So you’ve read our many reports on anchor shanks, and you’re thinking, I wonder what kind of steel my anchor shank is made of? You could go to the maker, but you might find, as we did, that some manufacturers consider this proprietary information-as if the strength of the steel is not worth sharing with the consumer. And then there’s the quality-control issue. In the past, some makers claimed they did not know their anchors were being made with steel that did not meet advertised specifications.

So you decide to find out for yourself.

The only way to truly define steel quality is to use the services of a metallurgical lab, but there is a quick and dirty test that will allow you to roughly estimate the tensile strength and to compare two or more anchors. To do the test, you need five things: a big powerful vice, a pea- or marble-sized ball bearing, a collection of bolts, a micrometer, and a friend. Between the local automotive store and the home-improvement store, you should be able to find the first three. If you own a boat, the last should be pretty easy to come by, too.

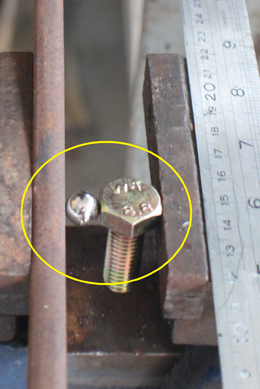

In this test, you are comparing the hardness of a shank to that of steels of a designated hardness used in the sample bolts. The tensile stress of a bolt is defined by markings on the bolt head. These codes are well documented on the websites of most major fastener manufacturers. One we refer to, Appendix A-1 of the Fastenal Technical Guide offers a guide to identifying bolts and their respective tensile strength by using the head markings, but there are plenty of other websites with photos and illustrations. Another option is to obtain scrap steel plate-of a known grade with a hardness and yield strength that is well documented.

To determine the grade of steel, you’ll need to remove a very small area of the galvanizing coating. (Although you can protect these areas with spray-on zinc paint, corrosion can occur more quickly in these areas, which is why I suggest doing this with only old anchors you are not using regularly, or ones you have serious concerns about.) The ball bearing is then sandwiched between the shank in query and the known standard bolt. The three items are then squeezed, with as much load as is possible, in a bench vice. The indentations on the shank and standard sample bolt are compared with a micrometer. The softer metal, with lower yield stress product, will have a larger indentation. If you have enough bolts of varying hardness, you can eventually narrow down the grade of the steel and its tensile strength.

For example, if your anchor shaft loses a battle with a bolt marked 307A on the head, its minimum tensile strength is probably less than 60,000 pounds per square inch or 413 megapascal (MPa), which is the minimum strength for that bolt. This is one of the lowest grades of steel acceptable in construction bolts, and about as strong as the steel used in some of the weakest-shank anchors on the market.

Jonathan Neeves

Remember tensile strength is the load at which failure can be expected to occur, noticeable bending could occur at the point of yield stress, which is lower. For comparison sake, the steel alloy metal plate used in the stronger high-tensile shanks on the market today (ASTM 514) have a minimum nominal tensile strength of about 790 megapascals. Because every anchor maker seems to have a different interpretation of what high-tensile means, there is a wide variation in shank strength, even among high-tensile anchors.

We tried this test with one of the original Mantus anchors on the market. Surprised by the results, we took the anchor to a Lloyds Register-approved metallurgist, who used a Brinell Hardness Tester to determine the tensile strength, which was estimated to be about 530 megapascal, well below what some other makers are using. In the wake of our findings, Mantus expedited its program to upgrade the material used in its shanks. (This is why we do what we do.) It also posted a report, complete with finite element analysis plots of various anchor shanks, on its website comparing the strength of its shafts to those of others. (We have not verified this analysis, but it appears to be carried out without bias.) Owners of the original anchors can contact Mantus about replacement shanks for the cost of shipping. More details on this will appear in the February 2014 issue of Practical Sailor.

We’re still collecting bent anchor stories and following up on consumer complaints about anchors. If you have a story to share, comment below, or send it by email to [email protected].