The origin of the magnificent machine called a winch is obscure. It ranks almost as high as the lever, which can provide unlimited mechanical advantage and is probably the greatest of man’s tools.

The historians of engineering consider the six basic machines to be the screw, the wheel, the wedge, the lever, the inclined plane, and the pulley. A winch combines several of them in a compact package.

Egyptians, who were keen on pyramids, may have used windlasses, horizontal barrels (or logs), to wind up lines and drag stones on rollers up their inclined planes. Much later, someone tired of killing slaves when they lost their grip on the cranks (levers), invented the pawl, and the windlass became a ratchet wheel—which is what the sailboat winch is, a lever that concentrates and controls movement.

Someone turned the drum vertical, and the winch as we know it was born.

Larger-geared winches had their origin in the Renaissance (the 1300s through the 1500s), when Leonardo da Vinci was doodling up some marvelous stuff. But it was the conversion from steam power (with beautiful leather belts to run the power around the sweatshop) to electric power that spurred the science of gearing, which epitomizes the Industrial Revolution beginning in England between the 18th and 19th centuries. Electric motors demanded gears, as do more powerful winches with more than one speed.

What we tested

For this round of testing, Practical Sailor elected to use two-speed, self-tailing winches in the very popular No. 30 size. The size designation generally refers to the lowest (most powerful) power ratio.

Not included in this test are non-self tailing winches. They’re still out there on thousands of sailboats. And you can still buy them; marine consignment shops are clogged with them, at bargain prices.

Also not included in this test—but worth a bit of discussion because of their wide-ranging utility—are small, single-speed winches either with a handle, or simple snubbing winches. You’d not see either on Luca Bassani’s huge Wallypaloozas that race in Sardinian waters for the Rolex Cup. Such boats used to be called “Maxis,” but being much larger, are modern shades of Rainbow, the Dodge family’s Delphine, and Sea Cloud, which was only slightly longer than her cereal queen owner’s name: Marjorie Merriweather Post Close Hutton Davies May. (Bassini’s boats were featured in the February issue of Fortune magazine.)

Single-speed winches and snubbers are invaluable on small boats, for halyards, jib sheets, spinnaker sheets, reefing gear, vangs, etc. They are handy, too, for many tasks aboard larger boats.

Small winches that do not come with self-tailing mechanisms are said to have a gear ratio of 1:1, which is direct drive (one full turn of the handle takes in one drum circumference worth of line). The only power advantage is that provided by the drum diameter and winch handle. (The power ratio is the length of the handle divided by the radius of the drum.) It’s simple leverage, with two sets of pawls, one to restrain the drum, the other to permit the handle to ratchet freely. On a small boat, the single-digit power ratio provided by the handle often is ample for sheets. Non-geared winches take in line rapidly and often are used for halyards on larger boats.

Snubbing winches, which do not accept a handle, turn in one direction only. They need only a single set of ratchet pawls. If enough wraps are applied, snubbing winches give the user time to get a new grip or to simply hold the line lightly while friction between the drum and the line takes much of the load. Simple and trouble-free, snubbers are of great value when the line load is no more than one’s weight or pulling strength. They are a good adjunct to the old practice of “sweating up” a halyard by the “heave and hold” method of pulling hard on the line perpendicular to the mast with one hand while grabbing slack on the winch with the other.

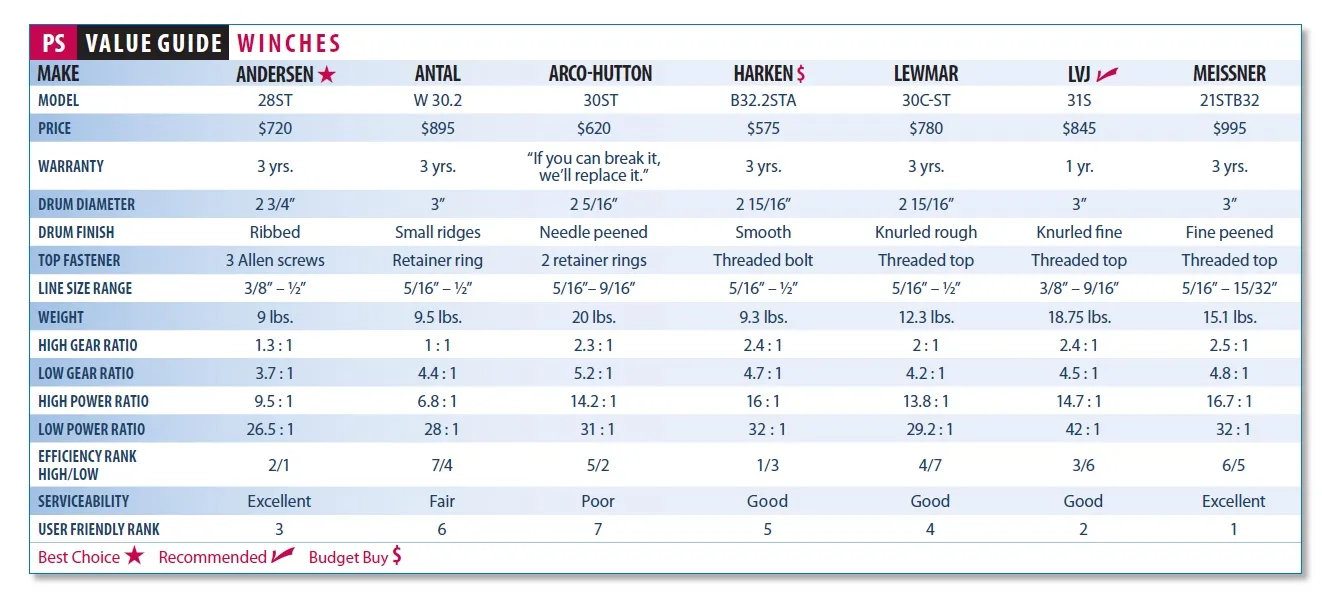

The seven winches selected for this Practical Sailor test are the Andersen (Danish), Antal (Italian); Arco-Hutton (Australian), Harken (which manufactures in both Italy and the United States), the Lewmar (British), and two Dutch winches, the LVJ and the Meissner, one of the biggest winch makers in the world. Unsuccessful attempts were made to include winches by Enkes, a Dutch company whose winches often are seen on European boats, and Nautos (distinguishable by its offset axle), a Brazilian company that has been making marine gear for the last seven or eight years without gaining much of a foothold in the United States.

Although racing sailors often want the lightest possible equipment and black anodized winch drums have been “in” for years, the weight difference between aluminum and chromed-bronze models is only about 25 percent; that’s because under the drum they’re mostly all bronze and hardened steel—except for the Andersens, which have stainless axles and other internal parts. Anodized aluminum gets shabby looking quicker and does not wear as well as chrome (which will wear away in time, too). Neither is as good as stainless. Bronze is long lasting, but if you want it to look good, you should buy stock in a metal polish company.

The finish on that portion of the drum that engages the line differs, too. The finishes used are noted on the chart above. Andersen’s ribs and Harken’s smooth aluminum drums are easiest on the line; Arco-Hutton’s needle peening probably is the toughest on line.

Most of these winch makers have extensive lines in aluminum, chrome, and bronze. Antal, for instance, has a special lightweight series that is fairly new to the market.

How we tested

These winches all are first-class gear that tend to defy being compared or judged. They’re just different. With a minimum of cleaning and lubricating, they last virtually forever. The exception might be the winches on big racing boats, the kind whose machismo crewmen like to use 8-inch handles to prove they’ve been eating lots of kreplach. A short handle is faster, of course, but it tends to partially defeat the winch’s stated power ratio, which is based on standard 10-inch handles. There are available 12-inch handles for those whose winches lack the needed power. If more power is needed, another option—albeit an expensive one—is to install more powerful winches.

Besides closely examining these seven winches (especially the self-tailing mechanism) and using them for many hours, the test procedure was designed to determine which winches deliver best on their promised power ratios. Another way to put it is: How much of its power ratio does each winch lose in useless friction?

To that end, the bench was set up with loops of half-inch shock cord, to provide an elastic load, gathered in a stout stainless ring that was shackled to a recently calibrated Dillon dynamometer, which has a handy “max” needle.

A length of New England Rope’s 3/8-inch Sta-Set all-dacron braid ran from the other end of the dynamometer to the winches, which were mounted on a pair of 3-foot lengths of 2-by-10-inch planks. The planks each accommodated three winches (the Meissner was a late arrival and was tested separately). When in use, a plank was secured to the bench with a 2-by-4-inch horizontal “stop” and a steel U-clamp. The winches were positioned to give them the recommended 1- to 20-degree angle at which the line enters the bottom of the winch to minimize overrides. Following the mounting instructions, the output gear of the winch (the one that engages the teeth at the bottom edge of the drum) was placed perpendicular and adjacent to the point where the line first enters the drum.

Instead of using a standard 10-inch winch handle, PS substituted a Sears Craftsman 3/8-inch drive torque wrench with a 5/8-inch adaptor fitting that just happens to fit the internationally accepted star socket on winches.

The arrangement was assembled to simulate headsail loads. In every case, three turns (the minimum recommended by any winch maker) were taken on the drum before being seated in the self-tailing groove.

With the torque wrench, any reasonable load (in foot-pounds) can be applied to the winch. For this test, 10 pounds, a very comfortable load, was used, and the high and low gears of the winches delivered loads ranging from 24 pounds (which imitates moderate air loads on a genoa) to 260 pounds (which could be fairly heavy air with a working jib). For anyone other than racing boats, loads beyond those would call for a headsail change. Ten “run-ups” were made with each winch in each gear, unless the yield on the dynamometer proved very stable at lesser numbers.

Finally, arithmetic adjustments were made in the calculations because of the long torque wrench handle. The handle is 131/2 inches from the center of the socket to a pin in the wobble handle. The seemingly slight increase in the length of the torque wrench over a standard handle provides more than 33 percent more power.

Finally, the loads actually achieved were converted to a percentage of the manufacturers’ stated claims. It was not expected that the stated claims, which are theoretical, would be “proved” because any winch loses much of its advantage to friction. The loss with these seven winches was about 50 percent, except for the very efficient Andersen.

Practical Sailor’s figures in the efficiency row (see chart at end of article) indicate the rank (shown as the Andersen’s “2/1,” etc.), in both high and low gears, of each winch as determined by the percentage of the theoretical loads each winch recorded in the actual testing.

For instance, the Harken is ranked first in high gear because, with 10 pounds on the torque wrench, it delivered a 140-pound load, 63 percent of the 220 pounds it theoretically should have done; the Andersen was close behind.

In low gear, the Andersen delivered 300 pounds, 90 percent of the 333 pounds it theoretically should have done; the Arco-Hutton was second best.

After the 10-pound tests were completed, some additional higher load tests were done to introduce high-output figures to include in PS’s considerations. The high-load testing produced no surprises.

Because this was not (and could not) be a precision procedure, the test findings can be said only to indicate which winch provided the greatest advantages, in both high and low gears, and which were easiest to use.

The “easiest-to-use” considerations had mostly to do with how easy it was to place three wraps on the drum, catch the self-tailing guide and sock the bitter end home in the self-tailing groove…along with how easy it was to disengage the self-tailing to ease the line. It might rightly be said that most anything done repeatedly becomes easy. However, winches with self-tailing arms that protrude as little as possible and that have big fixed grooves are easier than those with protruding arms and small spring-loaded self-tailing grooves. For instance, with those winches with big, fixed grooves—the Andersen, LVJ, and Meissner—the line is easy to guide into place; it’s done easily with one hand. With the Antal, Harken, and Lewmar, which have small guide arms and small spring-loaded slots, it often takes two hands.

Also contributing to the rankings was serviceability. Those winches that open up via simple threads (Andersen, Harken, Lewmar, LVJ and Meissner) are preferable to those (Antal and Arco) that still depend on very difficult to manage—but easy to lose—retainer rings.

Conclusions

When selecting winches for your boat, the important considerations are what kind of sailing you do, in what weather, and how quickly you change sails to comfortably match the winds. If you’re a racing sailor who presses hard, winches need to have ample power to handle loads that would not be imposed by a conservative cruising sailor who changes or reefs sails to avoid unnecessary strains on sails or rigging.

Note in the chart the great differences in the gear ratios of the seven winches. The Andersen and Antal have high-gear ratios that would quickly bring in the jib sheet. With the Harken and Meissner, the high-gear ratio might mean that you would want to overhand the slack before resorting to the winch handle.

On the other hand, for final trimming in strong wind, the low gear power of the LVJ (42:1) and Harken (32:1) would make life somewhat more comfortable than the Andersen’s 26.5:1 ratio. (As tested, the Andersen’s efficiency makes up for much of that disadvantage.)

That’s why the Andersen, made mostly of stainless steel, is Practical Sailor’s choice as the best of the seven. Its ribbed drum is famously gentle on lines, it’s easy to operate and service, and it’s long-lasting metal is easiest to keep looking good.

For low-gear power, the standouts are Harken (famous for good bearings) and the massively LVJ and Meissner.

In between, the Lewmar (which is very nicely engineered) and the Antal (which is beautifully machined and polished) are fine examples of their makers’ products.

Last but surely not least, if you want a brute of a winch, the Arco-Hutton from Australia won’t disappoint you, other than that it’s difficult to service, primarily because you must cope with not one but two difficult retainer rings.

Contacts

• Andersen, 800/535-6009, www.scandvik.com

• Antal, 800/222-7712, www.euromarinetrading.com

• Arco-Hutton, +61 2/9623-2448, www.arco-winches.com

• Harken, 262/691-3320, www.harken.com

• Lewmar, 203/458-6200, www.lewmar.com

• LVJ, 860/599-0800, www.lvjwinchesusa.com

• Meissner, 866/577-5505, www.RWrope.com

I looked but didn’t find any reviews of electric genoa winches. If there are PS article(s), perhaps you can point me to them? Are there any soon to be published articles on the subject? I have a masthead 36′ C&C 110 with Harken 46 2 speed winches and am looking at the Harken 46.2 STEA and the Lewmar 45 (49545203) as replacements. Do you have any observations/comparisons of Lewmar’s electric load sensing speed system vs Harken’s more conventional 2 speed design? And as a possible an alternative approach, what about the Pontos/Karver KPW 4 speed manual winch, might it be a reasonable alternative to an electric?