Photos courtesy of e Sailing Yachts

The trophy daysailer market is rife with branding, image, and various forms of snob appeal. The e33, however, makes its pitch on practical grounds. Reports from the field highlight the performance/comfort/control combination that makes the e33 a fun raceboat. You don’t need a big crew, you can exercise your tactical talents to the max, and you give away nothing in boatspeed. Our time sailing the e33 convinced us that it is not only a legitimate performance sailboat, but that attaining that performance is sinfully easy. The e33 daysailers bonus points include a cockpit that takes up more than half the deck space and can hold five or six adults comfortably; cockpit-led control lines; carbon-fiber spars; and a hydraulic headstay control. Below, Spartan accommodations include berths for four, an enclosed head, and a built-in cooler. With the look of a classic and the innovative design of a modern daysailer, the e33 is e Sailing Yachts intelligent, inspired, comprehensive attempt to capture the fun of performance sailing.

****

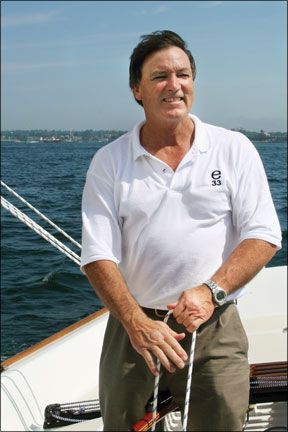

With 50 lofts in 30 countries, you might think that Robbie Doyle, founder and president of Doyle Sailmakers, would have more than enough to keep him busy. Nonetheless, hes leapt into boatbuilding. Partnered with designer Jeremy Wurmfeld, Doyle created the e33. One of the many attractive, expensive daysailers to hit the market recently, this 33-footer has minimal accommodations, a 16-foot cockpit, and a host of solutions and innovations.

Doyle remembers how the e33 came about: “Dirk Kneulman (Etchells builder and former world champion), Jeremy, and I were fantasizing about a boat that would be as much fun to sail as the Etchells without the bumps and bruises, a performance boat that could be sailed to the max with no hiking, a boat that gives you no excuse not to sail.” A college All-American (Harvard 1971), Doyle apprenticed with Ted Hood early in his career, spent significant time pursuing The Americas Cup, then founded Doyle Sailmakers in 1982. “Much of my course work was in naval architecture at MIT,” he explained. That background, he asserts, not only taught him the basics of boat design, but influenced his approach to sails. Utilizing the principles of elliptical loading demonstrated in the famous Australian wing keel in 1983, Doyle became the first to apply the principle of Elliptical Aerodynamic Loading to sail shapes. The e33 thus grew out of Doyles racing experience, his feel for what sailors want, his understanding of technology, and his capacity for innovation (Stack Pack, Quicksilver reefing, etc.).

Wurmfeld was trained in conventional architecture. After a short time on the job, however, he bolted his desk to become a charter skipper in the Caribbean. After that, he came ashore to enroll in naval architecture at Westlawn Institute of Marine Technology. That degree led to a six-year stint at Sparkman & Stephens before he went out on his own in 2004. Wurmfeld also has raced Etchells on Long Island Sound for years.

Kneulman (Ontario Yachts), who builds Sonars as well as Etchells, decided not to build e33s, despite his involvement in the boats development. That led Doyle and company to Waterlines Systems of Portsmouth, R.I. Small but diversified, Waterlines has specialized in “one-design optimization” and also builds J-22s, J-24s, Farr 40s, and Mumm 30s under license. To date, the company has built more than 20 of the new boats.

The Design

The Etchells, a 30-foot, three-man keel racer introduced as a candidate for the Olympics in the mid 1960s, made a stellar starting point for the new design. Originally known as the e22 (for its waterline), the Etchells failed to be chosen for the Games despite dominating the selection trials. There are now more than 50 fleets around the world with more than 1,300 boats actively racing. Rock stars such as Dennis Conner, Jud Smith, and Dave Curtis as well as Kneulman and Doyle attest to the quality of Etchells competition. Called “eternally contemporary” and praised for tacking in 70-degrees and slipping effortlessly through the water, the boat has spawned more than its share of fanatics.

With a ballast/displacement ratio of 63 percent, Etchells are very stiff, Wurmfeld says. The e33s ballast/displacement number is 43 percent, so it, too, stands up well in a breeze. The boats narrow beam (8 feet, 6 inches) minimizes the effect of weight on the rail; the “no hiking” part of its personality is for real.

“We gave the e33 a proper bulb at the end of a 5-foot, 9-inch keel where its weight pays off,” Wurmfeld says.

Like many of the others vying for the “perfect daysailer” mantle, Doyles boat is better for being bigger. Top speed (projected at better than 10 knots) is unlocked by a generous, 27-foot waterline length. Large overhangs forward and aft help assure that its dry underway.

The biggest benefit of its bigness, though, is its huge cockpit. Deep enough to be supremely secure, it seems to go on forever. From transom to companionway, it offers uncompromised lounging, sailing, and elbow room.

The slender hull has V-sections forward of the keel for weatherliness and wave handling. Relatively slack bilges and an easy run of U-shaped sections aft strike a balance between minimizing parasitic drag and providing lift at high speed. Wurmfeld says the foils also reflect the tension between racing efficiency (deep/high-lift) and daysailing practicality (moderate draft/tracking).

One-design competition is always a possibility, but Performance Handicap Racing Fleet (PHRF) is the boats most-likely arena. It rates 90 with a cruising chute in New England and 103 without.

Reports from the field highlight the performance/comfort/control combination that makes the e33 fun to race. You don’t need a big crew, you can exercise your tactical talents to the max, and you give away nothing in boatspeed.

“Starting a new company, we had to beware being all things to all people,” Wurmfeld says. “But the look of the boat was critical. The relationships of masses, shapes, and angles needs to be pleasing to the eye. The counter and transom were my treatment, and Robbie had the last word on the bow angle.”

Like an Etchells, the e33 can be dry-sailed and trailered. At 5,800 pounds, its targeted for the 3-ton lifts at many yacht clubs. “You need a 300-horsepower tow vehicle,” Doyle says. “Strong points for a lifting bridle are built into the boat.”

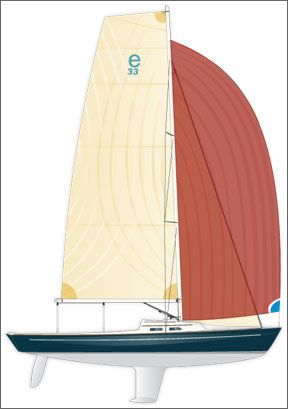

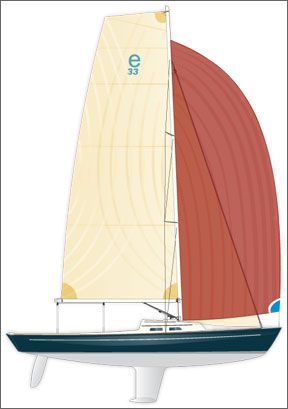

The Rig

We asked Doyle if there was a connection between the elliptical aerodynamic loading that he pioneered in the 1980s and the high-roach sailplan of the e33. “When I was building sails for Courageous back in 1977, we tried a high-roach main as an experiment. It became the only main we used that whole summer to win the Cup.”

The textbooks point out that induced drag is minimized by an elliptical (high roach) planform. That makes the ellipse or “Spitfire wing” shape the most efficient outline for a lifting surface, be it wing, keel, or sail. Certainly, sailboards and multihulls have gone heavily in the “fat-head” direction. With the advent of carbon-fiber spars (which Doyle labels “hard not to tune”), masts can now be made stiff enough to stand without a backstay. That, plus refinements in full-length batten technology let monohulls like the e33 benefit from elliptical mainsails and the efficiencies they bring.

“We resisted putting battens in our jib, but a (roller-reefable) triangle didnt give enough punch in light air,” Doyle says. Vertical battens (which make for a better-setting, more-versatile sail) let us add roach for more power.”

The e33s recessed furler with control line led to the helm affords a jib that is elegant and ergonomic as well as efficient.

“Because our sail area is more efficient, we need less of it,” says Doyle. “You can handle our jib without a winch. And our center of pressure is lower. That promotes stability. The J-100, for instance, has a mast thats 7 feet taller than ours.”

Crack off the main, and a lot of the boats sail area goes away. The sheet and traveler let you open (or close) the leech optimally via the top batten. Sails are cut full with easy-to-manage systems like the cunningham to flatten them in a breeze. If you are racing, the Sailtec hydraulic headstay assembly forms a single-point rig adjustment that you can massage puff-by-puff. If you are daysailing, you can set it and forget it.

On Deck

]Not only does the deck take up half the boat, it is unbroken. More comfortable and less silly than the ubiquitous pushpit seats that adorn many of todays auxiliaries, the afterdeck affords room to read, snooze, or veg in security and comfort. If sunbathing were politically correct, you could do it there, too, all without interfering with the steering or working of the boat.

Just forward of the rudder post is a full-width traveler bar. Sited aft where toe-stubbing is no concern, its control lines are nonetheless convenient to the helm. A gracefully laminated gooseneck tiller sweeps from under the traveler forward to the helmsman.

In the center of the cockpit is a raised pod/footrest that houses mainsheet blocks and can accept a table. If you choose to have the available centerline winch, it goes there beneath the head of the tiller. The sturdy molding houses control lines (halyard, jib furler, spinnaker tackline, and self-tacking jibsheet, if you choose that option) and is low enough to be unobtrusive yet substantial enough for foot bracing. Another nice solution.

It doesn’t surprise us that a boat built by a sailmaker should emphasize sailhandling. The gross and fine-tune systems for the main are not afterthoughts. The big blocks have a home in the pod, and the little ones have been incorporated into the main (carbon-fiber) boom. Two-part control for the jib might have been cumbersome, but fairing the blocks for the fine-tuner into a cabintop channel makes the assembly look clean and work well.

Accommodations

Below, youll find “the bare necessities.” Bunks for a cozy family of four, an enclosed head, and cooler complete the list. No galley, no running water, no weight, no worries.

Doyle and his wife, Janet, took the boat on the Eastern Yacht Club cruise. In four nights and five days aboard, she enjoyed “a dry and comfortable cabin with spacious bunks … zero time over a hot stove … and having 18 aboard for cocktails in the cockpit.” Simplified, camping-out cruising has its charms. The e33 can easily provide them.

Performance

The boat has an auxiliary (a 14-horsepower Yanmar diesel with folding prop on a sail drive), but we doubt it will see much use. Open, narrow, light, and maneuverable, the e33 simplifies boathandling (under both sail and power) around docks, moorings, and marinas-an aspect of “performance” that is easily overlooked.

A 2:1 halyard and ball-bearing Ronstan cars for the battens took the strain out of raising the main. With the sail fully hoisted, the cunningham became our prime means of draft control.

The jibs conventional double-sheeting works so well that we wonder why anyone would choose the optional self-tacker. The standard 105-percent jib looks to us more hassle-free and foolproof than the self-tending alternative.

Falling off and running before a moderate souwester out of Marblehead, Mass., we noted how the jib settled into wing-and-wing untended and how comforting it was to have a clear field of vision over the bow. We sat at the rail, the seat, switched sides … there didnt seem to be a bad spot to steer from. There was nothing “corky” about the way it cut the water. There was little wobble as we surged along. Deep, narrow boats have a feel of their own.

Outside the harbor, we lost some of the breeze and picked up a bit of chop as we rounded onto the wind. This is where we expected her to be at her worst: light wind and waves. Did she have the raw sail power to punch through the slop?

With no trial horse in sight and drawing only on seat-of-the-pants approximation, we loosened the headstay and bagged the main a bit. Our acceleration improved as did our speedo numbers. While the e33 lacks the same “power reserve” you might expect from a boat with a taller rig and an overlapping headsail, its ultra-efficient rig and easily driven hull make it more competitive than you might think. An optional Code-O turbocharges the boat in light air.

On the way back to the mooring, the local “harbor hurricane” in the entrance channel bumped the breeze up into the teens. As advertised, an ease of the main and pump on the headstay had us driving through the puffs at better than 8 knots, no hiking necessary. Flat water showed her close-windedness off to advantage; tacking in less than 80 degrees was impressive.

Wending through the crowded mooring field, the e33 was balanced enough to let us bear away without spilling the main, responsive enough to carve tight turns. Several times, we approached from dead downwind and luffed around a moored boat or ball. The narrow hull carries the e33s weight for boatlengths at a time, the jib feathers harmlessly amidships. More than once, we drove to leeward around an obstacle despite a building puff … minimal helm, positive result!

Some critics called her “too much boat” for the average sailor. Others said that only top-notch pros like Doyle could get the most out of her. However, our time on the water convinced us that she is not only a legitimate “performance boat,” but that attaining that performance is sinfully easy.

Conclusions

On the printed page, the profile/sailplan of the e33 emphasizes the contrast between its modern-looking rig and its heritage hull. On the water, that mismatch is minimized to the point that we didnt find it to be a problem.

Though it doesn’t approach the “million dollar” pricetag of some of todays new daysailers, the e33 (with a base price of better than $150,000) is not cheap. But when it comes to quality items like the carbon mast and boom, you get what you pay for.

Indeed, the “trophy daysailer” market is rife with branding, image, and various forms of snob appeal. The e33, on the other hand, makes its pitch on practical grounds. As the marketing literature emphasizes, it is an intelligent, inspired, comprehensive attempt to capture the fun of performance sailing. Thanks to the talents and experience of Doyle and company, it succeeds admirably in doing just that.