When you’ve tested anchors as long as Practical Sailor has, you feel pressed to explore unconventional arrangements that others advocate-particularly if the advocates include experienced sailors and a major anchor manufacturer. Such is the case with the tandem anchor setup, in which two anchors are connected to a single rode leading to the boat. The anchoring system is widely discussed on online sites catering to cruisers and is endorsed by at least one manufacturer, Rocna, which has encouraged tandem anchoring with the placement of a special hole at the base of the Rocna shank for shackling on a second rode and anchor.

In our view, tandem anchor rigs are only useful for exceptional situations in which a conventional anchoring setup (one anchor on one rode) or a twin anchor arrangement (two anchors set on separate rodes) wont work. If you are consistently having problems setting your primary anchor, rather than immediately experimenting with tandem anchors, or other unconventional approaches, we recommend that you review basic practices and consider getting a larger or different style anchor that suits your cruising grounds. On our website, youll find multiple anchor tests and other resources, including a four-volume e-book on anchoring and mooring, to help you choose a good anchor. This report is aimed at sailors who face unusual circumstances that require creative solutions, such as those encountered by the test boat we used for this evaluation.

The PDQ 32 catamaran used for this test cruises year-round in Chesapeake Bay, Va., often overnighting in anchorages that have proven very difficult holding ground for conventional single-anchor setups (see PS February 2015, Anchoring in Squishy Bottoms online). A concern with such anchorages is that one anchor style that has proven effective for these bottoms, the Danforth-style anchor with a large fluke area, does not reset as well as other styles. If the wind veers and the boat starts dragging quickly-in a squall for example-rather than bounce along the bottom and perhaps reset, a lightweight, Danforth-style anchor can even begin to plane above the bottom if theres not enough chain weighing it down. (Heavy chain, however, can pose a different problem in very soft mud, sinking below the shank and upsetting the anchor geometry, as discussed in the February 2015 report.)

Meanwhile, conventional claw, plow, or scoop anchors can drag in soft bottoms at loads as low as 400 pounds. In a tandem system, as some people suggest, each anchor style compliments the other-the conventional primary anchor weighs down the Danforth-style secondary, and the secondary Danforth-style stops or slows the dragging of the conventional anchor.

Over the years, the PDQs owner, frequent PS contributor Drew Frye, has had success combining the soft-bottom holding power of a Danforth-style anchor with a scoop or claw-type anchor by using a tandem anchor setup. In this setup, the primary anchor is usually a scoop or claw-type anchor on an all-chain rode and the secondary anchor is a Danforth-style anchor on a nylon rode with chain leader. The two anchors are usually set in an asymmetrical V toward the anticipated wind direction, with the rode for the secondary anchor (about 50 to 100 feet long, depending on the depth) joined to the primary rode below the water.

This reduces the headaches of attaching two distinct rodes to the PDQs long bridle/snubber and improves holding in relatively shallow bottoms-but it can introduce other complications, especially upon retrieval. The system may not be of any benefit in more common anchoring scenarios, harder bottoms, or deeper water (30 feet or more), and it will hold even less appeal to owners of monohulls with foredecks that are well-equipped to simultaneously accommodate two different anchors and rodes.

Although Frye has had success with the system in storm-force winds, it is not our recommended arrangement for a hurricane mooring or anchoring in a tropical storm, which requires more substantial ground tackle and more specialized gear. Tropical storm anchoring was addressed in Tropical Storm Do’s and Don’ts.

What We Tested

In Part I of this series (PS August 2016), we tested 2-pound anchors in a variety of bottoms and rigging geometries. We confirmed that holding power and dragging behavior in soft bottoms was scalable to larger anchors, and that asymmetrical tandem setups using a Danforth-style anchor as the secondary anchor showed the most promise.

Here, in Part II, we turn to full-size anchors, focusing on the practical aspects of tandem rigs and observing their performance. This study required dozens of hours of testing in the field, deploying various tandem rigs with full-size anchors in a variety of bottoms. The aim of the project was to develop a two-anchor system that could be easily deployed from the boat by someone of below-average size and strength.

The study focused on just two tandem setups: the tandem in-line and asymmetrical tandem V. The evaluation took place over several seasons, during which our tester tried various combinations of three types of anchors: scoop (a 35-pound Manson Supreme and a 35-pound Rocna), plow (25-pound Delta and 12-pound Northill Utility), and pivoting-fluke (10-pound Fortress FX-16).

When we describe tandem rigs in this article, the anchor closest to the boat is referred to as the primary anchor; it is deployed on the primary anchor rode. The anchor that is set farther away is called the secondary anchor-even if it happens to be the boats usual main (primary) anchor. The secondary anchor rode attaches the secondary anchor to the primary anchor rode or to the primary anchor itself. A tripping hole is the hole near the anchors fluke that is used for releasing an anchor from the bottom. A tandem hole is the hole located near the fluke of the shank; it is dedicated to attaching a secondary rode. An off-axis load is one that is not aligned with the shank of an anchor.

In-line Tandem Testing

The in-line tandem arrangement features a secondary anchor set in-line in front of the primary, with its rode attached to a tandem hole in the primary anchor. This is the system that Rocna suggests; however, Spade Anchors, which makes a scoop-style anchor similar to the Rocna, strongly advises against adding a tandem hole and using its anchors this way.

Our test setup included a 25-pound Delta anchor secured to a tandem hole on a 35-pound Rocna; a Fortress FX-16 secured to the tandem hole of a 35-pound Manson Supreme (we drilled a tandem hole for testing); and a 15-pound Northill secured to the tandem hole of a 35-pound Manson Supreme. We used Amsteel for the secondary rode for ease of handling during testing; chain is preferred for abrasion resistance.

The tandem in-line setup included about one boat length of Amsteel, attached at one end to the secondary anchor, and attached at the other end to the tandem hole in the primary anchor. To deploy the secondary anchor, we attached a retrieval line to the same shackle as the rode and lowered it down. This way, we could control the anchors orientation on the bottom and prevented it from snagging on its own rode.

Once the secondary rode had a few feet of slack in it, we deployed the primary anchor, backing down as usual, making sure that a few feet of slack remained in the secondary rode when the primary anchor hit the bottom. The primary also had a retrieval line attached to it. We then backed down on 20:1 scope and set hard (240 pounds thrust from twin Yamaha 9.9-horsepower, high-thrust outboards). Our findings were disappointing:

-Delta secondary / Rocna primary: The Rocna only partially set two out of three times.

-Fortress secondary / Manson primary: Twice the Fortress did not set at all, and the one time it did, the Manson was lifted from the bottom and deposited upside down in the mud.

-Northill secondary / Manson primary: On three out of five deployments on sand, the smaller Northill bit first and lifted the Manson clear out of the sand as power was applied. In soft mud, the two set well, until the wind shifted overnight, causing both to lose their deep sets.

-Limited testing in rocky bottoms indicated that an in-line anchor setup holds some promise here, but with a different anchor combination. We will continue to look into this.

Bottom line: Every in-line combination was a glaring failure on sand and soft bottoms, worse than a single anchor. Our field results confirmed what our small-scale testing had found.

Asymmetric V-Tandem

One advantage of V-tandem setups is that you set each anchor individually. To simplify setting and retrieval, Frye keeps a 50-foot rode (with spliced eyes on both ends) on his secondary anchor, a Fortress FX-16, and can extend this with an identical 50-foot extension, if he wants it farther away. He has a third 50-foot line with a spliced eye that he uses for setting and retrieving the secondary anchor and rode. If the wind direction is constant, both rodes should be loaded, but if a shift is expected, leaving some slack in the soon-to-be windward rode will help the anchors share the work.

If you initially plan to anchor with two hooks, you can lay the asymmetrical V in one pass. Attach both the secondary rode and the 50 feet of extension rode to the secondary anchor. Lower the secondary anchor, back down one boat length, and then lower the primary. With each anchor cleated to the boat independently via its own rode (and extensions, in the case of the secondary), back down to set each anchor independently, setting one at a time at full scope.

Once each anchor is set, pull up the anchors to short scope until you can reach where the extension line joins the secondary rode. Join the secondary rode to the primary rode (Frye uses a Dyneema soft shackle to make this attachment), remove the extension line, drift back to normal scope, and attach the rode to your boats bridle or snubber. When the wind shifts in either direction, the primary anchor will feel the initial load, and as it begins to set deeper or to drag, the secondary will take up load as well, slowly turning to meet the new force. If high winds have already set in, the process becomes more complicated.

The fastest deployment when already anchored is to come up on short scope (Fryes primary anchor is most often a 35-pound Manson Supreme), veer the boat toward the side of the strongest expected wind using the engine, lower the back-up anchor (Fortress FX-16) from the bow, and then back down to 7:1 scope based upon this new anchor, and set it. In this way, the second anchor does not need to be rowed out.

The disadvantage to this approach-sometimes critical-is that you need plenty of room to ease back farther to get enough scope.

Alternatively, so long as the anchorage is still relatively calm, you can take the Fortress secondary out by dinghy (either straight forward or in the direction of an anticipated shift), about one boat length farther than the main anchor. See the accompanying Step-by-Step: Setting a V-tandem Anchor Rig.

Like any anchoring arrangement, the tandem setup will benefit greatly from an appropriately sized snubber (see PS March 2016 online).

Conclusion

Our small-scale anchor tests (PS August 2016) proved very useful. The calculated data correlated with what we found in testing full-scale anchors, and the anchors behavior was effectively identical. The most promising tandem arrangement was the V-tandem rig using a scoop-style anchor (35-pound Mantus) as a primary and a Danforth-style anchor (Fortress FX-16) as the secondary, so well focus on those numbers here.

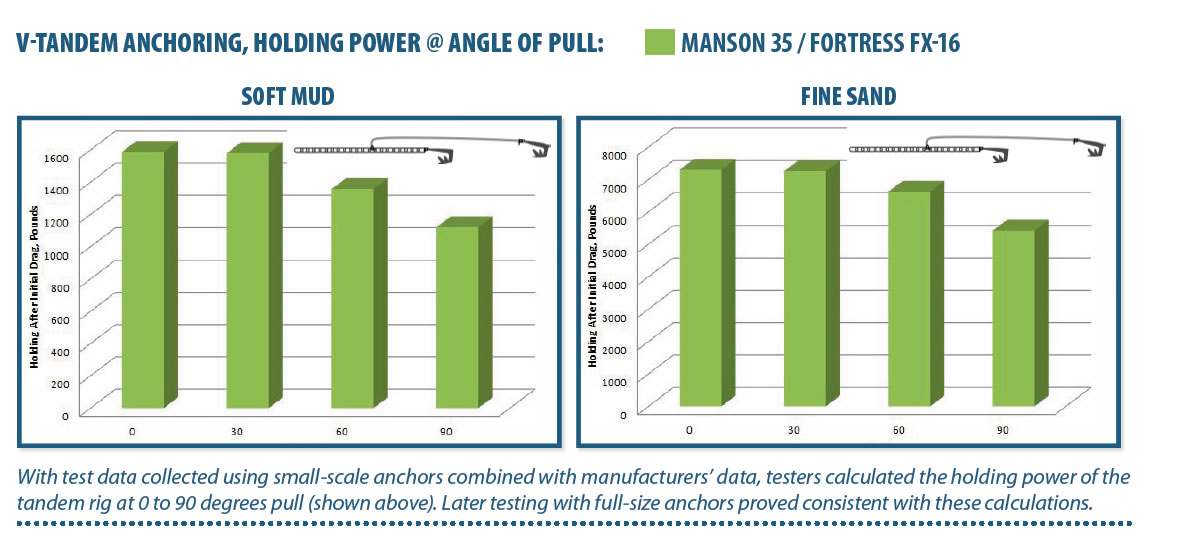

In the small-scale testing with a scoop-style primary anchor (2-pound Mantus) and Danforth-style secondary anchor (2-pound Guardian), the asymmetric V tandem held about 140 pounds in soft mud through a range of angles. This data, combined with what we learned in full-size testing, allowed us to estimate the holding power of the full-size Mantus/Fortress combination in the Solomons Island test location, the subject of our February 2015 report.

At that test site, most scoop-style anchors dragged at loads less than 700 pounds. By our estimation, an asymmetric tandem incorporating an FX-16 (primary) and a Manson 35 (secondary) should hold up to about 1,600 pounds. Indeed, during our testing with this rig in a similar location, we measured a maximum sustained rode tension of 1,200 pounds-well beyond the 680-pound average values for the Mantus alone in the Solomons Island test. When we examined the anchors underwater, we noted that they had rotated to meet the wind shift, just as they had in the small-scale testing.

Probably the most important lesson from this test is that in very soft mud bottoms, there is no such thing as a set anchor. In these bottoms, all anchors move when pushed to their limits. No anchor rig-single-line, asymmetric V-tandem, or in-line-can fully prevent this. With each wind shift, the pressure becomes greater on one anchor, it adjusts, and the rig moves. Bottom condition is the most essential variable. If your anchor refuses to set, rather than adding another anchor, often your best approach is to seek better holding ground.

With test data collected using small-scale anchors combined with manufacturers data, testers calculated the holding power of the tandem rig at 0 to 90 degrees pull (shown above). Later testing with full-size anchors proved consistent with these calculations.

By far, the easiest method to set an asymmetrical V-tandem anchor rig is deploying and setting each anchor individually from the boat as described in the accompanying article, and then attaching the secondary rode to the primary rode at the bow roller (as shown in photo 6, above) before letting out full scope. The accompanying photos show deployment from a dinghy, which is only more convenient in calm conditions when the main anchor is already well set.

- The secondary anchor and 50 feet of secondary rode, with an eyesplice at the bitter end, is kept coiled with the soft shackle used to attach the secondary rode to the primary rode (see photos 4 and 5). An extension rode, also coiled with a soft shackle, can be attached to the secondary rode when more scope is required. A retrieval line (about 50 feet long) is also used in this process. All of these components are easy to store in the lazarette.

- The secondary anchor and secondary rode (and extension, if needed) are loaded into the dinghy. It makes sense to keep the secondary anchor in the stern locker, since it is more often set from the dinghy or from the stern; this also keeps the extra anchor off the bow. Once most of the rode is loaded in the dinghy, attach the bitter end of the 50-foot-long secondary rode (and a 50-foot extension, if desired) to the boat at the bow roller. Row or motor toward the desired spot, trailing the rode behind until you have run out of rode. You can then return to the boat and set the secondary anchor from the boat. Once it is set, you can return to the dinghy and attach the secondary rode to the primary rode.

- With the secondary rode set, the primary anchor has been pulled up to short scope and the secondary rode is attached to the primary rode with a soft shackle just below the bridle/snubber. (Never put the rode over your lap, this was for illustration purposes only.)

- It is helpful to use a carabiner to clip the secondary rode to the primary rode while you are attaching the soft shackle. The carabiner holds the chain in place while you thread the soft shackle onto the all-chain primary rode. The same thing can be done when deploying or retrieving from the bow (photo 6).

- The soft shackle needs to be relatively long. This makes it easier to attach.

- A carabiner clips the retrieval line to the secondary rode before removing the soft shackle and each rode is hauled up in any order. When setting from the boat, the retrieval line is used to set the secondary anchor, and the process is reversed; the retrieval line is unclipped, and scope is let out.

Hi. I beg to differ ! As a CASA Yachtmaster and ex liveaboard skipper on a 70ft steel charter schooner in the Leewards, etc. etc., I have regularly used in-line tandem anchors. Our bower was perfectly adequate, but the way I tandem-anchor is so simple, I just did it all the time ; why not be even safer ? Especially with guests aboard. I drop the bower as normal, run out chain till it touches, then simply shackle the second anchor to the chain by its usual ring, and continue reversing and paying out chain to three times water depth. Give a half-power and several seconds’ tug, then continue reversing until there’s five times depth paid out. Then build up engine power to very nearly full. and shut down. I promise you, it has NEVER dragged ! My main problem with your suggestions is your attaching the first anchor directly to the head [fluke end] of the second. I see that as a recipe for trouble. You may say that my method has the same effect ; but it does not. My way, the two anchors retain a degree of independence, but your way one anchor is pulling directly on the working end of the other. No wonder your results were unsatisfactory ! On the subject of the ‘Bahamian moor’ (two anchors at 45 degrees) ; this requires too much space in many situations ; it creates twice the anchor-fouling hazards in a crowded anchorage, or when there are inexperienced skippers (who may expect you to be lying head-to a single anchor) anchoring nearby ; and only one anchor is ever holding the boat. So why bother with it unless you are experiencing wind shifts and need anchor-holding from two directions ? A final brief-as-possible note, some details omitted : Anchored in Brasil in a steel thirty-footer, with an island too close under my lee after a sudden wind shift and the weather deteriorating very quickly ; I laid my bower [big CQR], then added the kedge [slightly lighter Danforth] then on the same chain, I added my dinghy anchor. The wind and waves did the digging-in for me. We were stuck there, as were several other boats, our engine power inadequate for a safe escape to weather in the already-high short waves. All the other boats dragged and were skilful and lucky enough to motor-sail (storm canvas) out of it. We stayed. I added a two-ton nylon rope snubber to reduce the repeated heavy shocks on the chain. During the night I had to replace it several times, when the waves threw us back so hard against the chain that the force snapped the snubber rope [There was no chafe, in case you ask !]. When it had calmed down enough to leave, I weighed. The dinghy anchor was a twisted wreck. The shaft of the Danforth was bent 30 degrees. The CQR was perfect. According to my bearings, we hadn’t shifted at all. I have never experienced conditions at anchor which were worse than that. I am therefore satisfied that in-line tandem anchoring works ! Sincere thanks for all the generously free articles, which I always read. This is offered as a helpful contribution, not as a criticism. Rob Neal.

We had mixed experiences with an inline tandem set up on a charter in Belize. We were on a 35′ monohull. After provisioning and ready to set off we hauled up the anchor rode only to discover two CQRs hooked together in-line. This was with my wife and two young kids and no windlass. So the first was up in the bow roller while the second hung down on another 8 feet of chain. I managed to eventually get the second on board and started scratching my head. It has been a while so I don’t recall the details of what the (second tier) charter company said. I do recall in the briefing that they said they had previous charters on this and other boats drag. Some of the anchorages are deep with not a lot of room for full scope so this was likely their solution. I guess this was their solution. I think we used it the first night where we were in a deep anchorage with less room than adequate scope would have be to close to shallows. but after that just stowed the second in a lazerette or somewhere out of the way.

On our own current boat we have a Spade which has always been great even in reversing currents, with or without opposing winds. I have a Fortress as a secondary and will keep this article in mind and perhaps practice the asym tandem-V in case a situation arises.

Thanks for the article,

Harry

We arrived in Pago Pago (American Samoa) in about 25 knots of wind and the bottom was so foul that we couldn’t get our 30-kg Bruce anchor to hold. The anchorage for visiting yachts was crowded and small. Five times we deployed our heretofore-trusty Bruce but it wasn’t until we shackled 50’ of 3/8” hi-test chain to the 30-kg Bruce and a 20-kg Bruce to the other end of the chain that we were able to back down at our usual RPMs and not drag. We stayed put for three weeks of reinforced trade winds.

The only other time we successfully used in-line tandem anchoring was in the northern Bahamas where our Bruce couldn’t penetrate through the grassy bottom. Having the two anchors down plus a lot of scope was good enough to hold us through some significant blows.

Fair winds and calm seas.

The problem you had with the inline tandem method was that you attached the anchor furthest from the boat to the trip hole of the closest anchor. Anchors are meant to set from the ring end and so every time you pulled, the furthest anchor tripped the closest anchor.