Like the French Impressionists of the 19th century who changed the way the world looked at art, beginning in the 1970s a handful of boat designers and builders located in Santa Cruz, California, had a similar effect on the sailing world. Led by Bill Lee, the “wizard” of the bunch, designers and builders like George Olson (Olson 30), Terry Alsberg (Express 27), Ron Moore (Moore 25), and others introduced a ‘fast is fun’ concept that continues to influence today’s design and production methods. Initially focused on the development of production 27-footers, Lee’s influence eventually extended beyond, to 70-foot turbo sleds (and their harbinger, the record-shattering Merlin, whence the nickname “wizard) and back again to the Santa Cruz 52, a legitimate performance cruiser, (emphasis on performance) which PS reviewed in the July 1, 1995 issue. Interestingly, his efforts preceded a similar revolution on the East Coast, when the Johnstones introduced the J/24 and, subsequently, a line of four-person ‘sprit boats’ that has grown to include offshore cruisers.

History

At about the same time the Beach Boys were making waves with surfing music and Hobie Alter was changing his focus from surfboards to catamarans, Bill Lee surfaced on the waterfront in Santa Cruz, on the northern end of Monterey Bay. Lee was born in Idaho, raised in Newport Beach, where he began sailing, and graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering from Cal Poly, Santa Barbara. His penchant for sailing was fueled by the sport’s multi-dimensional aspects.

“No other sport combines meteorology and atmospherics, fluid dynamics, and a chess game,” he says.

While working as an engineer for Sylvania, he sailed in the high winds and waves of the Pacific that had their origins in Alaska. “On a typical day, we’d beat 13 miles north to Davenport, round a mark, reach for 30 miles to Pt. Lobos, and beat back to Santa Cruz.”

Lee was already experimenting with boat design and construction, having completed his first boatbuilding project, a 42-foot plywood boat he says was “too light.” In 1969 he followed with Magic, a 30-foot balsa- cored speedster weighing only 2,500 pounds that he describes as “radical— a 30-foot surfboard.”

He crewed aboard a Cal 40 in the 1971 TransPac with an owner who decided he wanted a faster boat for the 1973 race. With the commission to handle that project, Lee ended his corporate career and donned what was to become the wizard’s cap. His first two designs were Panache, a 40- footer, and Chutzpah, a 35-footer that took corrected-time honors in the TransPac in 1973 and 1975.

The “factory” for Bill Lee Custom Racing Yachts was a 200-foot long, low-ceiling chicken coop (that’s no exaggeration, we’ve been there) located on a hillside in Soquel in which he also stored a 1931 Rolls Royce he intended to restore. Corporate headquarters was a camper trailer located next to a milking shed that housed a welding shop in which lightweight yacht parts were forged. The building has since become a local landmark.

In the ensuing 20 years, many of the most famous American race boats made the journey via truck from the coop to a launch site.

Design

That the Santa Cruz 27 became Lee’s first production boat was an accident. The boat began life in the imagination of a sailor who wanted a sailboat that met the IOR Quarter-Ton measurement rule of the time.

“That dictated a boat that was 25 feet long, 9 feet on the beam, and meant that the hull had bumps in all the right places,” Lee says. “But that boat never got beyond the paper stage when the owner decided he wanted to be first to the bar.”

As a consequence, Lee says, “The SC27 and its successors, except for the Santa Cruz 70, were not designed to a racing rule. We studied the racing rules to see what they said. At the time, the Cal 29 and Cal 34 we considered state of the art. However, racing rules have ‘go-slow’ factors in them that improve handicaps but reduce speed. I eliminated the go-slow factors.”

In the process, Lee urged the performance sailing world forward by designing boats that were faster by virtue of design and light displacement, without compromising structural integrity. In most cases, that produced long water lines, good form stability, and smaller, more spartan interiors.

In the case of the SC27, the final product “had the same rig, keel, and rudder [as the quarter-tonner], but was lengthened to 27 feet and narrowed at the beam to 8 feet. It has the same surface area and, generally, required the same raw materials.”

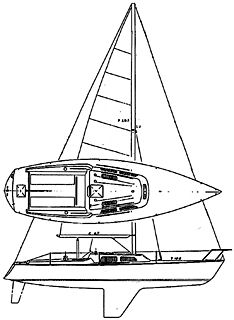

It also has a long “J” dimension of 10.9 feet, which allows large spinnakers to be carried, and short boom offset by a high-aspect mainsail. An external influence was the Santa Cruz – Santa Barbara race, a 225-mile ocean sleigh ride past Point Sur and Point Conception, points of land that produce gale-force winds. Accordingly, Lee designed a self-bailing cockpit and a relatively small companionway opening.

Hull #1 was finished in 1974 for the client, and “was built for profit,” Lee says. However, George Olson, an employee of Lee’s at the time, along with Lee and a few others at the coop, were so taken with the boat that they built the next five for themselves.

“Hull #7 was the second boat we built for a profit,” says Lee. “It was for the owner of a Cal 40 who, while doing the Newport-Ensenada race, was passed by our boat going downwind. He sent us a $500 deposit check along with a request for a price list.”

During the production run, the ballast was increased twice, from 900 pounds to 1,400 pounds, “because it was too tender,” and, with hull #22, to 1,600 pounds, “to improve performance to weather in the ocean.”

Concurrent with SC27s rolling out the door of the coop, Lee was busily designing and constructing Merlin, the now-legendary 68-footer displacing only 23,000 pounds. Launched in 1976, Merlin broke the TransPac record, as well as that of virtually every ocean race she entered, proof that lightweight boats are fast and can be durable. She still makes a cameo appearance in West Coast offshore races.

By the time production of the SC27 was discontinued in 1977, more than 150 had rolled off the line and Lee was constructing the Santa Cruz 50, also a race-winner that precursed a series of 70-footers. The 70s proved so popular, and fast, that class rules were adopted for ocean races.

Lee sold the company in 1995; it is now operated as Santa Cruz Yachts. Now 61, he spends days brokering sailboats and as a consultant to the Maxi 86 fleet.

Appearance

Simple and straightforward describes the appearance of the SC27, though when viewed from abeam she has an almost menacing look. Her low freeboard, long foredeck, and a rectangular port constructed of black Lexan on the front of the cabin, a Lee signature, clearly move her out of the Martha Stewart category. Her appearance hints at her performance potential.

The long foredeck is balanced by an equally long, wide-open cockpit, so the low-profile house, also outfitted with black ports, occupies only a small space center stage. The mast is near the intersection of the cabin and deck.

She has considerably less freeboard and is sleeker than many of her 1970s contemporaries. Naturally, the low profile comes at the expense of headroom belowdecks.

Rig and Deck

Though conceived to make boathandling easy for a race crew, the SC27’s deck layout also makes daysailing a simple chore, even for singlehanders. And, her rig is stout enough that running backstays are unnecessary, though it can be tweaked with a split backstay to improve sailshape. The single-spreader masthead rig was equipped with a babystay to prevent excessive mast bend.

The same 51″ long seats that provide room for helmsman and crew to operate jibs and spinnakers from the cockpit also provide the casual sailor with room to stretch out. Seats are 18″ wide and coamings 10″ high, so add cushions and she’ll be comfortable. The 18″ of space between the traveler and companionway adds another seat. A downside is that the fuel tank is stored in the stern, but occupies space in the cockpit when motoring.

The standard arrangement of winches placed two Barient 21s in the cockpit, and Barient 10s on the cabintop. A 36″ long section of sailtrack at the cockpit coaming puts genoa sheets at the fingertips. There are 48″ tracks on deck for smaller overlapping headsails, and short tracks on the cabintop to allow close sheeting of a jib. The toerail is an aluminum section with holes that allow different placement of blocks. However, freeboard is only 24″, so crewmembers can expect to be wet going to weather in high winds or waves.

A bowman, or sunbather, will find comfort in the 8-1/2′ of space forward on deck

On balance, form meets function on the deck, and the cockpit is large enough to be comfortable.

Belowdecks

It would be too kind to call the space below rustic because that intimates a level of style. In fact, the space belowdecks is strictly functional. Headroom is approximately 48″—sitting headroom only, in other words— and ventilation is provided only by a vent located at the companionway. The area provides bunks for four and space adequate for cooking camp-style. A cooler large enough for chilled beverages is tucked under a wooden step at the foot of the companionway. A portable head is located forward of a half-height bulkhead. A 23″ long wooden cabinet serves as a nav station. It also conceals an electrical panel that is close at hand but out of the elements.

Two church-style bench seats offer a place to sit while eating. Constructed with 16″ high backs and enclosed ends, they will place crew in a secure spot in a blow.

Storage is outboard of the seats in open spaces measuring 16″ deep and 20″ long. Lee avoided the weight associated with cabinetry while still providing functional storage areas. In fact this has always been a pretty effective stowage arrangement, allowing easy access to personal gear and good ventilation.

The berth in the forepeak is 6’6″ long, and wide enough for two adults; otherwise, racers remove the cushions and use the area for sail storage. Berths port and starboard in the aft quarters are 7′ long and 24″ wide, so provide snug spots for skinnier members of the off-watch. The space below the cockpit is wide open, and can store outboard, fuel tank, and boat gear.

The mast support on our test boat was an upside-down, U-shaped section of aluminum stock spanning the cabintop, attached to two vertical oak supports that bear a striking resemblance to tillers on a daysailer. Supports are fiberglassed into a knee in the hull structure.

“From Hull #28 on, we changed the mast support,” Lee says. “It was initially a beam bonded in the deck that we replaced with the framework of 1/4″ aluminum spanning the deck, supported by two, 2″-square oak posts.” The design disperses loads better than a conventional compression post. Holes in the aluminum support provide a handy place to store coiled sheets and guys.

Regardless of the boat’s spartan accommodations, berths are long enough, and cooking aboard is possible. The lack of a hull liner means she’ll be cool belowdecks during early spring and late fall. However, crews aboard the SC27 have made many California-Hawaii trips. In fact SC27 sailor Norton Smith held the singlehanded TransPac record for 10 years.

Construction

Since she was built three decades ago, her fiberglass layup was very straightforward compared to today, and typical of the generation. Though Lee does not recall the exact lamination schedule, he says, “Hulls were constructed of roving, 3/4-ounce mat, and a balsa core to within 10” of the hull-deck joint. The deck was a combination of roving, 10-ounce cloth, and balsa.

“From a mechanical standpoint, the SC27 is pretty conservative and, if anything, it’s overbuilt. It was designed for J. Q. Public, which meant that it had to be more crash-resistant than a race boat, and have longevity.”

The owner of our test boat said, “Some owners feel that you’re going to step through the cockpit sole because it was constructed of a thin laminate.” Many have added additional layers of stiffening material, as Mark Soverel did to the bow of the Soverel 33.

A chronic problem is that the sail tracks tend to leak, a function of the hull flexing and old-fashioned bonding agents. However, most owners say that ports do not leak. A critical element when considering purchase of a used boat is a careful inspection of the deck for spongy spots that suggest the intrusion of water into the balsa.

Performance

We tasted a large enough sampling of SC27 performance potential during a two-hour sail on Puget Sound, concluding that she’ll be fast on any point of sail, and does not require America’s Cup talent to reach peak speeds.

We began the day sailing in 2-3 knots of wind which, for most boats, would require motorized propulsion. Not the SC27; the GPS recorded over two knots of speed flying a full mainsail and genoa, working to weather close to the wind.

After rounding a mark and setting the spinnaker in what appeared to be zero apparent wind, boatspeed registered 5 knots, so we were sailing about as fast as the breeze. Rounding a second mark and heading upwind in breeze building to 7- 8 knots, we sailed at over 5 knots hard to weather. Easing sheets, we sailed on a tight reach with a mainsail and 145-percent genoa. Our handheld anemometer displayed 8-10 knots of apparent wind and the GPS recorded 7.5 knots of speed over the ground (in negligible current).

When windspeed exceeds about eight knots on a beat, the racing sailor will maximize performance by placing weight on the rail and minimizing the time the foredeck crew spends forward of the mast.

Though we did not sail in wind or wave conditions that allowed the hull to break loose on a run, surfing down ocean waves at speeds in the teens in a common experience.

The boat’s 4-foot draft creates a challenge when launching at a ramp. Many owners add tongue extensions to their trailers that ease the chore. Others, including the owner of our test boat, choose another alternative: He parks his trailer at the top of a ramp, attaches a lengthy cable to the bow and bumper of his support vehicle, and allows the trailer to back downhill using the front wheel on the trailer for steering.

Boats are powered at 5-6 knots with a 4-hp. outboard. The owner of our test boat relied on an aging Seagull until it was deep-sixed and replaced by a more current model.

A common criticism is that the motor mount is underbuilt. It is attached to the stern with a quick release mount that allows it to be deployed or stored easily. However, the mounts are wobbly. We’d beef them up before heading into any serious wave conditions.

Conclusion

Bill Lee’s “Fast Is Fun” slogan has been adopted by a whole generation of sailors who may not even know where the saying comes from. Applying the logic of the ages to the idea, if fast=fun and light=fast, then light=fun. Unfortunately, this concept has usually fetched up against another, equally cherished concept in sailing: If fun=safe, and safe=heavy, then heavy=fun. So Lee’s reputation for building fast boats comes at a price: Some people assume that his type of boats are unsafe. This is unfortunate and undeserved. The SC27 and all its larger siblings, like the SC50s and SC70s, have been successfully campaigned in rugged ocean racing conditions for many years. SC27s constructed nearly 20 years ago are still racing outside the Golden Gate in blustery northwesterlies.

Critics may ignore the fact that these boats were not constructed with weight-adding furniture that increases displacement and impedes speed. Cockpits and deck layouts on the SC27 are as comfortable and functional as will be found on any “conventional” 27-footer. Spaces belowdecks will be adequate for daysailors, but a compromise for cruisers—though berths and stowage for personal gear are actually decent. As with the Hobie 33 and Soverel 33, the primary inconvenience will be the lack of headroom and use of a portable head.

In response to a question about “Liveability” aboard SC27s in a PS Boat Owner survey some years ago, one owner said, “You can’t have everything. This is what friends with cruisers are for—we get there first and reserve space for them.” On the question about “Speed,” the same reader said, “Let it blow. Let’s go surfin’.” And on “Seaworthiness” he said, “Boat can take it. Crew can’t.”

A small-boat owner who wants to step up to a bigger boat, or a sailor interested in sailing in light breezes or increasing speed in a fresh breezes will be smart to check out the SC27. Used boats with motors sell in a wide range, depending on their condition and equipment list. In a scan of the Internet and the Santa Cruz class association website, we saw asking prices from $6,500 to $19,500, although the latter was an aberration. The normal asking price range is between $9,000 and $13,000.

The national class association website is active and well-maintained. The address is www.sc27.org.

*Ballast differed during the production run. Hull #1 had a 900-lb. keel; Hulls 2-23 a 1,400-lb. keel; Hulls #24- 145 a 1,600-lb. keel.