails with a finish and details that step them up from DuraSails. For instance, these sails are built with the reinforcement needed for ocean passages, including larger patches that are usually triple-stitched; heavier taped edges, Spectra webbing, and lower-stretch leech lines. Depending upon the usual factors—the kind of sailing a customer does, his or her sailing locale, and that person’s expectations regarding the longevity of the product—Ploch says he and his colleagues will specify a certain weight of high-tenacity Dacron. He explains that the warranty Doyle offers on its Bluewater Sails is based on details like the luff slides being sewn on with webbing, the batten patches being reinforced, all the seams being taped as well as stitched, and having large radial patches applied to reinforce the high-load areas like clews and heads. All of this, says Ploch, is standard construction protocol at Doyle lofts.

Stepping up from there, the cruising product line moves into the QuickSilver Genoas and 2+2 Mainsails. The claim that Doyle makes regarding its QuickSilver II headsails is that they offer “the low stretch of laminates with the durability of woven Dacron” at a lesser price. The 2+2 Mainsails, which can be built either of woven panels or laminated fabrics, are intended to satisfy customers who both cruise and race. The idea here, says Ploch, is to achieve product durability with two full-length battens in the top of the sail and adjustable sailshape with two longer-than-normal battens in the lower portions. Doyle also offers a proprietary product for roller-furling mainsails that it calls the “Doyle Swing Batten,” which is a rigid batten that can be articulated by way of a control line to align vertically for furling or horizontally for sailing.

What sailcloth does Doyle specify for its sails? “We actually use a lot of the latest racing fabrics in many of the cruising sails we sell,” says Ploch. “We find that cruising sailors are oftentimes the more challenging customers because they really demand more of the product than a racing sailor. So even though Dacron is probably the material we use most in bulk terms, we use a lot of composite construction materials in our cruising sails. We also build a lot of megayacht sails, in which we often use our new Ocean Weave, and in some cruising sails we’re beginning to see an application for our new D4 product.”

D4 is a laminated cloth with the base fabric assembled in the Doyle Fraser facility in Australia. It has yarns laminated in between layers of film or fabric, says Ploch. “We specify different components depending upon the order, so in this way the sailcloth is constructed around the needs of the boat.” Also among its high-end products, the company offers sails built of a fabric it calls Doyle Vectran, which incorporates Vectran in a laminate between two layers of taffeta that is then cut into a traditional tri-radial sail.

Ploch is keen to stress the importance of tailoring the product to the customer’s needs. “It works best that way. With a little information, we can put that person into the most appropriate sail. We can design the inventory to his needs. And honestly, that’s the kind of customer that we deal with a lot. Our market is very service-oriented and our buyers are sophisticated.”

Conclusions, Part One

That’s a lot of marketing lexicon and tech-talk to absorb, and there’s some hype in there, too. But there are obviously a lot of similarities: None of these major sailmakers takes customer service lightly. Anywhere above the basement level, customers can expect personal attention and methodical systems in place for determining the right materials and construction techniques.

There seems to be a consensus that woven-only sails will last longer, but will lose their top efficiency relatively early, while laminated sails will hold their designed foil shape longer, but not last as long overall. Standing outside that consensus, with a venerable company track record to back him up, is Tim Woodhouse of Hood.

The major remaining concerns, in order of importance to us, thinking in cruising terms, would be, first, long-term customer service; second, overall durability, meaning resistance to UV, flogging, mildew, poor folding and flaking, and stress at the corners; and third, general shape-holding ability. Oh…and cost.

Next month we’ll have these same sailmakers give us quotes on a set of cruising sails we’ve described to them, and look at the results of our reader survey.

———-

MORE SAIL LOFTS

While we concentrate above on some of the biggest lofts, the ones below are hands-on, customer-service oriented operations with vast amounts of experience. We just can’t cover the whole waterfront.

Ullman Sails — With 10 lofts in the US, part of 19 worldwide facilities, Ullman probably deserves to be included among the seven companies profiled in greater detail here, but the company’s bread and butter remains racing sails, principally one-design. Ullman does make Coastal Cruising Sails and Bluewater Cruising Sales;

www.ullmansails.com

Banks Sails — Another company large enough to rate coverage with the big lofts above. Banks produces three lines of cruising sails from crosscut to laminated, backed by 13 lofts in the U.S.;

www.bankssails.com

AirForce Sails — specializing in inexpensive yet durable sails online;

www.airforcesails.com

Bacon & Associates — Annapolis, MD-based broker of new and used sails;

www.baconsails.com

Bremen Sails — master sailmakers in Miami since 1962; custom canvaswork, covers, dodgers; 305/635-1717

Cruising Direct — subsidiary to North Sails with similar product line at discounted prices;

www.cruisingdirect.com

Eastern Sails — custom, crosscut sails in Massachusetts for 30 years;

www.easternsails.com

Elliott Pattison — custom cruising sails from a performance sailmaker in Newport Beach, CA;

www.epsails.com

Fairclough Sailmakers — Connecticut-based firm with 50-plus years of experience specializing in crosscut cruising sails;

www.fairclough.com

Haarstick Sailmakers — crosscut and laminated cruising sails from three lofts in the northeast;

www.harsticksailmakers.com

Hathaway Reiser and Raymond — over 100 years in business, makes triradial or crosscut sails out of Connecticut;

www.hathaways.com

Hong Kong Sailmakers — discount online sailmaker;

www.hksailmakers.com

Jasper and Bailey Sails — traditional and cruising sails, based in Newport, R.I.;

www.jasperandbailey.com

Kappa Sails — custom sails from a one-loft sailmaker;

www.kappasails.com. The PS test boat has well-cut Kappa laminate sails.

Pineapple Sails — long-time San Francisco Bay Area sailmaker;

www.pineapplesails.com

Point Sails — San Diego-based sailmaker with racing background;

www.pointsails.com

Sabre Sails — high-tech sailmaker with production based in Ft. Walton Beach, Fl and 13 agents nationwide;

www.sabresails.com

Sails East — Hong Kong-based loft with seven U.S. agents selling basic crosscut or triradial sails.

www.sailseast.com

Sobstad — crosscut cruising sails with 12 North American bases;

www.sobstad.com

The Sail Warehouse — discount sails new and used;

www.thesailwarehouse.com

Shore Sails — durable cruising sails from a performance sailmaker, three lofts in New England;

www.shoresails.com

Schurr Sails — crosscut and laminated sails, based in Pensacola, FL with agents in nine other U.S. locations;

www.schurrsails.com

Sperry Sails — traditional expertise with technological advances in Buzzards Bay, MA;

www.sperrysails.com

Yager Sails — custom offshore and cruising sails out of Veradale, WA;

www.yagersails.com

How do you leave out Elvstrom EPEX?