There’s no question we’re in the middle of a revolution in off-the-grid technology for cruising sailing. Over the past few weeks, I’ve watched three different system overhauls at Salt Creek Marina in St. Petersburg, FL as sailboat owners upgrade their solar panel systems to power nearly all the creature comforts of the home with little or no use of a fuel-powered generator. A combined effort of electrician Andre Cormier of Gulf Nautical and Brian Ford, welder/metal fabricator at The Yacht Rigger, one of the most recent upgrades included dual-sided solar panels, Victron Energy MPPT solar charge controllers, Custom Marine Products LiFePO4 batteries with internal battery management systems, Victron Energy charging and power distribution systems, and Mabru 12-volt air conditioning units. All of these were added to a 40 foot Fontaine Pajot Lucia 40 that was taking advantage of a system-frying lightning strike to upgrade nearly every DC system component.

What was nice about the refits going on is that both Gulf Nautical and the Yacht Rigger, who are swimming in work orders, allow the owners to do many of the more time-consuming, but less technical aspects like mounting control boxes and running the wires between components. Realizing that this was just a snapshot of similar system upgrades of varying scope that are going on in nearly every major cruising port this winter, I figured it was a good time to revive my previous post on making corrosion-proof connections.

Back in 2012, I first put together this link-loaded blog post on the art of taming onboard electrons. I’ve updated it again this week, adding a few links to some of our most recent reports that help fill in some gaps in our coverage. If you’ve got a rewiring or electronics installation project ahead of you, this blog’s for you. Like most of my posts, to get the most out of it, be sure to check out the various links. If there’s something I’ve overlooked or something you’d like to add, just drop me a line at practicalsailor@belvoir.com and I’ll try to include it in our future coverage.

Of all the many maintenance jobs on a boat, DC electrical problems were probably among my favorite to deal with on Tosca—100 times more enjoyable than painting the bottom or cleaning the hull. Except for a few tight spots in the bilge and behind the nav station, all of the wiring and connections on our gaff-rigged ketch were easily accessible, so trouble-shooting required no contortions. It was clean work that called for brain-power, not brawn, and the results were instantly gratifying—a fan that started whirring again, a mast light that came back to life, a solar panel that began pumping amps again. Having easy access to the wire runs and connections made all the difference, something to keep in mind as you rewire your boat, or add new electronics.

Over the years, Practical Sailor has published numerous tests and reports that can help guide a boater through the most common marine electrical problems. In this blog post, Ill introduce the tools you will need for DIY electrical work, recap a couple of the more recent articles with links, and point you to a couple of good resources that will provide more details on repairs and upgrades. One key disclaimer: This post deals only with DC circuits. The AC shore power circuits present a greater risk, and, in my view, are best left to someone who is experienced in that field.

Before diving into any electrical repair project, you’ll want to have the right tools. Fortunately, you’ll need very few-a basic multimeter, a good set of wire-cutters, a quality crimper, and wire stripper for removing the wire insulation for fitting terminals. Two-time circumnavigator Evans Starzinger opened up his toolbox for us back in 2007, revealing just how few tools are required to fix most wiring problems on a boat. Unless you go whole hog on top-of-the-line gear and want a fancy Fluke multimeter, you should be able to put together a kit for about $100-$150.

If a Fluke is too pricey, a $40 multimeter like the one that performed well in our digital multimeter test will suffice for most DC projects. When choosing a crimper, avoid the cheap combination crimper-cutters available in automotive stores. For new installations, or workshop projects that allow plenty of elbow room, look for double-action, double-crimp ratchet crimpers with replaceable, hardened dies for crimping. These meet the industry standard, are relatively inexpensive, and have proven very reliable so long as they are matched with the right sleeves. The drawback to a ratchet crimper is their unwieldiness in tight quarters. For tight spots, the relatively inexpensive Klein 1005, which doubles as a wire-cutter, was a favorite among pros surveyed in our comparison of wire crimpers and strippers.

Ancor, maker of testers favorite budget-priced tool for stripping insulation makes a popular (but not inexpensive) double-action crimper designed for insulated terminal fittings; this makes it much easier to apply the correct amount of compression to insulated terminals. One reader recommended a more reasonably priced crimpers (#22-770) from MCM Electronics, (now Newark element14) which look very similar to those from Ancor. As for wire-cutters, a good set of 8-inch, heavy-duty cutting pliers or lineman’s pliers from Klein tools or something similar offer better leverage and a sharper edge than a cheap set of needle-nose pliers with a cutter.

Tools in hand, were ready to roll. First the wire. To determine whether your wiring has been affected by moisture, cut off the terminal on a suspicious wire and strip back about a half-inch of insulation. If the wire is black, and not shiny pink, then corrosion has begun to migrate up the conductor. You’ll need to strip back the insulation until you find clean, pink copper (or shiny silver in the case of pre-tinned boat cable). Usually, this requires stripping back no more than an inch or so of insulation.

If you find extensive corrosion and need to run new wire, consider paying a little extra for pre-tinned, multi-strand “Boat Cable” labeled “UL 1426 Type III,” which indicates that a wire is finely stranded (Type III) and complies with Underwriters Laboratory (UL) Standard UL 1426. If you are required to run new wiring, it doesn’t have to be painful. To minimize the gymnastics required to run new wire cable through your boat, try some of the hard-won tips on rewiring offered by contributor Bill Bishop, author of the Marine Installer’s Rant blog.

We found that THHN machine wire (available at home supply stores like Home Depot, Lowes, etc.) held up just as well as tinned wire in our marine wire corrosion test, but if you buy in bulk, tinned boat cable is only slightly more expensive, offers better corrosion protection, and will add to the resale value to your boat. Pacer and Ancor are leading wire brands among boatbuilders. Before buying, you will want to refer to the American Boat and Yacht Council’s wire-sizing guide to determine what gauge (thickness) of wire is adequate to carry the anticipated current. Don’t assume the existing wire was the correct gauge.

Chances are, the wire is still in good shape. As we found in our test of marine electrical wire, the key to durability is a good, tight connection at terminals. In fact, copper-strand wire without the protective marine coating of tin can last for years, if the terminals are well-protected against oxidation. That we had no crimp failures in our wire-test torture chamber speaks volumes for a good tight crimp, in which the strands and the terminal are effectively welded together by the pressure of the crimp.

Most of the terminal fittings for our wire test were tinned copper fittings made by Ancor (ring crimp connectors and terminal blocks) or Ideal (heat-sealed crimp connectors and push-on connectors). For main supply cables, Cormier recommends the heavy-duty connectors from South Carolina-based FTZ Industries, which he says are far superior to the others on the market. Standard automotive crimp connectors don’t do the job. They leave the wire ends exposed to moisture, and eventually corrosion will begin at the terminal and migrate into the conductor as the moisture tracks up the wire under the insulation via capillary action. By using heat-shrink crimp terminals or adhesive-lined heat-shrink tubing on conventional crimp connectors, you can effectively seal the ends of all the wire on your boat. (A good online source for a variety of heat shrink products is www.nationalstandardparts.com.) Watertight integrity is especially important in wet areas such as the bilge. If you are dealing with the tiny wires common to marine electronics wiring harnesses, make sure you choose high quality Eurostrips that are less likely to damage the wire strands. A proper splice is often more secure than any mechanical fastener. As our testing showed, simple heat shrink seals—without any splicing—are not worth the trouble.

What about protective sprays or coatings? Twice, Practical Sailor looked at anti-corrosion sprays suitable for wire terminals. In 2007, we looked the best anti-corrosion spray treatments for electrical equipment, and our long-term wire test compared protected and unprotected terminals. Bottom line: These products will help, but a strong, tight terminal connection is the first priority.

For more details on using dialectric grease to make tight connections, Ralph Naranjo offered this tips in our Mailport section. Charlie Wing’s Boatowner’s Illustrated Electrical Handbook also guides you through the steps. For more advanced troubleshooting or installation projects, Ed Sherman’s textbook Advanced Marine Electrics and Electronics Troubleshooting is an excellent guide. Nigel Calder’s excellent Boatowner’s Mechanical and Electrical Handbook also offers good advice on this and many other topics related to the electrical system. You’ll also find related DIY books, including our five-volume ebook on marine electrical systems in Practical Sailors online bookstore.

When rewiring or replacing wire terminals, here are some key points to keep in mind:

Match the Lug Terminal Size to the Cable Size. It matters. If you use too large a lug terminal, the air pockets or voids in the crimped joint (especially when using coarse stranded wire) will increase voltage resistance. Resistance equals heat, which in turn will lead to a faster rate of corrosion at your terminal end. Never “trim off” strands of wire because the lug terminal you are using is too small to accept your wire. The American Boat and Yacht Council (ABYC) standards state that wiring connections shall be designed and installed to make mechanical and electrical joints without damage to the conductors.

Rotten to the Core: The wire that you are terminating must be completely free of corrosion and oxidation. If internally the wire is black or green in color, you must cut back until you find virgin copper, or consider replacing the wire (with tinned wire). The lug terminal must also be free of oxidation. If your spare lugs were stored wet, replace them. The most common problem on a boat is failure of the electrical system.

Crimp Tip: Make sure that the strands of your wire don’t extend too far out the front of the lug and into the terminals eye or spade contact area. When applying pressure with your crimp tool to the lug terminal, make sure that you apply enough pressure so that good metal-to-metal contact occurs. The goal here, in addition to forming a good mechanical contact, is to break down the oxides that build up on the inside of the terminal lug. Unless a good metal-to-metal contact occurs, the oxides will not be broken down and resistance will build up inside the terminal. Check your crimp by giving the wire a good tug.

Plastic Not Welcome Here: The best-insulated lug terminals are those with nylon insulator sleeves. Nylon resists UV, gasoline, and oil. Unlike the cheaper vinyl and plastic insulator sleeves, nylon will not punch through or crack and fall apart when the squeeze gets applied. When installing new or replacement equipment, check the lugs supplied by the manufacturer. If they’re not nylon, consider replacing them with a better quality, or plan on using shrink tubing to dress up the connections post crimp.

Solder vs. Crimp: National Marine Electronics Association standards state that solder shall not be the sole means of mechanical connection in any circuit (with the exception of certain-length ship’s battery cables). If inclined to add solder to a lug terminal, solder it after you apply the crimp. A good solder joint is bright and shiny.

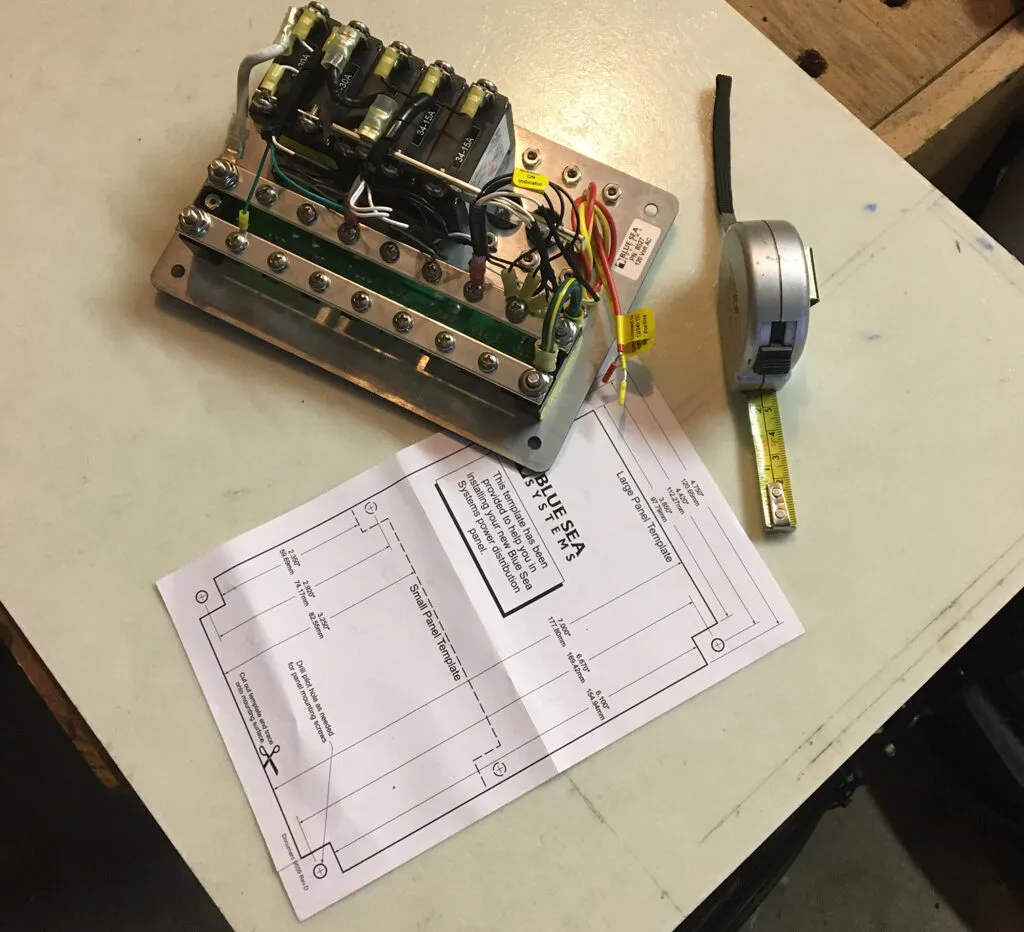

If you do find that you need a whole new electrical panel, check out the lineup from Blue Seas, which has consistently done well in our tests of DC electrical panels.

Finally, if you are planning to upgrade of your boat’s electrical system, our five-volume ebook Marine Electrical Systems consolidates many of the above-cited reports and dozens of others from our archives covering everything from conventional wet-cell batteries to wind generators. This book is continually being updated, so as we test new technology like the components mentioned at the top of this article, purchasers of the ebook will be notified, and able to download the updates at no extra cost.

I have a Perry 59′ sailboat with 12vdc, 24vdc and 110vac via both shorepower and a 4kw inverter. We’ve never had electrical problems with connectors when installed, but often problems getting a good crimp. Often times we have needed to splice a small wire, like 20 ga, to the manufacturer’s 14ga usually when installing LED lights, for example. For the small wire side, I often fold over the 20 ga to double it up. From experience, I’ve found that a vice-grips work much better than a crimper to get the strongest connection. They’re easy to adjust to get just the right squeeze on the thin wire. Our boat will be 17 in Feb ’21, and is connected better now than when new!

you can purchase special butt connectors that are designed to connect different gauge wires together. They would be ideal for connecting 14ga to 20ga. A good ratchet crimper is superior to vise grips or pliers.

An article on sanding out and re-coating (painting) small areas of corrosion on aluminum would be very useful.

For cleaning up corroded terminals and lugs I’ve found polishing bobs to be useful (which fit on a dremel tool). Much easier than using sand paper or a file and do a superior job in confined/hard to get to areas. The terminals are like new shinny when you’re done. The bobs are rubber with a silicon carbide or aluminum oxide abrasive embedded that cuts quickly with light pressure and available in a variety of grits.

Thank you for letting us know about this!

I’ve had issues and objections with Mr. Nicholson’s various writings here on tinned vs. bare copper wiring and termination since 2008 when he identified tinned wire as a ‘myth’ to be busted on this site.

The first and worst of the oversights leading to his misinformed view is lack of any attention or even acknowledgement of the issues around vibration and thermal heating/cooling cycles due to ‘I-squared-R’ heating as current loads are applied.

Vibration: The reason UL-1426 specifies a very high number of strands per circular mil is to ensure that terminated wire connections do not fail under the high-vibration environments that power boats (and sailing vessels, to a lesser extent) are subjected to over their long lifetimes. Finely stranded wire is FAR less susceptible to failure or degradation in general and especially critical where wires are terminated at bus bars, overcurrent devices and electrical panels. Author Nicholson’s writings and testing suggest he has been completely unaware of the role of vibration in causing failure in marine wiring terminations.

Thermal Dynamics of I-squared-R Heating: UL-1426, ABYC, the CFR and Military all require insulation temperatures to be specified, and insulation ratings are the second most important factor in determining the end-to-end ampacity of a circuit in ANY environment. All electrical conductors have some resistance (R) and therefore generate exponentially increasing heat as the current (I) increases linearly; the formula for heat loss in a wire is the current SQUARED times the resistance in the circuit, hence the formula is “I-squared-R”. CRITICALLY; (a) the electrical resistance in any circuit is typically concentrated at the termination points and (b) therefore thermal expansion and contraction of the conductive components of terminations (lugs, crimps, bus terminals, etc) are particularly vulnerable to failure from thermal expansion/contraction cycles as circuits are dynamically loaded/unloaded hundreds of THOUSAND times over the lifetime of a boat. As with vibration, Nicholson’s writings and testing suggest he has been completely unaware of the role of thermal expansion/contraction of wiring terminations as a primary cause of failure over time.

Summary: Nicholson’s purely static testing methodologies produce meaningless results because he does not recognize the principles of ALT (accelerated life testing) and account for ALL the relevant environmental conditions, especially those that are dynamic in nature. To improve it, Nicholson should include vibration (shake table) at various frequencies and continuous loading/unloading of each termination up to at least 150% of the ampacity of the wiring.

Nicholson’s uninformed viewpoint and overly simplistic testing methodologies lead him and his readers to the cynical conclusion that the sellers of tinned copper wiring are propagating a marketing-driven, profit-motivated myth. It’s time to stop this and start over again by actually understanding the problem.

All of Mr. Nicholson’s writings on this topic, starting with his “tinned wire myth busting” in 2008, should be removed from this site.

In light of the comment above, the critical and indisputable characterstic of Tinned Copper wiring aboard boats (and all similar environments) is that oxides of Tin are electrically conductive — as good as unoxididized Copper. In contrast, oxides of Copper are non-conductive at best and at worst can present characteristics of a SEMI-conductor, making in-situ testing of circuits difficult even with the most sophisticated equipment. Time-domain reflectometers (TDR) and high-impedance ohmmeters are notoriously ineffective in identifying failed, failing or intermittent problems caused by oxidized copper at termination points.