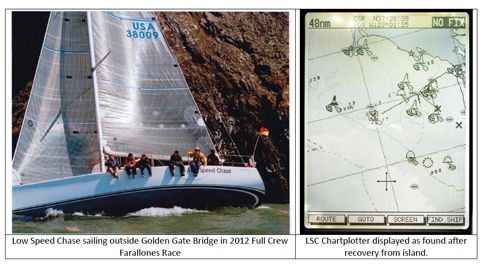

It seems somehow appropriate that today, as I hopscotch among the islands of Irelands western coast, U.S. Sailing has released its final report on the fate of the crew of Low Speed Chase. The comprehensive report, available for download at the U.S. Sailing website, covers in great detail the factors that led to the deaths of five sailors on April 14 during the Full Crew Farallones Race out of San Francisco, Calif.

The report confirms the bare facts of the accident that have already been reported, as summarized in the U.S. Sailing press release issued Aug. 6:

The crew of eight aboard Low Speed Chase encountered larger than average breaking waves when rounding Maintop Island, the northwest point of Southeast Farallon Island. These waves capsized the vessel, a Sydney 38, and drove it onto the rocky shore. Seven of the eight crew members were thrown from the boat into the water.Only two of those sailors in the water made it to shore and survived.

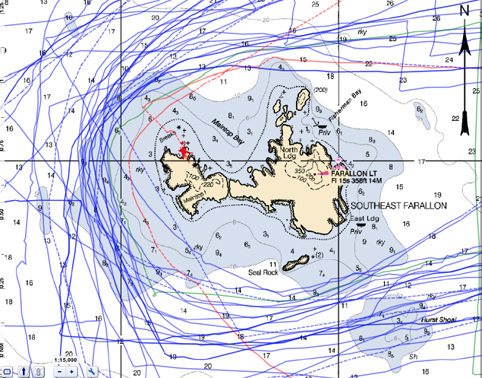

The panels determination regarding the principal cause of the accident is also consistent with early theories, as the release states: The primary cause of the capsizing was due to the course sailed by Low Speed Chase, which took them across a shoal area where breaking waves could be expected.

The panel is careful not to point any fingers in its conclusions, but it clearly raises questions about how much responsibility race organizers and management officials have for the safety of its participants, and it reiterates a need for more consistent safety guidelines and training among racers and race organizers. According to the press release, the accident has already prompted several changes to race management practices, and a new organizing body, NorCal Ocean Racing Council (NorCal ORC), has been formed to develop new safety guidelines for races in Northern California.

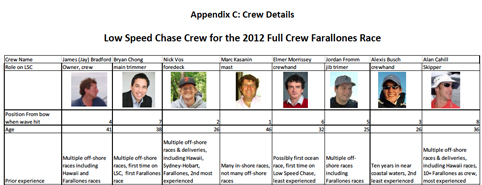

Racing sailors will be interested in the in-depth section regarding the experience and management style of the skipper and crew aboard Low Speed Chase, as well as the apparent communication lapses as the tragedy unfolded. The areas of the report most relevant to cruising sailors are those involving safety gear such as tethers and harnesses and personal floatation devices (PFDs), emergency communications (including distress signaling), and the personal testimonies of survivors and witnesses, which offer a graphic description of the chaos that ensues when a boat founders in surf on a rocky shore.

I was pleased to see that the panel went into scrupulous detail regarding the personal safety equipment used by each sailor aboard Low Speed Chase, their location on the boat, and as much as could be determined regarding their fate. The details of the GPS tracks of Low Speed Chase and 13 other competitors, superimposed on Low Speed Chases route the previous year-even closer to the rocks than in 2012-was particularly telling.

Ive yet had time to read the report closely, but a few things came to my attention:

– Of 10 other boats participating the race that were inspected by the panel after the accident, only two were equipped with the jacklines for clipping in, which are required by race rules.

– Resolution of the position of Low Speed Chases EPIRB (which was not equipped with an internal GPS receiver) took 40 minutes, by which time a search for survivors was underway.

– Organizers of the event did not comply with the requirements for the event, as stipulated in the Coast Guard permit.

– VHF communications between the race committee, racers, and the Coast Guard was hampered by poor reception, wind, and garbled messages. Calls from the race committee to the fleet confirming the accident went unanswered.

– Inconsistencies in race registration information made it difficult for the Coast Guard to confirm how many people were on board Low Speed Chase.

– None of the crewmembers aboard Low Speed Chase were clipped in, and only three were wearing their tethers.

For me, however, it is not so much the detailed analysis that resonates strongest, but a stark comment by survivor Bryan Chong, who believes more of his crewmates would have survived if they had been clipped in with their tethers. (The boat was washed onto the rocks with the hull intact.)

Id reached a level of comfort where Id only tether at night, when using the head off the back of the boat or when conditions were really wild. Its simply a bad habit that formed due to a false sense of security in the ocean.

It is this same false sense of security that Irish author J.M. Synge warned about more than 100 years ago in his classic journal of life on the Irish coast, The Aran Islands: A man who is not afraid of the sea will soon be drowned.

Looking out over the surf pounding upon Arranmore Island today-much the same as it did on the Farallones last April-his words ring truer than ever.