Veteran readers know how this works. For newer readers, suffice to say that near the end of each year Practical Sailor’s staff examines that year’s issues and picks the gear that impressed us the most. Our restrictions are minimal. These items can be something entirely new, an improvement to an old approach, big, small, novel, unique—anything that demonstrates usefulness and value to a boat owner.

Our lists are combined, mulled, culled, discussed (sometimes with spirit) and, finally, for no particular reason, reduced in number to a manageable group, in this case, 10. So here, in no particular order, are the products that make up Practical Sailor’s 2004 Gear of the Year.

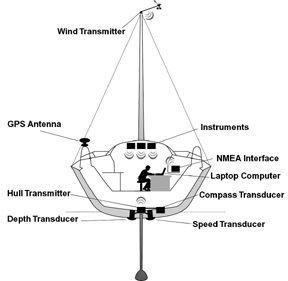

Tacktick’s Micronet System

Wireless technology is here now. Maybe it’s a new sign of the Zodiac. It may even require a new language: pods, WiFi, chips, PDAs, “soft targets,” networking (including one system called “Bluetooth,” another called “EYE”), etc. The wireless mania has been sneaking into our lives for quite a while now, spearheaded by sly gadgets like TV controllers, garage door openers, and the like. For marine applications, it’s likely to become a torrent; the advantage being that wireless technology can greatly reduce the amount of complex wiring, cables and connectors that add heavily to boat costs and are prone to corrosion.

In the Nov. 1, 2004 issue, PS took a wide-eyed look at the new-wave technology, ranging from wireless autopilot remotes to free-standing anchor sensors. Already involved are famous names like Brookes & Gatehouse, Simrad (which owns B&G), Garmin, Ockam, Hewlett Packard and the French firm called NKE.

Singled out in the report for a bit of extra attention was Tacktick’s Micronet system. Without wires, it brings to a nav display information about wind, depth, speed, and heading, and can interface and communicate with an autopilot, laptop, chartplotters and GPS units.

The British company, which back in 1996 pioneered a digital compass for small racing boats, offers several product lines, for racing dinghies, sportboats, and larger cruising and racing boats. All are sealed and airtight, with individual solar cells that make them largely self-powered—with only an occasional need, after heavy usage, to “park” them in the sun for a catch-up charge. These systems are not entirely wireless, however, because the speed and depth transducers are linked to a central unit via conventional cable, but we definitely like the versatility of a wireless anemometer and wireless displays.

PYI Floor Anchor

The very smallest of the year’s favorites was a much-needed item developed to meet an ISAF (International Sailing Federation) requirement that racing boats must have floorboards firmly secured.

The maker, PYI, Inc., calls it a floor anchor, but it’s really a beefed-up bayonet twist-lock panel fastener designed to hold down the loose floorboards found in virtually all boats. This is why we think the broad application of this device qualifies it for inclusion in our compilation of Gear of the Year.

The flush-mount floor anchors, properly installed, will keep you from getting maimed by a flying floorboard if your world goes topsy-turvy or, heaven forbid, you take on a lot of water.

These floor anchors are easy to install, but you’ll want the installation kit, which has a custom bit that drills precision holes with several diameters that accommodate the pin’s shoulders and the countersink.

Once in place, the anchors are released easily with a coin, table knife or screw driver. Reportedly, they’ll last forever—if you don’t let them get gunked up with dirt, debris, and the syrup in which you soak your pancakes.

Because they’re machined of 316L stainless to close tolerances that assure excellent fits, the anchors are not cheap. The installation kit costs $25 and the anchors are $17 or $18 in two sizes that fit 1/2″ to 3/4″ or 1″ to 1-1/4″ floorboards. (The installation kit was $45 when we first featured these devices in the Jan. 1, 2004 issue, but a PYI spokesman said they’ve since lowered the price to break even in order to sell the anchors.)

Pricey? Yes. But they can give you peace of mind when it’s sorely needed. If you do heavy-duty sailing, PS strongly recommends them. It would be nice, too, if the builders of quality boats intended for ocean work routinely installed these devices.

Rayovac’s I-C3 Battery

Always needed, in not inconsiderable quantities and multiple sizes, aboard most any boat are dry cell batteries. Sold commercially for more than 100 years, they are close to man’s oldest source of portable power.

Gulping down the power from these little devils on board your boat are flashlights, portable GPS units, digital cameras, chronometers, the binocular compass light, the CD player, fans, cell phones, VHF radios, and so on. Try doing without this stuff and you’ll see how long you remain the captain of the ship and the master of your fate.

If your experience matches ours, the 1.5V batteries you need too often are the size you don’t have. However, many of them are AAs. That’s the size PS elected to test. (To work with all sizes would have made the report far too complicated.)

One good dodge is to carry, among all the other stuff, rechargeable batteries and a charger. With this in mind, PS set about to test disposable and rechargeable AA batteries and a few chargers.

Our big seven-page report, which appeared in the July 15, 2004 issue, evaluated batteries from four major brands—Duracell, Eveready (Energizer), Radio Shack, and Rayovac—and again, to keep things manageable, did not include those from smaller manufacturers.

Included were alkalines, rechargeable alkalines, Ni-Cads, Ni-MHs and Lithiums. They were tested in various devices (a flashlight, a portable GPS, and a handheld VHF) and on a test rig using a string of resistors, a resistor/divider network and an analog-to-digital converter, all feeding data once a second to a PC.

The testing was aimed primarily at determining which batteries provide the greatest value. However, the report also included valuable data and conclusions about which battery types are best for various uses (shelf-life often is the determining factor).

Anyone looking for a single answer would find it in PS’s conclusion that, for most purposes, the Best Buy is the Rayovac I-C3, but that you should keep a few alkalines, for emergencies.

Surface Dive Deck Snorkel

Moving now from batteries, which everybody uses, to something that only some readers may use, direct your attention to an unusual piece of gear that was featured in the Chandlery column of our Aug. 15, 2004 issue. It’s called a Deck Snorkel, an Australian-made device for underwater maintenance and for recreational sightseeing. It’s very simple. It’s also safe, although you need to be competent and cautious in the water or have certified dive training.

]PS found this device so utilitarian while testing anchors in Florida waters that we bought it. It’ll be very handy to scrub the bottom of our test boats, clean fouled props, inspect mooring chain, locate anchors and retrieve winch handles, tools, glasses. Being fine but typical boatmen, PS staffers commit all of these gaffes. The Deck Snorkel uses a 12V compressor in a tackle box to pump air through a 20′ hose to a floating accumulator tank out of which runs a 28′ hose to a standard scuba regulator mounted on a web chest harness. The hoses all are quick-connect types. The whole rig, which weighs 29 pounds, stows in a duffel bag. Empty the duffel, plug the 16′ power cable into the house battery, wait for the accumulator tank to charge at 18 psi (much lower than a scuba rig or engine-driven compressor), don the harness and adjust the mask. That’s it.

The Deck Snorkel draws about 11 amps, so with a single 12V deep-cycle battery (Group 24, 90 amp hours) you have underwater time of almost six hours, without running the engine. If you’re working and breathing hard, make that four hours.

The one-diver model we bought (there are several bigger models) is not cheap ($969). But it’s a workhorse tool and fun to use; just always know exactly what you’re doing,

Si-Tex ColorMax 6

From time to time, PS runs head-to-head tests of a limited number of products. Sometimes it’s because of the unhandiness of testing and reporting on a workshop full of complicated equipment. Other times, it’s because it’s advantageous to spend more time with less gear. Not infrequently, it’s because new or improved models pop up—especially in the electronics field.

For instance, in the Aug. 15, 2004 issue is a detailed report on two small color plotters—the Si-Tex ColorMax 6 and the Navman Tracker 5600. (The latter’s viewing screen was greatly improved after a PS test two years ago of 10 plotters revealed that the Navman screen had poor sunlight performance.)

PS did not test these two machines for their GPS performance, speed of signal acquisition or positional accuracy. That’s because there’s no significant difference between various makes. The test was focused on screen viewability in direct sunlight and on the user interface—both software logic and the ergonomics of control.

The two plotters were mounted side-by-side, with their antennas outdoors, and connected to an identical power source. After that, PS simply worked through settings and functions, using the latest C-Map NT chart chip for the geographic work.

The procedures then were repeated after the plotters were taken outdoors and positioned to face bright sunshine. To make sure, the plotters were taken inside and, over several days, checked again and at night with the lights out.

This was a “loaded” test, because the Si-Tex ColorMax 6 is billed as “sunlight viewable” and the Navman Tracker isn’t. Navman deserves credit for the screen development (the test showed that the Navman’s screen has been improved). And its controls are among the least complicated and most practical PS has seen. However, if you intend to mount or use a plotter in direct sunlight, the less-expensive Si-Tex ColorMax 6, is the hands-down choice.

Zodiac FR 310 ACTI-V Cadet

Early last spring, as we don’t do nearly often enough, a goodly portion of the PS staff adjourned to Sarasota Bay in Florida. The objective: Test and report on seven roll-up boats, which are identified as having inflatable decks and keels. It requires considerable manpower to unpack, absorb directions, rig and launch seven different boats from Mercury, Achilles, Avon (Zodiac), Bombard (Zodiac) and West Marine.

Then comes the real work.

Rowing an inflatable is hard work if there’s any wind around. It leads to naught but the opinion that inflatables cry for outboards.

Next came timed runs with two outboards—a 5-hp two-stroke and an 8-hp four-stroke, with both one and two passengers aboard. Each boat-engine-passenger combination was run over a measured course and checked for planing; top speed; high-speed turning; form stiffness; cavitation, and driver and passenger comfort.

Multiply all these combinations (and add in the time to make chart entries and detailed notes) and it should be clear why such testing takes many long, hard days.

Specifically, these boats fit in the middle of the range of available blow-up tenders. At one end are the old-fashioned flat-bottom dinghies with wood or aluminum floors. At the high end are RIBs (rigid inflatable boats), which have fiberglass or aluminum bottoms and inflatable rims. RIBs are fast, stiff, expensive, heavy and not easily stowed.

There are several types in between, and the ones in this test have no real generic name. Except for a hard transom, they are entirely inflatable, including the deck, to give stiffness, and a keel of some sort to provide directional stability. Together, the deck and keel provide a hull-like shape. Their great advantages are that they’re light, stowable, and affordable.

The specific models tested were the Mercury 310 Airdeck Hypalon, the Mercury 310 Airdeck PVC, the Achilles LSI-104, the Avon R310 Rover, the Bombard 305 Typhoon, the Zodiac FR310 ACTI-V Cadet, and the West Marine RU-310 HP.

When the sun set in the golden west on the last day, the squad of tired testers were exhaustively familiar with these boats. They were unanimous in their view that, despite having a name almost as long as the boat, the Zodiac FR310 ACTI-V Cadet was the top boat. It wasn’t the fastest, but the testers liked its stability, tracking, handling, and general feeling of seaworthiness. The Mercury 310 Airdeck Hypalon (which knocked down Best Buy honors) was second, and the Avon 310 Rover was third.

Trinidad SR

PS has been testing anti-fouling bottom paint for so long that we harbor a slight fear that Nature, for revenge, will turn us into a cirripedia (barnacle), sea grape, or crepidula fornicado (a.k.a. quarterdeck).

Each year, in Connecticut and Florida, the process includes obtaining, preparing and painting boat bottoms or panels, and then finding just the spots to plant them.

After many years of effort, PS has learned that, wherever the tests are done, there are good and bad years in fouling. Sometimes, the fouling runs rampant; other times there’s little bottom growth. There can be pronounced differences in areas only a few miles apart.

These variations complicate the testing. But, as long as they are recognized, the testing seems to prove valuable to readers. (During PS’s Reader Call-In periods—Tuesday and Thursday, 11:30 a.m. to 1 p.m. ET—inquiries about bottom paint predominate.)

Basically, PS identifies the paints, submits the panels to the brine, observes the paints’ behavior over extended periods of time, and publishes the results.

In the latest round of annual testing, 54 paints were used. That’s a lot of panels. In New England, the panels were pulled after three months because of a hurricane threat. The Florida panels were suspended on racks in a Sarasota tidal basin.

The results were published in the March, 2004 issue. (Our Florida panels were planted in water so sheltered that it turned out to be hypoxic, and yielded no useful comparisons.) Interlux’s Micron 66 was the best, as well it should be. It costs $212 a gallon—and is not for use in fresh water.

The usual close examination of the results lead to an additional observation. One paint, with a mid-range price of $150, was almost as good. The paint is Pettit’s Trinidad SR. What’s more, it has been a consistent performer over several years. It is that longevity of excellence that makes Pettit’s Trinidad SR worthy of Gear of the Year recognition.

Fluke 111

As pointed out in the report in our April 15 issue, the first step when something electrical goes awry should be to grab the multimeter. There are many kinds and many varieties. A basic instrument usually includes an ammeter, voltmeters and ohm-meter, all selectable. The fancy jobs can measure parameters of capacitance, inductance, temperature and even test sockets for checking diodes and transistors.

The first really portable multimeters turned up in time for World War II. They were called VOMs, required batteries, and were rather cumbersome. Many variations followed, including Hewlett Packard’s VTVM (Vacuum Tube Voltmeter).

Limited in accuracy by their analog D’Arsonval meters, these early instruments were useful. But they were clunkers compared with what happened when LCDs and digital meters took root.

For a concise test of the multimeters boat owners seem to need (boatyard professionals were polled, too), PS gathered up seven multimeters. They were a Radio Shack RS22813, Gardner Bender’s GOT185A and GOT 2000A, Ancor’s 702073 and 702078, a Tripplett 9025 and a Fluke 111. Be careful of El Cheapos; multimeters are supposed to precision instruments.

They were cranked repeatedly through tests of overload protectors; battery indicators; continuity checks; data and max/min hold functions; auto ranging; test leads, and just how comfortable and easy each was to use.

The bottom line: The $30 Radio Shack held its own at the entry level, but the Fluke 111 got high praise and PS’s recommendation. Check the price here and there. Although the price seen most often is $110 to $140, PS bought one on e-Bay for $75.

Furuno 1712

Unlike the small test described above of two color plotters, most PS testing is done with as many as possible products in a category. Even so, the category usually has to be, in some fashion, parameterized. (We just invented another word, but we’re not sure we like it much.) When it comes to electronic equipment, the limitations are mandatory. The competition in such gear is so intense that new models frequently appear on the market before we can complete the testing and report on the prior ones.

This year, when radar sets appeared on the work list, we decided to stick to those that a majority of boat owners could afford and install in a weekend. You might view the sets chosen as entry-level, stand-alone systems.

Chosen for testing were the Furuno 1623 and 1712; the JRC 1000MKII, 1500MKII and 1800CP; Raymarine’s Sl72Plus, and the Simrad RA 30. Five are monochrome, two are color. (The Furuno 1715 is identified in the PS report as the Furuno 1712. Shortly after our test, Furuno replaced that model with the 1715, identical except for the size of the case and a larger radome.)

Besides developing an excellent feel for installing and setting up (tuning controls, bearing alignment and display timing adjustments), our testers subjected these sets to rigorous examinations of menu navigation; target resolution; screen brightness and contrast, clutter management, and various special features like watchman mode. And power consumption, which has been reduced significantly in recent years, was carefully measured.

The test site was perfect—a stone wall at 15′ above sea level on Long Island Sound’s Avery Point near the University of Connecticut. At ideal distances were two fixed radar targets (a lighthouse and a batch of low rocks) and lots of traffic (from big ferries to small pleasure craft).

In the end, it was the Furuno 1712 (now the 1715) that averaged out as the best overall black and white set, and earned the top spot. The six-page report in the September issue was, we thought, a primer with a wealth of information critical for consideration by those who might be about to acquire their first radar set (and might be tempted to buy a set solely because it has a superior range).

The Bungy

The last Gear of the Year item is a favorite. The choice of the Bungy was very easy, because it’s new, not terribly expensive, and very practical. (Of course, anything “practical” we tend to like.) The Bungy made its debut in the Chandlery column of our July 15 issue.

This product is simply a one-piece molded rubber glob that can be used singly or in multiple numbers to provide stretch in any line up to 3/4 inches.

It very effectively eases the shock load on any line. Better yet, unlike all other snubbers, it can be attached to any line without freeing the line or having to tie knots or make loops.

In our in-house test of the Bungy, the device gave 2-1/4 inches of stretch with a line tensioned to 200 pounds. Three or four bungies on the same line would give up to about 12 inches of elongation, if tensioned to about 550 pounds. That’s a good load for an anchor rode in very stiff winds.

The Bungy could also be used with a preventer, soft boom vang, or mooring line, and would certainly tame the jerking that often occurs when towing a dinghy.

Per Stalquist, of Scandvik, saw the Bungy in Sweden and grabbed a bunch to sell in the U.S. In our opinion, they’re pricey (at $29.90 for a pair) but so intelligent that they’re irresistible.

Contacts

• PYI, 800/523-7558, www.pyiinc.com

• Tacktick (Layline), 800/542-5463, www.layline.com

• Rayovac, 800/237-7000, www.rayovac.com

• Surface Dive, 800/513-3950, www.surfacedive.com

• Si-Tex, 727/576-5734. www.si-tex.com

• Zodiac/Bombard/Avon, 410/643-4141, www.zodiac.com

• Pettit, 800/221-4466, www.kop-coat.com

• Fluke, 800/443-5853, www.fluke.com

• Furuno, 360/834-9300, www.furuno.com

• Bungy, Scandvik, Inc., 800/535-6009, www.scandvik.com