Boat buying is an exciting, maddening exercise that can test the tolerance of even the most patient sailor. Much of the maddening part has to do with trying to ferret out a boat’s problems before buying (and making them your own). Obviously, you should consult a reputable surveyor prior to purchase, but who can afford to have every promising boat surveyed?

The easiest way to narrow down the list of potential deals is by doing your own pre-survey inspection. Below are some of the major areas of boat inspection any buyer would want to become intimate with, as well as some common problems associated with each.

ENGINE

As the single most expensive piece of gear onboard, the engine deserves particular scrutiny. It is a hard lesson to learn that after purchasing that deal of a lifetime, the boat requires an engine rebuild or replacement.

How an engine looks can offer valuable clues about its overall condition. That’s not to say a shiny, seemingly new engine will be trouble free, but if it’s a real mess on the outside, chances are the owner hasn’t exactly been a stickler for regularly scheduled maintenance.

Start by looking for obvious problems such as leaks, excessive rust, broken or missing components, and other signs of neglect. For freshwater-cooled systems, check the coolant level and properties. Lack of antifreeze should raise red flags (due to possible leaks) as should coolant with a rusty color or an unusual amount of solids.

A lot can be told by simply pulling the dipstick and checking the oil. A slightly low level might be OK, but higher than normal levels could indicate trouble, particularly if milky or frothy; both are an indication that water, antifreeze, or transmission fluid is present, signs you could be facing anything from a blown gasket to a cracked block.

Rub a little engine oil between your fingers. If it feels abrasive or has a burnt odor, be concerned about bearing wear; however, it could also simply mean the oil hasn’t been changed regularly. Wipe the dipstick on a clean white cloth or napkin. Oil thats thick initially, but then starts to spread out over the cloth is an indication of fuel contamination.

Taking oil samples to a lab for testing is a more scientific way to analyze oil condition, but it’s normally most useful in tracking issues over the engine’s lifetime, rather than for spot-checking. Still, a one-shot oil analysis can show unusual wear and the presence of water, antifreeze or diesel fuel. Think of it as a blood test for the engine—it may not predict a heart attack but it can indicate the high cholesterol that could lead to engine failure.

As for transmissions and reduction gears, dark and sluggish fluid or oil with a burned smell may indicate drive cone problems and a costly rebuild in the near future. After running the engine in gear a bit, use the dipstick to get a transmission fluid sample. Put this on a piece of paper and inspect it under a bright light or in direct sunlight for metallic specks—a sign of significant transmission wear. Inserting a long, thin magnet (the kind mechanics use to retrieve dropped bolts) through the dipstick opening and sweeping the bottom of the gearbox may produce interesting results as well.

Note how difficult the engine is to start. Depending on whether it’s gas or diesel, hard starting could be a sign of weak batteries, faulty plugs or even a bad fuel pump.

Does it run smoothly at idle and under load, or does it idle unevenly and stall out when placed in gear? Rough running can be caused by anything from clogged fuel filters to compression problems, and engines idling at more than 800 rpm may have been intentionally set to idle high to mask problems.

Verify proper oil pressure and operating temperature while the engine is running. Low oil pressure could be due to anything from faulty oil pumps to cam bearing failure. High water temperatures may be something as simple as a bad impeller, but could also be caused by corroded manifolds or exhaust risers.

Finally, read the smoke signals the engine is sending. A well-maintained engine may smoke when initially cranked or while idling, but not when warmed up or under load. Smoke color can also provide an indication of problems (blue for burning oil, black for incomplete combustion, white for water vapor, etc.).

Bottom line: Remember that hour meters mean nothing (they can easily be swapped out by an unscrupulous seller) and that an owner should eagerly provide invoices if claiming overhauls or major work has been done. Engines are a big-ticket item, so always weigh the cost of repair or replacement versus walking away.

SOFT DECKS

Water intrusion into cored decking likely causes more boat damage every year than sinkings, groundings and fires combined. Cored construction simply describes an inner and outer skin of fiberglass with some other material sandwiched between them. Most decks will be cored, typically with end-grain balsa, plywood or maybe one of the more high-tech foam variations.

The prime directive with cored construction is keeping water out. Wet wood coring can rot, which allows the cored deck to separate and drastically reduces its structural integrity. Long-term water exposure causes problems with foam-cored decks as well—core separation, freeze damage (due to expansion and contraction) and even disintegration in some cases.

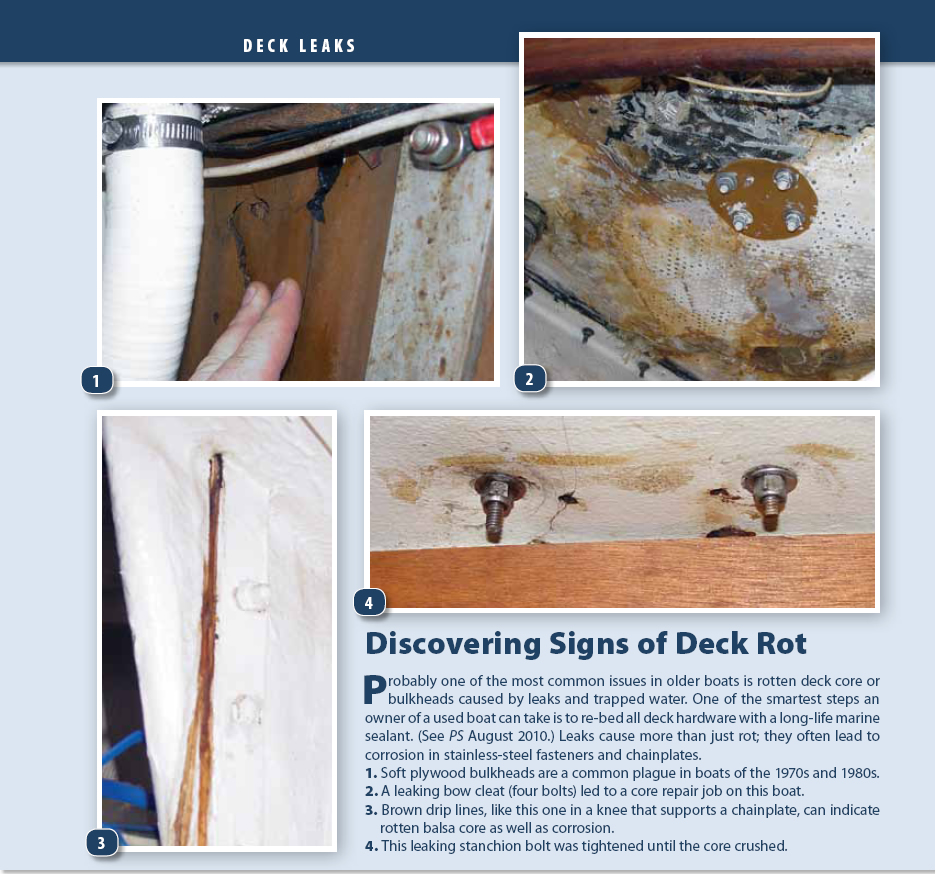

Moisture intrusion into cored decking is typically caused by a combination of failed caulking and improper installation of deck-mounted hardware (cleats, lifeline stanchions, winches, etc.). Any penetration into a cored panel must be properly sealed to prevent water entry and the damage it can cause.

The first step (literally) in finding deck problems can be as simple as walking on the suspicious spots. Soft spots, oil-canning (flexing) or even water squishing from deck fittings are all indicators of a potentially expensive repair. Drips and brownish stains belowdecks are also common signs of water-soaked decks and rotting core.

Sound out the decks by tapping them with a small, plastic-headed hammer or the end of screwdriver handle. Sharp, crisp sounds while tapping are what you want, while dull thuds can be an indication of delamination. Moisture meters are also a helpful tool for sniffing out soggy decks—we reviewed our favorites here. Make sure to check out the updated moisture meter recommendations from our knowledgable commenters there as well.

Repair options are based on the core’s condition, which is determined by taking a core sample (ideally by drilling a small hole in an inconspicuous place from the inside) and looking for moisture or rot. If the coring is rotten or damaged, it must be replaced. If wet, but not damaged and there is no delamination, attempts to dry out the core can be made. Just keep in mind that it is very difficult to remove all water and that any remaining moisture will likely cause future problems. Core replacement is the only sure cure.

Bottom line: While repair costs will be directly related to the size of the delaminated area, even a minor core replacement is a time-consuming project. If faced with a large amount of deck repair, move on to the next boat or be prepared to expend a significant amount of time, money, and effort to make it right.

STANDING RIGGING

Most sailors immediately think wire when they hear the term standing rigging, but that’s only one part of the story. Your pre-survey inspection should encompass several different components, from chainplates and turnbuckles to cotter pins and terminal ends. Here are three primary standing rigging components along with possible issues to watch out for.

Wire: Broken yarns or strands (aka fishhooks) are a clear indication that rigging wire is nearing the end of its service life, even if the other strands appear good. You can check for broken strands by wrapping toilet paper around the wire and carefully running it up and down while looking for snags or shredding of the paper.

Nicks and scratches that affect multiple strands or one strand deeply should also be noted as possible cause for replacement, as should kinks, flat spots, proud strands and corrosion, particularly where the wire enters a swage fitting.

Floppy shrouds or stays should also be inspected to determine the cause of the looseness, which can indicate anything from a much-needed rig tune-up to a failed mast step.

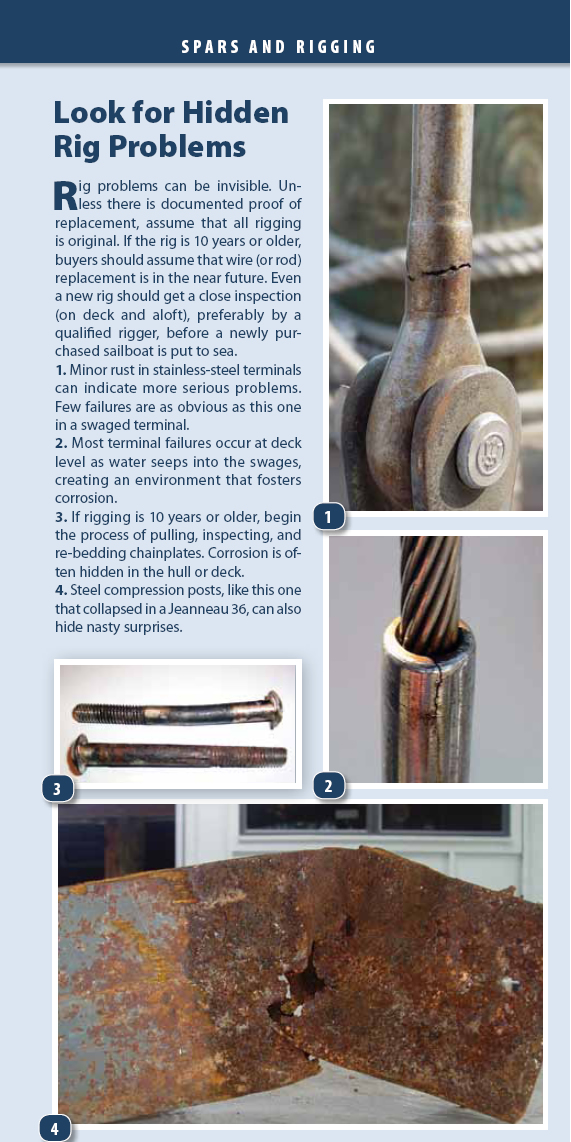

Terminal fittings: Of the various wire terminal fittings found on sailboats, swage fittings are the most common source of terminal failures.

Each should be checked carefully for signs of fatigue, proud strands (a common indication of broken strands in the swage), cracks and corrosion. A small, handheld magnifying glass can be very helpful during this inspection. Pay close attention to lower terminals, which are particularly susceptible to corrosion as a result of salt-laden water running down the wire and inside the fitting.

Bent or banana-shaped fittings (the result of improper compression of the fitting onto the wire) are also items of concern that will need to be addressed.

Chainplates: Chainplates should be checked carefully for issues such as movement, rust, cracks, deformation of the clevis pin hole and improper lead angle. Chainplates that penetrate the deck will often leak (due to movement and/or caulking failure), and the damage this causes, both to the interior of the vessel and the chainplate itself, can be significant.

Where chainplates are bolted to a bulkhead or other interior structure, look for discoloration, delamination and rot due to water intrusion. Chainplates can also be compromised due to crevice corrosion, even though the metal above and below the deck appears to be in excellent condition. Crevice corrosion occurs when stainless steel is continually exposed to stagnant, anaerobic water, such as that found in a saturated wood or cored deck. This is one reason why chainplates that are glassed in or otherwise inaccessible for routine inspection are undesirable.

Bottom line: While the life expectancy of wire rigging is determined by a myriad of factors (where the vessel is located, type of stainless, amount of use, etc.), the general rule of thumb is that it should be replaced every eight to ten years, sooner if extenuating circumstances such as offshore passages, extended cruising, racing, etc, are in the mix. While an owner may offer assurances or hazy recollections of rigging replacement, unless these improvements are properly documented, the best policy is to assume the rigging is original and plan your purchase strategy accordingly.

BLISTERS

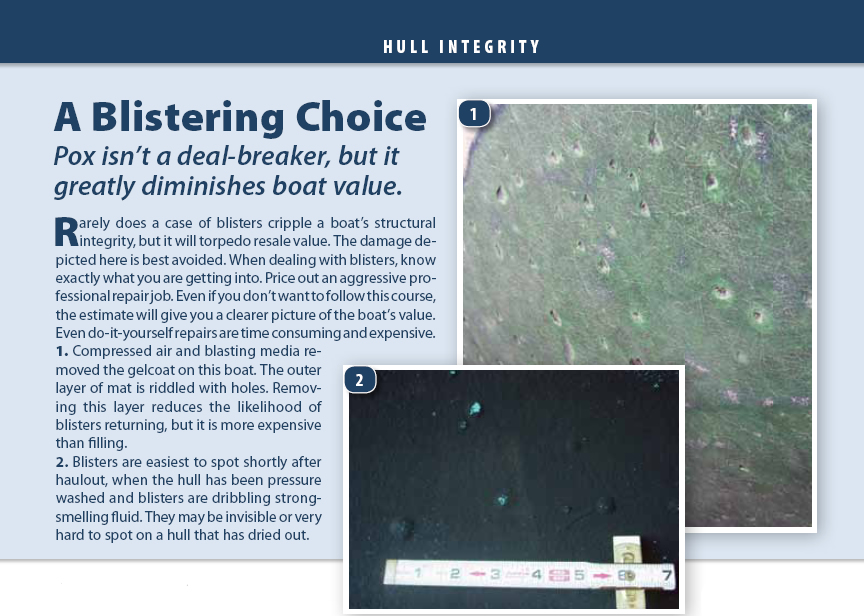

While steel hulls rust and wood hulls rot, blisters are what make a fiberglass boat owner’s hair stand on end. The Cliffs Notes version of how blisters form is simple: Water-soluble chemicals inside the laminate exert an osmotic pull on water molecules outside the hull, drawing them through the gelcoat. Once inside, the water molecules and soluble chemicals join to create a solution with larger molecules that are unable to pass back though the gelcoat. As water molecules continue to enter, pressure increases to the point that the gelcoat is pushed outward, forming a blister.

Some makes and models seem to be more susceptible to blistering than others (presumably due to factors ranging from resins used to layup schedules), but all fiberglass boats are at some risk. Location also plays a factor in some cases (i.e. relocating a vessel from cool to tropical waters, fresh to salt, etc).

The best time to spot blisters is just after the boat is hauled, preferably after the hull has been power washed and is still wet. Blisters can depressurize in a matter of hours once the vessel is hauled (minutes in some cases), making them all but impossible to spot (something to consider if inspecting a boat thats been hauled for a while).

Blisters will typically appear as circular bumps or dome-like protrusions while sighting along the hull. Sometimes water trapped between the bottom paint and gelcoat forms bumps that can be mistaken for blisters. With the owners permission, try pressing a suspected blister with a rubber gloved finger (wear goggles, as they can be under considerable pressure). If the fluid that comes out has a chemical smell, chances are it’s a blister.

Although hull blisters are often viewed with much dread, finding one or two blisters on an older vessel is no more serious than the occasional gouge to the hull. In these cases, spot treatment of individual blisters as they occur (grinding out to good material, barrier coating, and filling in and fairing with a suitable epoxy mixture) will normally suffice.

Far worse is the dreaded pimple rash or boat pox, where the entire bottom is covered with hundreds or thousands of blisters. Repairs in this case can involve removal of the entire gelcoat and the outermost skin-out mat to reach good laminate, then adding additional laminate to return the hull to original strength. It’s an expensive repair that many yards will gladly perform, but rarely guarantee will prevent future blister formation.

Bottom line: Although rarely structurally significant, blisters may very well have a negative impact on a vessels resale value, depending on the knowledge and perceptions of a potential buyer.

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS

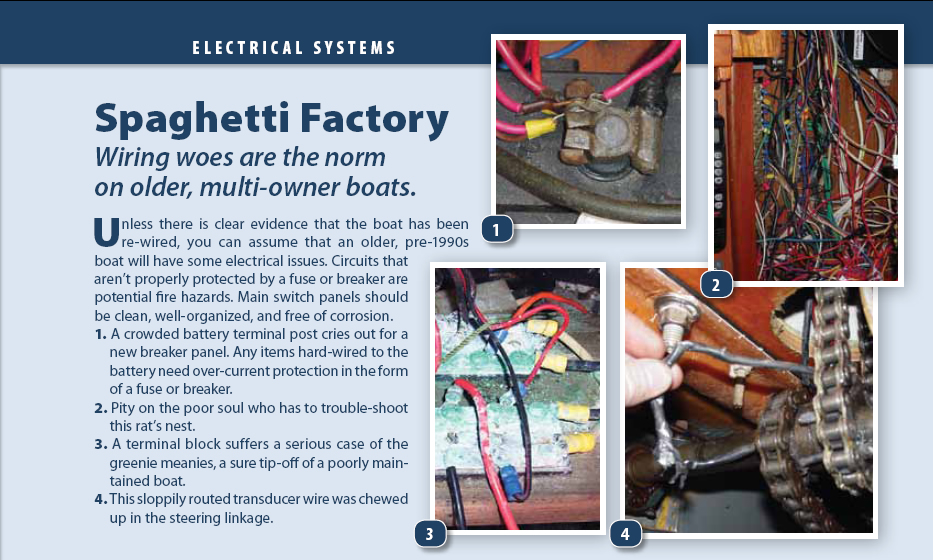

After years of additions, removals, misguided MacGyver-like installations, and overall abuse, probably no other system harbors greater potential for starting a fire on a used boat than the electrical system. This is just one reason both DC and AC systems deserve a thorough inspection.

Start with the batteries, which should be located in liquid tight / acid-proof containers (to contain electrolyte spills) and secured against movement (no more than one inch in any direction). Be on the lookout for equipment hard-wired without any fuse directly to the battery (a potential fire hazard) as well as crowded post syndrome (more than four wires connected to a single battery post).

Verify AC wiring is multi-strand, marine grade wire, not residential style, solid strand wire (aka ROMEX). Solid wire is not recommended for use onboard, as it is susceptible to breakage due to vibration. Your inspection should also verify that AC outlets located in the galley, head, machinery spaces, and on all weather decks are protected with ground-fault circuit interrupt (GFCI), another important safety requirement.

Check the condition of wire runs for both AC and DC systems. They should be neat, well organized and labeled. Problems include unsupported wires, dead ends (cut wires no longer in use), corrosion and lack of chafe protection (especially where wires pass through a bulkhead).

You’ll also want to keep an eye out for electrical tape joints and household twist-on type connectors, two sure signs that a novice has been doing a little weekend electrical work.

Bottom line: If the electrical systems are maxed out or rife with problems, play it safe by getting an estimate to make it right from a competent marine electrician before negotiating with the owner.

CONCLUSION

The more you know about potential problems and how to spot them, the more comfortable and productive your boat-buying experience will be. While the above inspection list can’t replace the practiced eye of a professional marine surveyor, it can help the average person make an informed decision on whether to pass or pursue the purchase of that potential dream boat.

You made a great point when you said that I should be on the lookout for any boats with some amateurishly fixed wiring. What with how old some used boats can be someone may have thought it better to fix old electrical components themselves rather than hire a professional which could be a potential hazard. I’m buying a boat for our family trips, and since kids will often be on board I wouldn’t want any wiring to stick out and potentially harm them or even worse, start a fire on the boat. Hopefully, I can find a good dealer that will provide me with quality used boats for sale where I won’t have to worry about matters like that.

Thanks for the informative article, Darrell.